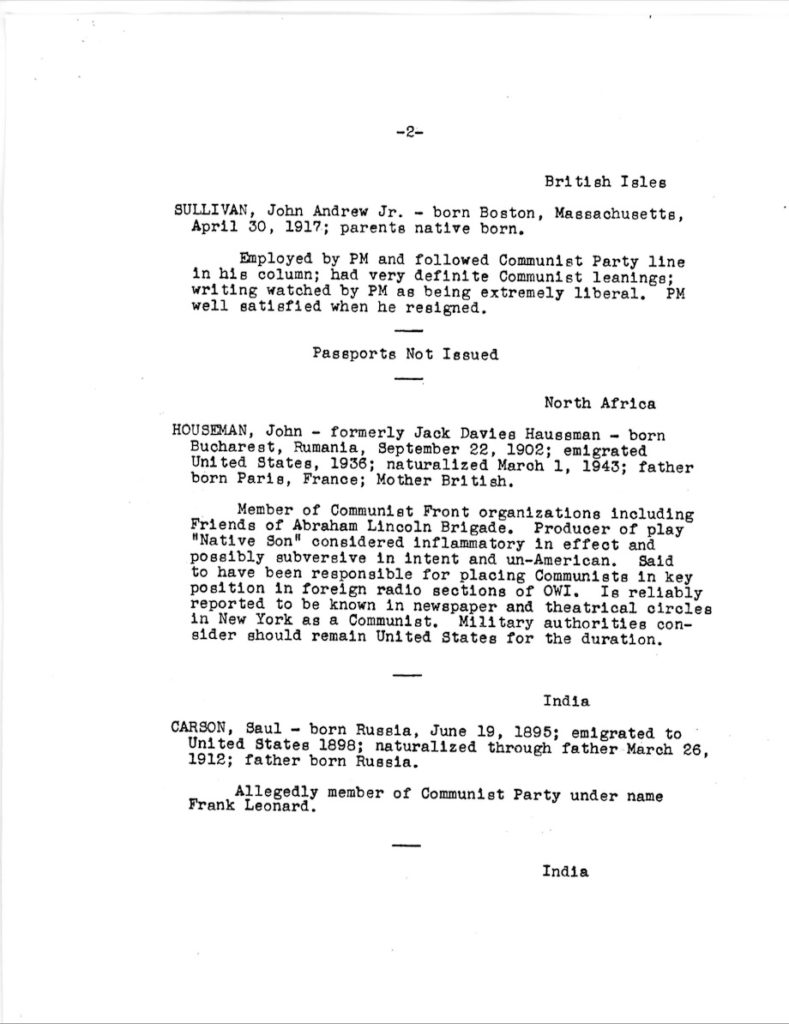

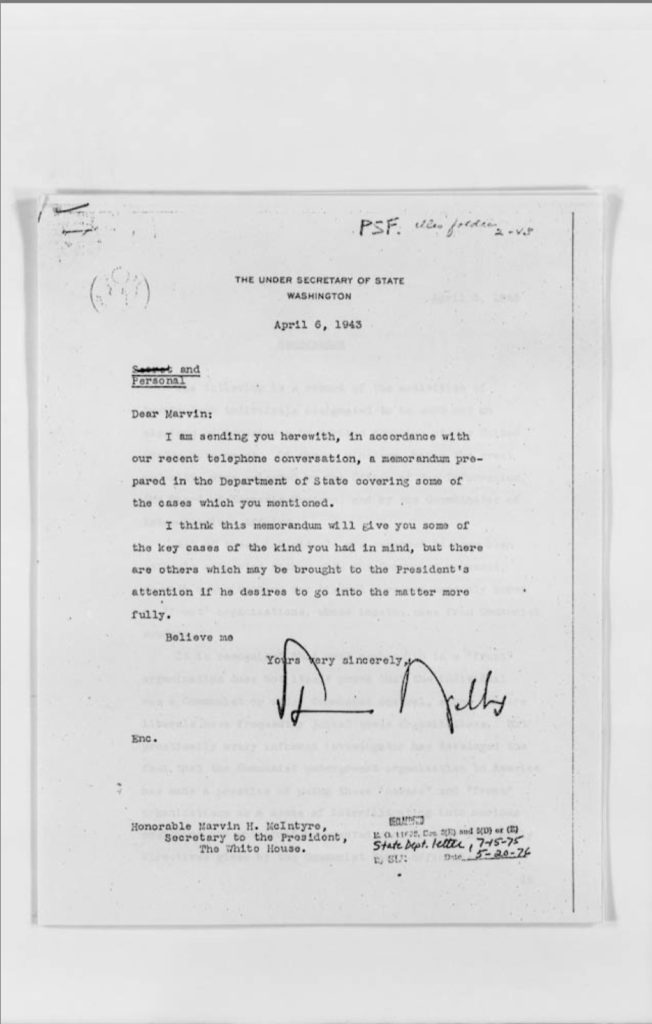

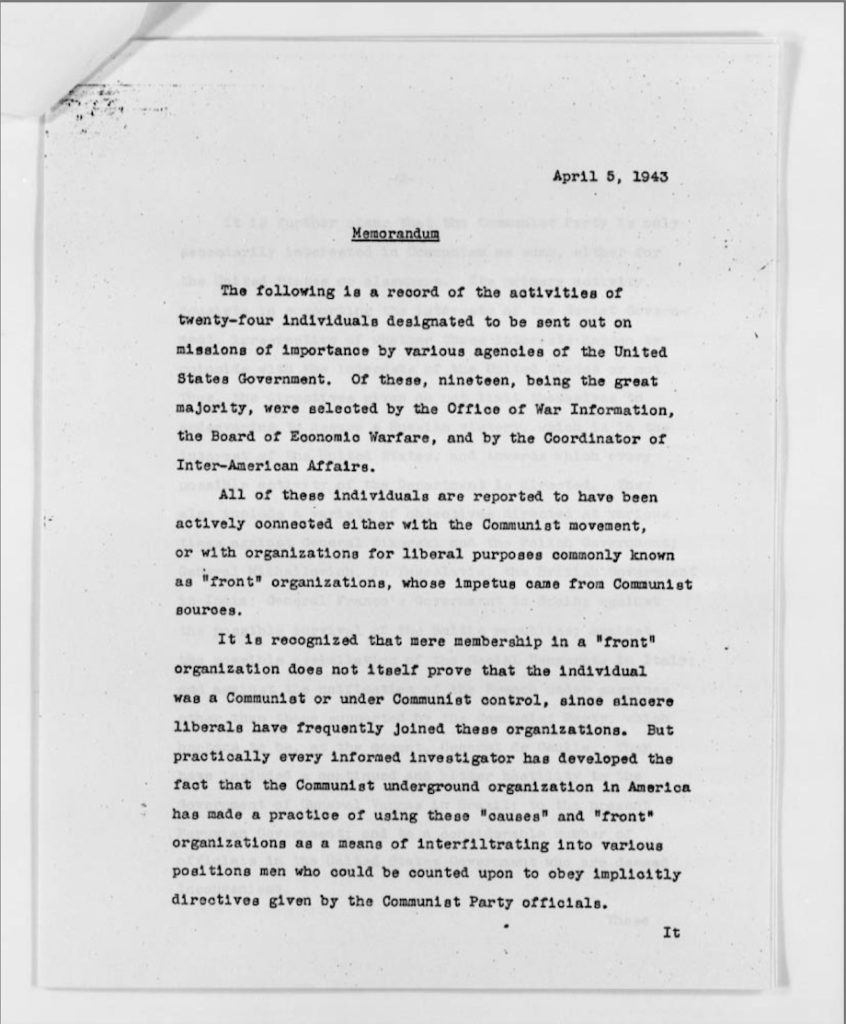

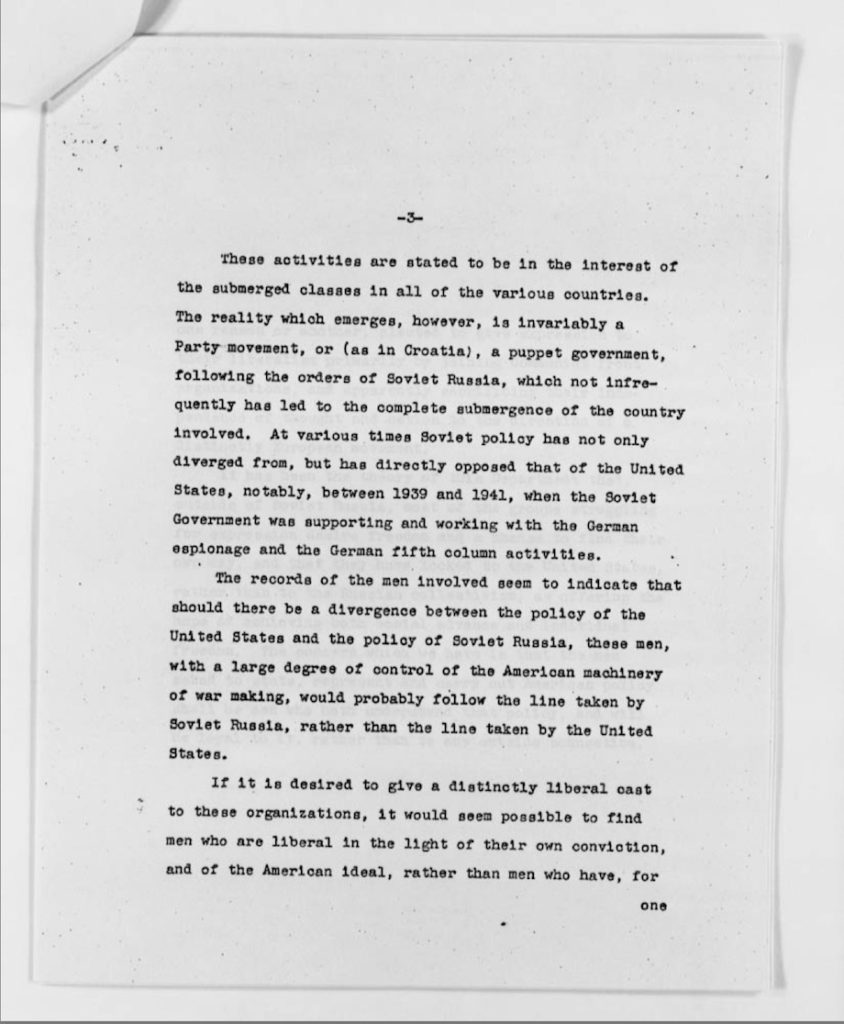

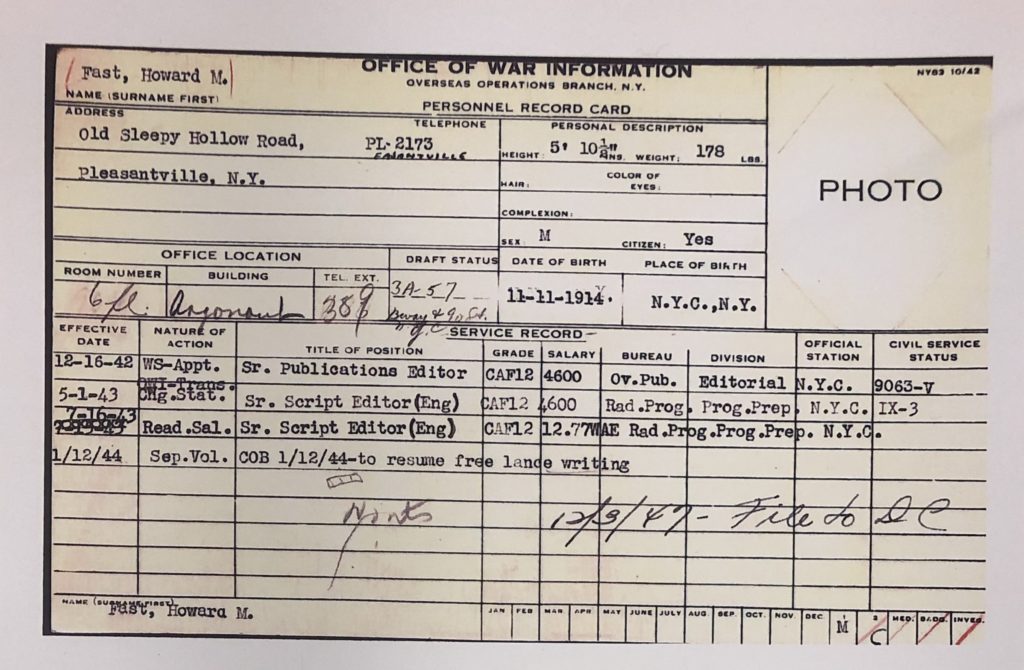

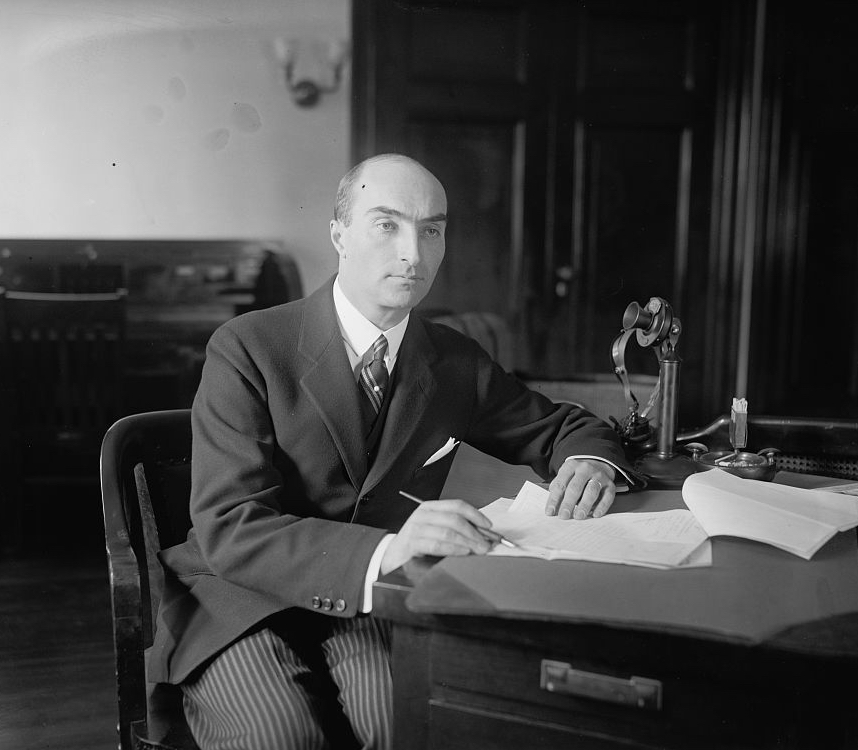

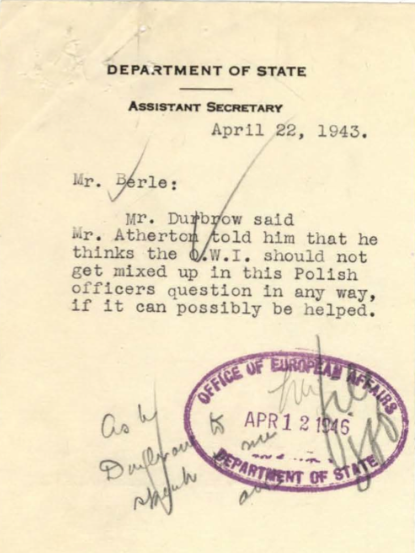

Hollywood actor John Houseman, the person often presented as the first Voice of America director, was suspected by the State Department and the Army Intelligence in 1943 of being a communist sympathizer who hired communists to fill Voice of America positions. The State Department and U.S. military authorities secretly declared him as untrustworthy to be issued a U.S. passport for official government travel abroad. VOA journalists may be astounded to learn that John Houseman was initially hired by William J. Donovan, the head of what was then the U.S. intelligence agency which later split from its overt propaganda arm. Propaganda and psychological warfare operations remained under the direction of FDR’s speech writer and Houseman’s patron, Robert E. Sherwood, who was also strongly pro-Soviet and participated in hiring Houseman, partly because of his reputation as a pioneer of radio propaganda broadcasting and his fame as a co-producer of the fake news radio play Men from Mars, an adaptation of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds . Also shocking to many VOA journalists who may have read descriptions of Houseman as a defender and symbol of accurate and objective journalism may be his own statements referring to VOA in his books as a propaganda and psychological operations outlet. In 1943, Houseman recruited Howard Fast to be Voice of America’s first chief news writer and editor. Fast became later a member of the Communist Party, an editor of its newspaper, The Daily Worker, and the 1953 recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize. In mid-1943, Houseman was secretly forced to resign from his VOA director’s position, but his pro-Soviet bosses kept giving him part-time work and unsuccessfully tried to hire him again in 1945. Howard Fast left VOA in early 1944 with a glowing recommendation from VOA’s second director Louis G. Cowan even though Roosevelt Administration officials in the State Department also refused to provide Fast with a U.S. passport for government travel abroad. Many pro-Soviet VOA broadcasters hired by Houseman continued working at the Voice of America until the late 1940s and in a few cases into the early 1950s. A few of the early VOA broadcasters ended up working as anti-U.S. propagandists for communist regimes.

Please note that BBG Watch and USAGM Watch neither represent nor endorse any of the individuals or groups profiled on this site.

Today’s Voice of America management still does not admit that VOA’s first director was a pro-Soviet communist sympathizer who, together with other like-minded journalists he had hired, helped to spread Soviet propaganda in VOA broadcasts during World War II and advocated for the establishment of pro-Soviet socialist governments in Central Europe.

This is his bio on the official VOA website as copied on March 20, 2020:

John Houseman, a Romanian-born immigrant and successful actor, author, and film producer, served as Voice of America’s first director just as World War II was entangling the Western world. In spite of a steady stream of bad news related to wartime losses, Houseman determined that VOA would tell listeners the truth, whether it was good for the U.S., or bad for the U.S. ”Only thus,” he explained, “could we establish a reputation for honesty which we hoped would pay off on that distant but inevitable day when we would start reporting on our own invasions and victories.” Houseman also introduced a style of radio reporting that employed multiple voices in individual broadcasts, a device he had learned through his theatrical background.

Prior to Voice of America, Houseman gained national recognition through his role in the production of the War of the Worlds radio broadcast in 1938, with Orson Welles. The story and sound effects were so realistic at the time that there were reports that some listeners actually believed that an extraterrestrial attack was imminent. Houseman was also an accomplished actor, with his role as Professor Kingsfield in The Paper Chase earning him an Academy Award for best Supporting Actor. Houseman continued his involvement in acting and theatre throughout the rest of his life.

USAGM WATCH Note: While Houseman was indeed born in Romania where his father worked as an international businessman, his father was a French citizen and his mother was British. Houseman lived in the United States until 1943 as an alien using a British passport. He did not become a U.S. citizen until after he was appointed to his U.S. government job in charge of Voice of America broadcasts. For part of his stay in the United States, Houseman was in violation of immigration laws and was in the country illegally, but with the help from his Office of War Information boss, President Roosevelt’s speechwriter Robert E. Sherwood, he was given U.S. citizenship in an expedited process. At that time he changed his name from Jacques Haussmann to John Houseman.

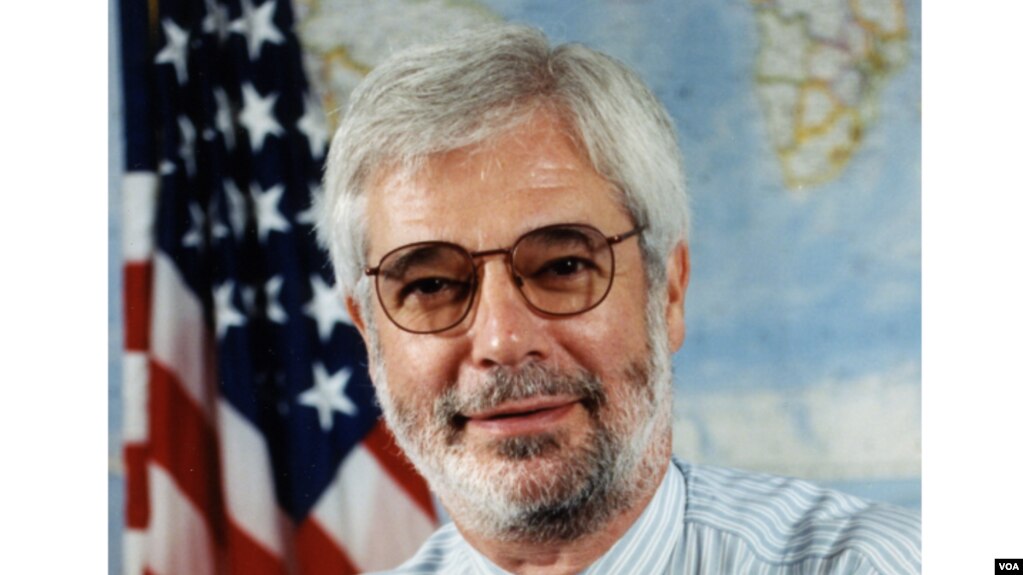

From Broadcasting Board of Governors’ NOTEBOOK, March 14, 2013:

“The journalistic integrity and reputation for honest reporting that John Houseman brought to the Voice of America as its first director in 1942 are part of the foundation upon which VOA was built,” said David Ensor, current [2013] Director of VOA, “and led to what it is today: one of the most widely respected international news organizations in the world.”

Though “War of the Worlds” lives on in radio legend while “The Paper Chase” only survives in the bargain bin of niche video stores, Voice of America is Houseman’s most important and most enduring legacy. Today VOA broadcasts accurate and reliable news to 134 million people in 45 languages, which makes it worthy of being called a masterpiece.

By Blake Stilwell

But Czesław Straszewicz, a Polish journalist based in London during the war, wrote in the 1950s about the harsh negative impact of VOA’s pro-Kremlin wartime broadcasts on the audience in Nazi-occupied Poland and among the free Poles abroad.

With genuine horror we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored.

I remember as if it were today when the (Warsaw) Old Town fell [to the Nazis] and our spirits sank, the Voice of America was broadcasting to the allied nations describing for listeners in Poland in a happy tone how a woman named Magda from the village Ptysie made a fool of a Gestapo man named Mueller.

Czesław Straszewicz, “O Świcie,” Kultura, October, 1953, 61-62. We are indebted to Polish historian of the Voice of America’s Polish Service Jarosław Jędrzejczak for finding this reference to VOA’s wartime role.