BBG Watch History

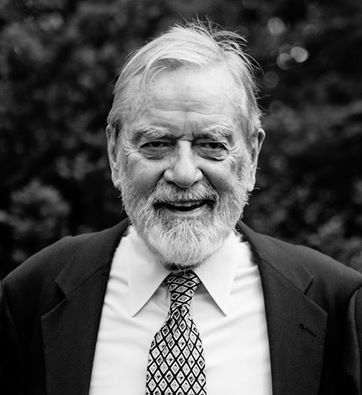

McKinney Russell (1929-2016). Family courtesy photo.

McKinney Russell (1929-2016) – diplomat, Radio Liberty reporter, Voice of America manager

By Ted Lipien

Men and women of extraordinary abilities helped the United States win the Cold War. One of the most significant figures of that period in U.S. public diplomacy and international broadcasting history was McKinney Russell. In 1959 he covered for Radio Liberty’s (RL) broadcasts to the Soviet Union the two-week trip to the United States by the then Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev. He was in charge of Voice of America (VOA) radio broadcasts to the USSR during the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, and was one of the United States Information Agency’s (USIA) most admired career diplomats.

Before his diplomatic career, which lasted from 1962 until 1994, McKinney Russell had served in the 1950s as Radio Liberty translator/reporter/editor/newsroom manager in the 1950s. Later, as a Foreign Service Officer (FSO), he was assigned to manage Voice of America European and USSR broadcasts in the 1960s. He served as Cultural Affairs Officer (CAO) and Public Affairs Officer (PAO) in Moscow in the 1970s, PAO in Beijing during the Tiananmen Square massacre, and was a university professor. McKinney Russell passed away on February 17, 2016.

I had never met McKinney Russell, but when I joined the Voice of America in 1973 as a young VOA Polish Service broadcaster, I heard his name mentioned frequently in the VOA building in Washington, DC. Even then, he was already a legend among VOA’s journalists working for foreign language services. While Voice of America saw itself primarily as a news organization, he was an FSO who was genuinely liked by many VOA broadcasters and made a positive difference in VOA broadcasts to the Soviet Union.

After the news of his death, I reached out to a few former VOA and USIA colleagues who knew McKinney Russell. Former VOA Russian Service Director Marina Oeltjen wrote:

MARINA OELTJEN: McKinney Russell was a true class act, one of the best the Foreign Service had to offer. He also spoke excellent Russian. He was admired and respected and championed journalistic excellence.

Ludmila Obolensky-Flam, who had met McKinney Russell even before he joined Radio Liberty, wrote:

LUDMILA OBOLENSKY-FLAM: I first met him, would you believe it, in 1952 or 1953! He would occasionally come to Munich and call on us Natasha (Clarkson) and myself at the VOA European Service. I remember how impressed we were with his knowledge of Russian. At that time the young McKinney was working as an administrator at a house for Soviet Army defectors somewhere near Frankfurt in the American zone. We used to speculate what a culture shock it must have been for a recent Harvard graduate to come into close contact with a bunch of some pretty tough guys, whose defection from the Soviet zone was not necessarily motived by political reasons.

Somewhat later, my first husband Velarian Obolensky, formerly from BBC, who became head of Radio Liberty’s News, told me he had a fantastic new staffer, a talented and energetic linguist, RL’s first news correspondent. This, of course was McKinney Russell. In those early Munich days we became close friends with him and his wife Lydie, members of our group of young and forward-looking couples. While those days could not be replicated, we have subsequently never lost sight of each other.

After my first husband’s death, and with with McKinney’s various overseas USIA assignments, which so deservedly propelled his career, I saw less of him. That is until his last Washington tour, when I myself was still at VOA, and later into retirement, whether dealing with McKinney professionally or meeting him socially, my husband Eli Flam and I have always kept a very high regard for him and found his company both stimulating and enjoyable.

Ludmila Obolensky-Flam

Former VOA Russian broadcaster Marie Ciliberti who had worked on the Russian version of Willis Connover’s famous jazz program whose broadcast to the Soviet Union was championed by McKinney Russell, wrote:

MARIE CILIBERTI: McKinney Russell was Chief of the VOA Russian Service during the height of the Cold War. A roll-up-the-sleeves type of VOA Branch Chief and manager, he impressed many in VOA Russian with his superb knowledge of the language and the culture. A rare linguistic talent, he was also fluent in German, Portuguese and Mandarin (and probably other languages as well). Gifted in so many spheres, he was deservedly recognized for his accomplishments with the rank of Career Minister in the U.S. Information Agency. Down-to-earth, charming, a great raconteur, a true Renaissance Man, McKinney Russell was a credit to his Agency and his country. It was a privilege to have worked with him. Requiescat in Pace, Cold War Warrior.

Former VOA Russian Service broadcaster Irina Burgener wrote:

IRINA BURGENER: McKinney Russell hired me to work at VOA. We started our conversation in English and mid sentence we switched to Russian, he was smooth as silk. He put a very nervous grad student at ease and made her feel important and needed. Never met a gentleman like him, he was wonderful.

Former USIA Public Affairs Officer John Brown wrote:

JOHN BROWN: He was a remarkable diplomat — and extraordinary linguist.

McKinney Russell was born in 1929 in New York City. His father was a newspaper man for the Brooklyn Eagle. Both of his parents had moved to New York from the South. A 1950 Yale graduate in Russian area studies, McKinney Russell spoke fluent Russian in addition to several other languages, including Polish.

After graduation from Yale, McKinney Russell had served for two years in the U.S. Army in Europe and later worked for an American-funded non-governmental organization, American Friends of Russian Freedom, which provided humanitarian assistance to Russian refugees in Germany. He was a phenomenally talented linguist. When he spoke German, Germans mistook him for one of their own. Because sometimes he had to get errant Russian refugee alcoholics and petty criminals out of German jails, his Radio Liberty colleague James Critchlow recalled that Russell also had an enviable command of slang used by Russian criminal elements.

In 1955 Russell got a job at Radio Liberty in Munich as Head of Translations Office and later worked as RL’s Special Events Correspondent, Chief Correspondent, and finally Deputy Head of News. While in Germany, he took and passed the Foreign Service exam. Rather than opting for a traditional diplomatic career at the State Department, in 1962 he chose the United States Information Agency (USIA), a public diplomacy arm of U.S. diplomatic service which at that time also included the Voice of America. In a 1997 interview, he said that “the entry into the White House in 1961 by John F. Kennedy and his designation of Edward R. Murrow as the Director of USIA were both important factors in leading me to want to work in the Agency.”

After his first assignment abroad as Assistant Information Officer to Leopoldville, now Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, he returned to Washington in 1965 and became Policy Officer for the African Area of USIA. At that time, he was also involved in his position at USIA with the VOA broadcasts in English, French, Portuguese, Swahili and Hausa. From 1967 to 1969, as a USIA Foreign Service officer, McKinney Russell was put in charge of Voice of America broadcasts in Russian, Ukrainian, Georgian, and Armenian.

While some non-USIA managers and VOA English service reporters objected to USIA officers occupying key VOA executive positions, many foreign language broadcasters like myself had much more in common with these public diplomacy FSOs and greatly appreciated their presence. These U.S. diplomats spoke foreign languages, could engage in long discussions about foreign cultures, were conversant with more obscure foreign policy issues relating to our target region and were generally perceived by VOA language service staff as better managers. There were also a few longtime VOA editors who had been educated in Europe, knew the target area well and had good relations with language services. The combination of the two worked well. During that time, USIA had been a pool of great talent and expertise. This was lost along with high recruitment standards, prestige and influence abroad, when the agency was abolished in 1999, with VOA and other media entities going to the newly-formed Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), and U.S. public diplomacy going to the State Department. After it became an independent agency, BBG and VOA within it were never able to attract anywhere near the kind of superior talent that VOA had under USIA, at that time either through assignments from USIA or through its own then much more rigorous and competitive recruitment.

This is how McKinney Russell described his 1967-1969 FSO assignment at the Voice of America in a copyrighted 1997 interview with G. Lewis Schmidt for the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training’s (ADST) Foreign Affairs Oral History Project.

This is how McKinney Russell described his 1967-1969 FSO assignment at the Voice of America in a copyrighted 1997 interview with G. Lewis Schmidt for the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training’s (ADST) Foreign Affairs Oral History Project.

MCKINNEY RUSSELL: My earlier experience at Radio Liberty, where I was Deputy News Director when I left, prepared me for this job, as did my knowledge of Russian. Those 2 years were, I have to say, singularly demanding and complicated. There were 120 people in the division which had been, when I arrived, part of the European Division of the VOA. We all felt rather uncomfortable under that umbrella, since the problems we faced were so different, and I began early on working for the creation of a separate division. After 6 or 8 months, that was successful, and the USSR Division was created.

The non-Russian services were much smaller-the Georgian and Armenian services had only 5 or 6 members, the Ukrainian might have had 10-but the Russian had some 85 or 90…they were broadcasting in Russian 17 or 18 hours a day. There was a challenging range of complexities in that job. One, of course, was that of creating interesting programs every day for the audience, and it was an audience with which, at that time, I had never had any contact. I had never been to the Soviet Union when I took over this job in August 1967. I had hoped that soon after the move, say within 6 months, I would make a trip there to gain on the ground some direct sense of the audience. I made that trip in December 1967 to all four of the areas, Russia, Ukraine, Armenia and Georgia to which we were broadcasting.

The policy issues were very complicated, among other things, because there were political differences within the services, often between people who had divergent backgrounds and saw things very differently. In the Russian Service, for example, there were those who had come out after the 1917 Revolution who were men and women already in their sixties. Then there were those who had remained in the West during or after the War. And there were yet others, most of whom had come out in the 1960s. These different generations had very varied different experiences and perspectives and often they were at loggerheads with each other. There was a lot of mediation and keeping people apart that came with heading up that broadcasting unit at the VOA.

The most striking single event during my tenure was the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. When I joined the VOA, there had been no jamming by Soviet jammers since 1962. It was during the invasion, with the move of Soviet troops into Czechoslovakia, that jamming was reinstated and again created the problems of getting through that interference.

The mid-‘60s were in general a period of Americanization of the VOA broadcasts to the USSR. My immediate predecessor, Terry Catherman, a particularly energetic and effective officer, had spent 3 years there, and had made it his policy to bring on many young Americans whose Russian may not have been perfect but who had a much brighter and fresher approach to broadcasting. He had introduced programs of popular music with the disc jockey work being done by young Americans rather than Russian emigres. Terry’s predecessor had been a former Soviet general who had defected in 1934 in Athens, a man named Alexander Barmine. He was a very conscientious, very committed broadcaster, but also a very authoritarian figure, and one who did not think that young Americans whose grammar in using the Russian language that was not perfect should be on the air. Well, Catherman had made a new approach stick during his tenure, and I was very pleased to continue in the same track that he had initiated.

I was scheduled to go as Cultural Affairs Officer to Moscow in 1968 after one year in the Voice of America, but that transfer was postponed for a year until 1969. So I had 2 full years in the VOA, and still have friends from that period. There is a special kind of esprit de corps among Voice people that we foreign service officers came to appreciate very much. (Copyright 1998 ADST.)

In the same 1997 interview for the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, McKinney Russell also described his earlier career at Radio Liberty before he joined the USIA diplomatic service.

In the same 1997 interview for the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, McKinney Russell also described his earlier career at Radio Liberty before he joined the USIA diplomatic service.

MCKINNEY RUSSELL: In the spring of 1955, a job as Head of Translation at Radio Liberty opened. I was accepted for it and moved to Munich in my old green Opel car in April 1955. Of course, both stations were funded by the Central Intelligence Agency, although no one told me that for 3 or 4 years. The people ultimately in charge, very few of whom knew any Russian, had no idea of what the broadcasts were actually saying. Thus a number of translations had to be made for their benefit of parts of the program every day. Since the translators were all non-native English speakers, the head of the translation section had to do the editing to make sure that the results actually roughly approximated the English language.

I had that job for about 6 or 7 months and then progressively moved up within the organization until I left it in October 1962. I became Special Events Correspondent, then Chief Correspondent, then Deputy Head of News. It proved to be a very interesting professional life, calling for a good deal of travel in Europe. I was often in Brussels or Paris and made half a dozen reporting trips to Scandinavia. The point was to inform listeners in the Soviet Union through feature programs which were then translated into Russian and the other languages. We reported on how free trade unions work in Western Europe; what the living conditions were for people in Finland right next to the Soviet Union; how Swedish elections took place in the glare of sharp competition between competing parties, the overall idea being to provide an alternative picture of what life could be in free countries, and not only in the United States. There were broadcasters from New York and Washington, but the radio station broadcast, as did Radio Free Europe, not as an American station like VOA but as voices of their own peoples.

In 1959, I was on home leave from Munich and had the opportunity of covering the two-week trip to the United States by the then leader of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev. I traveled with him from Washington to New York, and to the West Coast, up to San Francisco, to the farm in Iowa, and so on. The principal long-term event in my life during those years was meeting the woman whom I married and to whom I have been married ever since. In February of 1957, after I had been in Munich almost 2 years, I met at a dinner party with colleagues from the Radio Liberty, a young woman of French culture, Italian citizenship, and great charm. She had grown up in Tunisia and was visiting friends in Munich. Her name was Stella Boccara. We decided rather quickly that we went very well together and were married not too long thereafter. Our first son McKinney Junior, was born in 1959, in Munich, and our second child, daughter, Valerie, was born in 1961, also in Munich.

(Copyright 1998 ADST. For more of the 1997 ADST interview with McKinney Russell see: Foreign Affairs Oral History Collection, Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, Arlington, VA, www.adst.org. Direct link: http://www.adst.org/OH%20TOCs/Russell,%20McKinney.toc.pdf)

Richard H. Cummings, Former Director of Security at Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) and the author of “The Dangerous History of American Broadcasting in Europe, 1950–1989” and “Radio Free Europe’s ‘Crusade for Freedom’: Rallying Americans Behind Cold War Broadcasting, 1950–1960,” wrote an article about McKinney Russell’s work at Radio Liberty, “McKinney Russell (1929-2016), RIP.” For more fascinating information about Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty during the Cold War see Richard Cummings’ Cold War Radio Vignettes Blog.

After a long and successful post-Radio Liberty career at USIA, McKinney Russell retired in 1994. He spent the last year teaching at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy as Diplomat in Residence and Professor. To my great regret, he never became a PAO in Warsaw. This was due to a new limit for length of time overseas, which led to him being assigned to a USIA position in Washington rather than in Warsaw.

Working on assignment from USIA at the Voice of America seemed to have left a strong impression on McKinney Russell. He made many friends at VOA. In his 1997 interview, he mentioned several VOA personalities, including one extraordinarily talented now former Voice of America Russian Service broadcaster Mary Patzer.

“There is a marvelous broadcaster at the Voice of America named Mary Patzer, whose Russian was virtually native, who got her start as an exhibit guide back in the ‘60s.” These were USIA-organized educational, cultural or technological exhibits which the Soviet regime allowed on tours in the Soviet Union after much negotiating, some of which was done by McKinney Russell. Not just Mary Patzer, but a few other American exhibit guides who had learned Russian later ended up working for VOA’s Russian Service. McKinney Russell also mentioned in that interview “An old friend from Radio Liberty days, Francis Ronalds,[who] was VOA program manager.” It was not uncommon for RFE/RL journalists to end up at VOA and vice versa. In the VOA Polish Service I had worked with several outstanding former Radio Free Europe journalists, including Marek Swiecicki, Marek Walicki, and Waclaw Bninski. I helped Marek Łatyński get a job at the Voice of America after he had left Radio Free Europe. Marek Łatyński later returned to Radio Free Europe to become the director of its Polish Service. When Poland regained its independence, he was Poland’s ambassador to Switzerland.

There were many links between USIA and VOA, but not between USIA and Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. The two radios had a much different mission, and it all worked well. Of course, there were also problems and occasional crises, but in the end both U.S. public diplomacy and U.S. international broadcasting, split between VOA and RFE and RL, were extraordinarily successful each in its own way. In the 1997 interview, McKinney Russell alluded to some tensions between VOA broadcasters and FSOs like himself serving at VOA in executive positions on temporary assignments from USIA. Not all USIA FSOs were as good or as well liked as McKinney Russell. A few tried to censor VOA broadcasts, but then there were also others who risked their diplomatic careers to resist censorship pressures from above.

As a former journalist, McKinney Russell would not have been likely to interfere with VOA’s news. No one I spoke to at VOA has ever accused him of censorship or any editorial missteps. On the contrary, everybody praised him as being a gentleman and a superior manager. One of his successors, however, who I believe was a State Department diplomat rather than a USIA officer, ordered VOA’s Russian Service not to broadcast excerpts from Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s book. The order may have through him come from the State Department itself. Only one highly successful former VOA Russian broadcaster, whom McKinney Russell had hired, told me that like many FSOs working at VOA, he took credit for the work done by VOA’s foreign language broadcasters. The same, of course, could have been said to a much greater degree, about career VOA managers who were far more difficult to work with for foreign language service staffers. Everyone else I talked to described McKinney Russell in highly positive terms.

In my own VOA career, I never experienced any serious management problems caused by FSOs or any attempt at censorship from USIA officers. With the exception of a few VOA managers or reporters who had European education or served in Europe as news reporters, I found USIA FSOs to be not only better informed but also much easier to work with. Since the end of the 1990s, I have not seen many people of the same creativity and intellectual caliber being attracted to work for VOA or the Broadcasting Board of Governors.

While there were definitely some tensions between USIA FSOs and some career VOA broadcasters and journalists while I was still at the Voice of America, they did not affected me personally. In any case, I was then still fairly low in the organizational hierarchy, but I enjoyed having an excellent working relationship with USIA and cultivated information sources among both USIA and State Department officials. I wrote about it in my 2011 America Diplomacy article “Interweaving of Public Diplomacy and U.S. International Broadcasting.”

This is how McKinney Russell described the tensions in the USIA-VOA relationship when he was interviewed in May 1997.

MCKINNEY RUSSELL: The standard procedure in those years was that the heads of the various geographic divisions [at the Voice of America] would be foreign service officers. The head of the Near East Asia Area would be someone who had recently served there, and the result was that there was usually a close and cordial personal relationship between the Agency’s foreign service and the broadcasters. At the same time, though, in part because of the pressures that built up when broadcasters had been on the job for 10 or 12 years, 15, 18 years and had gained real expertise as broadcasters. Repeatedly there would be a foreign service officer who would move in as head of the division and this was bound to generate resentment.

A policy shift began later that saw civil servants, broadcasters with the VOA, at the head of the various division units. This must have started in the early or mid-‘70s. By now it’s become standard and there are very few, if any, foreign service officers in positions of broadcasting authority at the VOA. But despite some tensions in those years, it was, I thought, a very positive way of keeping two distinct elements of the Agency talking to

and working with each other. John Charles Daly was the head of the VOA at that time, a serious American broadcaster and well-liked quizmaster, a very open-spirited, energetic man.It was a very stimulating and interesting place to work, and I have, as I say, very fond memories of it. (Copyright 1998 ADST.)

McKinney Russell was one of many remarkable Foreign Service Officers who had made great contributions to the Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and Radio Liberation (later Radio Liberty). I’d like to mention briefly two other career diplomats, whom I also did not know personally, Ambassador Arthur Bliss Lane and William A. Buell, Jr., but who played an important role in the early history of VOA’s Polish Service. Many years after they had left their mark, I worked first as a broadcaster and subsequently as VOA Polish Service chief during the Solidarity trade union’s struggle for democracy in Poland in the 1980s. They both embodied the same outstanding Foreign Service qualities that McKinney Russell did during his career.

After he retired from the State Department in 1947 in protest against U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union, Ambassador Arthur Bliss Lane (1894-1956) worked to establish Radio Free Europe. He also helped famous anti-Nazi and anti-Communist journalist Zofia Korbonska get a job in VOA’s Polish Service which during World War II operated outside of the State Department as part of the Office of War Information (OWI). The service along with much of VOA was dominated at that time by pro-Soviet sympathizers broadcasting Soviet propaganda, which even the State Department objected to from time to time despite the U.S. and Russia being wartime allies. OWI was abolished in 1945 as a separate government office, with VOA moving to the State Department and forbidden to engage in U.S. domestic media activities, which OWI did during the war causing widespread controversy because it censored news unfavorable to the Soviet Union. Ambassador Bliss Lane was a strong critic of VOA, both during World War II and even after VOA was transferred to the State Department, but thanks to journalists like Zofia Korbonska VOA eventually became an important source of information in Poland, although never as good as Radio Free Europe’s Polish Service. In 1953, VOA was put in the United States Information Agency and remained within USIA until 1999. Under USIA and with USIA officers serving in key positions, VOA had its greatest reach and impact around the world, but particularly in Eastern Europe and in the Soviet Union.

While Ambassador Bliss Lane retired from the State Department long before USIA was created and was never directly linked with the Voice of America, some USIA FSOs like McKinney Russell who had served at VOA in the 1960s, 70s and 80s are remembered fondly by former language service employees as good managers and innovators. Another USIA FSO, William A. Buell, Jr., who died in November 2011, was a well-respected director of the Polish Service from July 1965 to July 1966, which was also before my time at VOA. Following his retirement from the Foreign Service, Buell worked as a legislative assistant to Senator Adlai E. Stevenson III and after 1977 spent ten years at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, the first two years as RFE Director in Munich and later as Senior Vice President of RFE/RL in Washington. He was one of many officials who moved back and forth between the broadcasting entities. Some like the legendary program host Patricia Gates Lynch started out as VOA broadcasters and later joined the diplomatic service. She was nominated to be U.S. Ambassador to Madagascar by President Reagan. I also worked at VOA with Ed Kulakowski who later joined USIA and assisted me in placing VOA and RFE/RL programs on stations in Eurasia.

In the late 1980s while the Voice of America was still under USIA, VOA’s Polish Service caught up with RFE’s Polish Service in the number of radio listeners in Poland, but it could never match RFE’s impact as a surrogate broadcaster. VOA’s fortunes started to decline after it was separated from USIA. The USIA was abolished as a separate agency. VOA and RFE/RL were administratively consolidated into the Broadcasting Board of Governors which was made an independent federal agency. There were no longer any public diplomacy FSOs working at the BBG. The decline of both U.S. international broadcasting and U.S. public diplomacy as a result of these changes and consolidation was predicted in 1995 with remarkable accuracy in a letter former VOA European Division Deputy Director and former VOA Newsroom editor Vello Ederma wrote to Senator Jessie Helms. Ederma was protesting Helms’ efforts in cooperation with the Bill Clinton Administration to eliminate USIA and move public diplomacy functions into the State Department.

VELLO EDERMA: Thank you for your answer to my plea not to destroy the Voice of America. Your operative answer of course is the last sentence: “However, consolidating the administrative functions for our international broadcasting ventures will allow the United States to more effectively use the resources we have available.” And you state that “the programs will be directed by the Broadcasting Board of Governors.” The first statement appears inaccurate and the second a major fallacy. I understand your intentions are budget-driven, but the fat in budgets can be trimmed without cutting the guts or junking the broadcasts.

Unfortunately, the two statements have no connection with the real world and may eventually destroy VOA.

In reality,the programs will never be “directed by the Broadcasting Board of Governors.” This group will meet a few times a year for a few hours to ratify whatever is being done. More likely, the Board will create a new bureaucracy. This will open up all kinds of “command and control” possibilities that will very likely infuriate senators like yourself, whether on philosophical or any other grounds Only this time you will have yourself to blame.

(…)

The separation of “public diplomacy” functions from traditional, secretive State Department diplomacy has served the U.S. national interest well. The ability of Americans to connect with the foreign media, educational and other open public environments without the tinge of “officialdom, propaganda or intelligence” has created a second tier of friendly relationships among peoples that the State Department has never been able to do nor is that its function. USIA officials have always had the ability to communicate more openly and freely with the public and interest groups, sowing greater confidence and trust. State officials or Foreign Service officers in the field talk to their respective government counterparts, not to the public at large.

(…)

The simple fact is that we need a credible VOA now more than ever, not a State mouthpiece. American ideals and values of freedom, democracy and the free market that we want to convey are best done by a free VOA, NOT a State mouthpiece or a CNN. The idea of “consolidating administrative functions” to “allow more effective use of resources” is wide of the mark. Reality is very different. Such consolidation of resources will destroy VOA credibility. When it happens, and it surely will, I’ll remind you of what I said in this letter.

It happened exactly as Vello Ederma had predicted. Much of what McKinney Russell had worked decades to create was destroyed with the consolidation of U.S. public diplomacy into the State Department and the creation of the Broadcasting Board of Governors. VOA ceased to be a major destination for news worldwide in the digital age. The effectiveness of both U.S. public diplomacy under the State Department and independent U.S. media outreach under the BBG were severely undermined after USIA was abolished. BBG’s influence and relevance with the political establishment in Washington is not anywhere near what USIA, and VOA with it, enjoyed before for many decades. In 2013, then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and by the way an ex officio BBG member, told a Congressional committee that the “Broadcasting Board of Governors is practically defunct in terms of its capacity to be able to tell a message around the world. So we’re abdicating the ideological arena, and we need to get back into it. We have the best values. We have the best narrative.”

But before the sad turn of events after 1999, whether at USIA or at VOA, McKinney Russell and other talented USIA officers had worked hard to advance America’s narrative. I regret that I did not have a chance to work directly with him after hearing so much about him from my older VOA and USIA colleagues and about his deep interest in Poland. But I feel privileged having worked as a VOA journalist on Poland and other East European news issues directly or indirectly with many other USIA FSOs, including both Terry Catherman and Jack Harrod whom McKinney Russell mentions in his 1997 interview, Robert Warner who hired me together with the then Polish Service Chief Marian Woznicki, Jack Jones, Ambassador Robert L. Barry, Ambassador Bob Gosende, Ambassador John D. Scanlan (another fluent Polish speaker), Len Baldyga, Hans N. Tuch, John (Jock) Shirley, John Brown, Paul Smith, Csaba Chikes, Thomas W. Simons Jr., Penn Kemble, Mark Dillen, Anne Chermak Dillen, Lisa Helling, Anna Romanski, Philip Reeker, Ambassador Anne M. Sigmund, Dell Pendergrast, Bob Coonrod, Joe Bruns, Richard A. Virden, Lawrence Plotkin, Carl Bastiani, Morris E. Jacobs, Eli Flam, Woody Demitz, Hans Holzapfel, Edward Mainland, William S. Dickson and William Hill to name just a few.

I should add that not all of my former VOA colleagues agree with me with regard to some USIA officers who had served at VOA. They may be right because my interactions with some of them were brief, while my other VOA colleagues worked with them on a daily basis, but their overall contributions and the link between VOA and USIA were highly positive, in my view. I was also in contact with many State Department officers, career and political appointees, who had served in Poland, including Ambassadors Richard T. Davies, William E. Schaufele, Jr., Francis J. Meehan John R. Davis, Jr., Thomas W. Simons, Jr., Daniel Fried, Christopher R. Hill, Victor Ashe, Lee A. Feinstein and Stephen Mull. Some of them are no longer alive. McKinney Russell was certainly among Radio Liberty’s, VOA’s, and USIA’s greatest public servants in the second half of the 20th century who helped the United States win the Cold War.

Former Polish President Lech Walesa, who unfortunately is now a target of misguided and completely unfair media accusations of alleged collaboration with the communist regime as a result of nothing more than an old communist secret police provocation, told VOA a few years ago: “Therefore, it is difficult to imagine what would have happened if it were not for the Voice of America and other sources with the help of which the true information squeezed through, which showed a different point of view, which said that we are not alone and that something is happening in the country — because our mass media did not do that.”

McKinney Russell was part of that historic effort.

McKinney Russell, thank you.

“Thanks for listening and if you see someone without a smile, give him one of yours” — former VOA English Breakfast Show program host Pat Gates

A non-denominational Memorial Service in honor of the late McKinney H. Russell will be held on Thursday, February 25, 2016 at Temple Shir Tikvah, 34 Vine Street, Winchester, MA 01890. Letters of condolence may be sent via Kyle Russell, PO Box 440263, Somerville, MA 02144.

Disclaimer: Ted Lipien, a former Voice of America acting associate director, is one of BBG Watch’s co-founders and supporters.