BBG Watch Book Review

U.S. Media Outreach Can Make A Big Difference Abroad

By Ted Lipien

Chen Guangcheng (born 12 November 1971) is a Chinese civil rights activist who worked on human rights issues, mostly in rural areas of the People’s Republic of China. Since May 2012, he lives in exile in the United States. A Wikipedia entry about Chen Guangcheng has this description of his pro-human rights advocacy: “Blind from an early age and self-taught in the law, Chen is frequently described as a ‘barefoot lawyer’ who advocates for women’s rights, land rights, and the welfare of the poor. He is best known for accusing people of abuses in official family-planning practices, often involving claims of violence and forced abortions.”

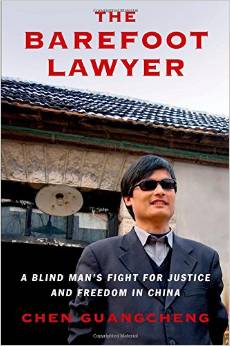

In March 2015 Chen published an autobiography, The Barefoot Lawyer, in which he wrote at some length about the importance of Radio Free Asia (RFA) and the Voice of America (VOA) in his life as a blind person committed to the cause of advancing human rights in China.

Chen Guangcheng in The Barefoot Lawyer (page 87):

“Beyond what I learned from my schoolwork, my awareness of politics and current events continued to deepen, largely thanks to what I heard on the radio. Radio Free Asia, the nonprofit service funded by the U.S. government, was a revelation.”

Chen heard Radio Free Asia for the first time while studying at a Chinese university as his roommate’s shortwave radio was picking up RFA’s program Listener Hotline. Listeners were invited to call in and could express any opinion on any topic or talk about their own experiences. Ordinary Chinese were talking about how they suffered from illegal actions by government officials and from discrimination.

What impressed him, Chen wrote, was that the calls from anti-U.S. Chinese nationalists were not censored by RFA. A station supported by the U.S. government apparently made no attempt to block criticism of the United States on its airwaves, Chen observed.

Chen also listened to Voice of America (VOA), Radio France Internationale (RFI), Deutsche Welle (DW) and the Sound of Hope, the Falun Gong radio station, but most of the comments in his book about radio listening in China refer to RFA programs.

Chen was even able able to listen to radio while in a Chinese prison where having a radio was extremely dangerous. A fellow prisoner had one smuggled in from the outside, allowing Chen to listen to Western radio programs with earphones while wrapped up in his blanket. He kept his radio hidden in his bed or in an empty milk carton especially modified for this purpose.

“I heard depressing stories about friends and fellow human rights defenders who were imprisoned, tortured, or under house arrest; I heard hopeful stories about ordinary citizens who were starting to defend themselves against the corrupt and powerful,” Chen wrote.

Chen also described how he learned from Western radio broadcasts about the harassment and beatings to which his wife, Weijing, was being subjected by the Chinese communist authorities.

“Over the radio I could make out the sound of her tears in the midst of the broadcast report,” Chen wrote. It’s one of the most powerful and moving observations in his book.

Chen’s autobiography also describes his ordeal at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing where he sought refuge in April 2012 after escaping from house arrest in rural China. He paints a mixed picture of American officials. Some come across as more understanding of human rights conditions and the oppressive nature of the political system in China than others, but most of them tried their best to help him and his family, subject to restrictions imposed on them from Washington. Chen is critical of President Obama and his White House staff while reserving considerable praise for former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Anyone reading Chen Guangcheng’s autobiography who can grasp the reality of life for millions of poor and oppressed people, not only in China but also in other nations, will appreciate the value of radio broadcasts and other news programs produced by Radio Free Asia, the Voice of America, Radio and TV Marti, Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, Alhurra TV and Radio Sawa.

To some degree, all of these stations, supported by U.S. taxpayers, struggle with the same dilemma as U.S. diplomats in Beijing and White House staffers in Washington who tried to negotiate a deal with the Chinese government in 2012 to allow Chen and his family some measure of freedom. For those who never experienced such misery as Chen did, it is not easy to understand what it means to be poor and oppressed.

When we think about media and technology, it is easy to forget about those who are desperately poor and seem powerless to us. It is easier to identify with those who are more like us. But Chen Guangcheng’s life is a powerful reminder of how information and ideas can have a great impact on people of whom most Americans would not think as potential new leaders in their countries.

In reading Chen Guangcheng’s book, I thought about Lech Walesa, a Polish worker who led a strike at a shipyard in Gdansk that changed his country’s history. Chen’s story about how listening to uncensored U.S. radio programs helped to shape his ideas is amazingly similar to what Lech Walesa told me in an interview almost 30 years ago and in other interviews after he became Poland’s President. These programs are still enormously important to millions of people. U.S. lawmakers and officials who are now working on reforming the management of U.S. international media outreach can learn a lot from Chen Guangcheng’s book.

Disclaimer: Ted Lipien is one of the co-founders of BBG Watch, former acting associate director of the Voice of America and former head of VOA Polish Service during Solidarity’s struggle for democracy.