BBG Watch History

April 13 is observed in Poland as Katyn Memorial Day. It commemorates over 22,000 Poles – chiefly officers and reserve officers – who were executed in April 1940 by the NKVD (a forerunner of the Soviet Union’s secret police organisation the KGB). During World War II, the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Voice of America (VOA) promoted the Soviet propaganda lie that the mass murder was committed by Nazi Germany. After the war, VOA started reporting that Katyn was most likely a Soviet crime, but censorship of the Katyn story continued at VOA sporadically until the 1970s, while Radio Free Europe (RFE), another U.S. government-funded broadcaster, did not restrict its Katyn coverage. Today we repost a paper on Voice of America and Katyn written by former VOA Polish Service director and former VOA acting associate director Ted Lipien. The report includes a link to a Voice of America radio broadcast on the Katyn massacre recorded in April 1943 by the Office of War Information director Elmer Davis.

The Triumph of Propaganda – Voice of America and Katyn

By Ted Lipien

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) online catalog contains several declassified documents showing how U.S. State Department diplomats tried and failed to prevent U.S. government-funded broadcaster, the Voice of America (VOA), from spreading the Soviet propaganda lie during World War II about the mass murder of thousands of Polish Army officers and intellectual leaders captured by the Soviets during their invasion of Poland in September 1939.

On April 13, 1943, Nazi Germany announced the discovery by German troops of several mass graves containing the remains of Polish POWs in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk in the Soviet Union. 4,400 Poles were buried in Katyn, each victim shot in the back of the head.

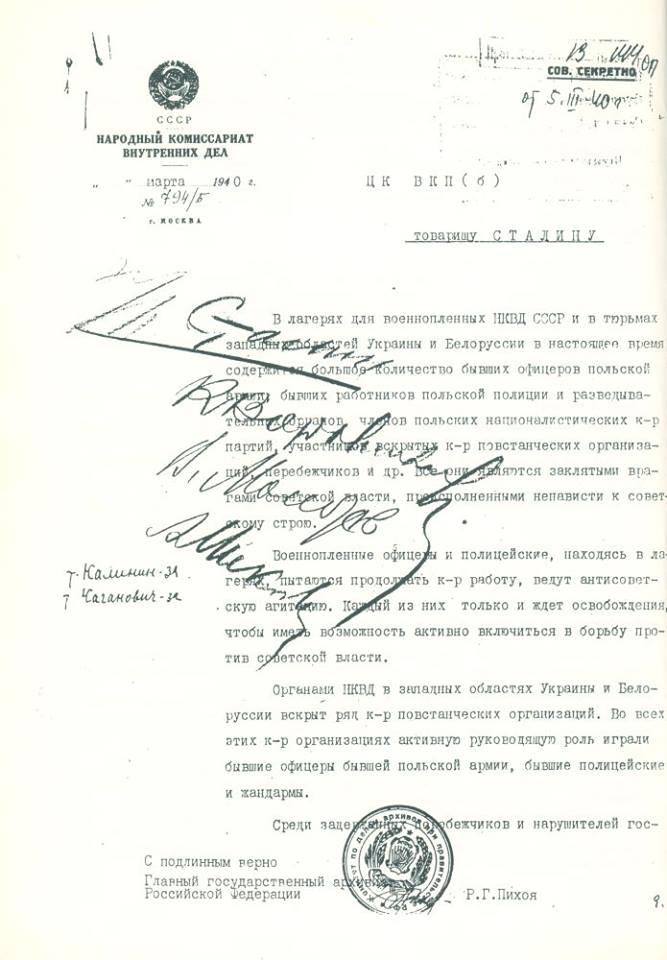

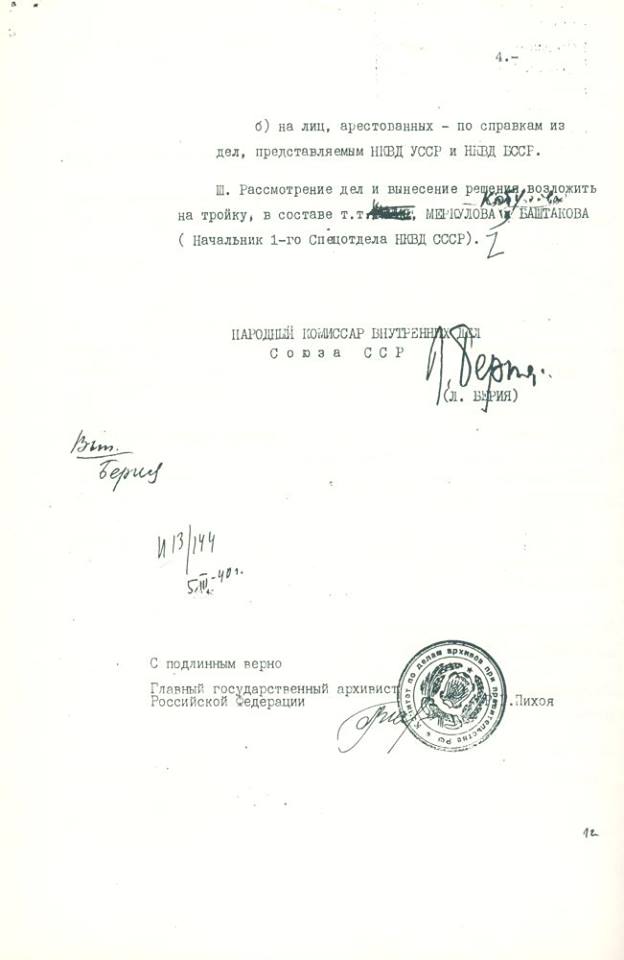

Two days later, on April 15, 1943, the Soviet government blamed the massacre on the Germans. It was an outright Soviet lie since in March 1940 Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, NKVD secret police chief Lavrentiy Beria and other members of the Soviet Politburo had ordered the execution of more than 22,000 Polish war prisoners, including twelve generals.

The executions were carried out the Soviet NKVD (a forerunner of the KGB) in the spring of 1940 in Katyn and at other locations. When the Polish Government in Exile requested an investigation by the International Red Cross, Moscow used it as a pretext to break diplomatic relations with the Polish Government based in London. The break in diplomatic relations announced by the Soviet government on April 25, 1943 was part of Stalin’s plan to establish a communist regime in Poland after the war.

After the Soviet announcement of April 15, 1943, the Voice of America immediately accepted and promoted Soviet claims on the Katyn massacre, acting against advice from the State Department.

False Soviet propaganda was repeated in VOA news bulletins and in a special radio broadcast commentary recorded by Elmer Davis, the head of VOA’s government agency, the Office of War Information (OWI). While the transcript of Elmer Davis’ Katyn broadcast was already made public by a committee of the U.S. Congress in 1952, a recording of his broadcast was only recently discovered in the WNYC New York public radio station’s online audio archives.

Americans were not all uncritically pro-Soviet even after the Soviet Union became America’s ally against Nazi Germany. Outside of the executive branch including the Voice of America, many members of Congress continued to raise concerns about Stalin’s brutal rule and his earlier alliance with Hitler which led to the outbreak of World War II and the division of Poland in 1939 by the two dictators. In addition to lawmakers and some U.S. diplomats familiar with the Soviet Union, many American journalists and leaders of ethnic organizations were also warning that Stalin would soon occupy and try to enslave Eastern Europe to the detriment of other U.S. wartime allies and future Western security. President Roosevelt and some U.S. military leaders, however, tried to prevent such information from harming the wartime military alliance with Russia. Both the White House and the State Department viewed the Soviet military as absolutely essential to winning the war with Germany and Japan, but the State Department was starting to take a much more nuanced view than the White House or pro-Moscow Voice of America journalists.

When Germany announced the discovery of the Polish officers’ graves in Katyn in April 1943, in an unusual move for senior American diplomats, the State Department began urging the Voice of America to show caution when reporting on the massacre in order to avoid being caught later in a lie. These diplomats representing the top echelon of American elite were becoming concerned about the integrity of information being released by the U.S. government and America’s long-term interests. The OWI and VOA leadership dominated by unabashedly pro-Soviet propagandists ignored repeated warnings from the State Department not to get burned by the Katyn story by careless reporting and one-sided commentary. Wartime VOA continued its long-established pro-Moscow line with the approval from its top leadership and the Roosevelt White House.

President Roosevelt either refused to believe that Stalin could have committed such a crime even when presented with evidence pointing to the Soviet guilt, or found it necessary to ignore it. But by the spring of 1943, some U.S. diplomats were becoming sufficiently alarmed by the behavior of America’s Soviet ally. U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union Admiral William H. Standley and the Ambassador of the Polish Government-in-Exile Jan Ciechanowski provided the State Department with considerable evidence that thousands of Polish officers taken prisoner by the Soviets in 1939 had gone missing in Russia sometime in the spring of 1940 and were most likely dead. Ambassador Ciechanowski also gave the same information to Elmer Davis and other officials in charge of the Office of War information and the Voice of America.

In his 1947 book “Defeat in Victory,” Ambassador Ciechanowski wrote:

“Of all the United States Government agencies, the Office of War Information [where Voice of America was placed], under its new director, Mr. Elmer Davis, had very definitely adopted a line of unqualified praise of Soviet Russia and appeared to support its shrewd and increasingly aggressive propaganda in the United States. The OWI broadcasts to European countries had become characteristic of this trend.”

Describing his June 1944 meeting in Washington with U.S. Undersecretary of State Edward Stettinius, Prime Minister of the Polish Government in Exile Stanisław Mikołajczyk recalled:

“I mentioned also the tone of OWI broadcasts to Poland. They had been following the Communist line consistently, which made our own job more difficult.”

“‘It’s unwise to adopt this approach to the Polish people,’ I told the Undersecretary (Stettinius). ‘If you continue to call Russia a ‘democracy,’ you may eventually regret that statement, and your people will condemn you.”

“Your government once called Poland ‘the inspiration of the nations,’ but now the OWI calls the Communist forces just that. Please don’t think we haven’t tried to make friends with Russia, for we have. Poland just does not want to become another Red satellite.”

The Polish prisoners had vanished in 1940, more than a year before the German attack on the Soviet Union, while being held in Soviet prison camps. Except for OWI and VOA officials, few unbiased and well-informed journalists believed in Stalin’s explanation that thousands of Polish prisoners could have evaded the Soviet secret police and escaped to Manchuria, or simply disappeared within Russia without any trace.

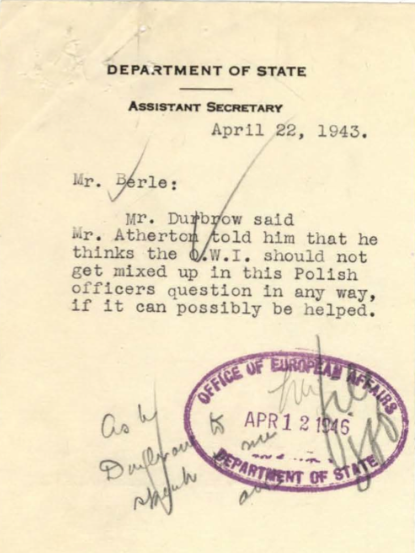

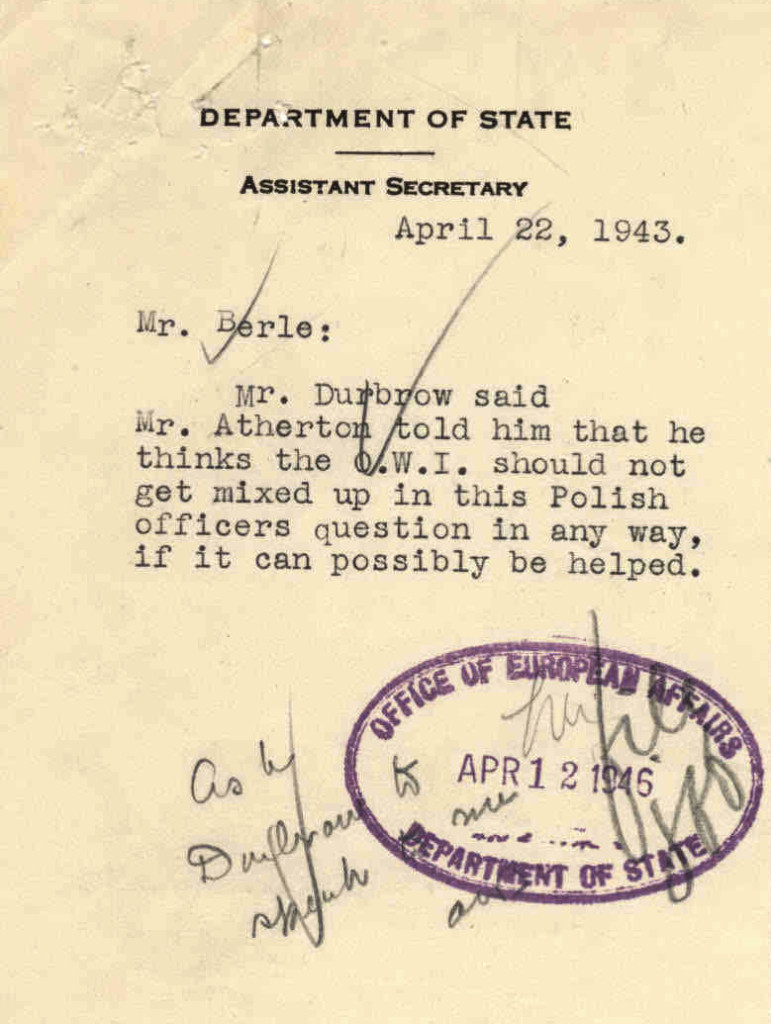

After Joseph Goebbles’ propaganda machine announced the discovery of the Katyn graves on April 13, 1943, a note dated April 22, 1943 addressed to Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A. Berle included a warning for the OWI to exercise caution in reporting on the Katyn story. Voice of America was at that time OWI’s overseas broadcaster.

“Mr. Berle:

Mr. [Elbridge] Dubrow said Mr. [Ray] Atherton told him that he thinks the O.W. I. should not get mixed up in this Polish officers question in any way, if it can possibly be helped.”

Elbridge Dubrow and Ray Atherton were high-level State Department officials responsible for European affairs.

The State Department was by then aware that the OWI Director, American radio journalist Elmer Davis, and the Voice of America leadership, were already fully engaged in blaming the Katyn massacre on Nazi Germany.

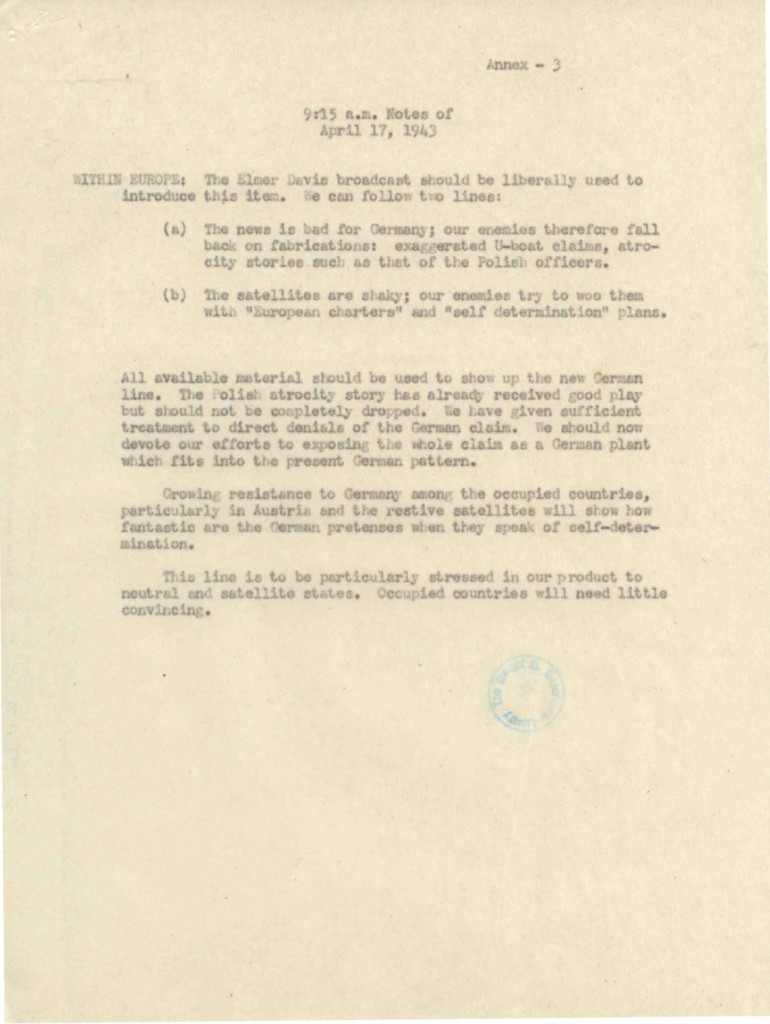

OWI meeting notes of April 17, 1943 advised staff:

“The Elmer Davis broadcast should be liberally used to introduce this item [Katyn].”

“The news is bad for Germany; our enemies therefore fall back on fabrications: exaggerated U-boat claims, atrocity stories such as that of the Polish officers.”

OWI April 17, 1943 meeting notes continued:

“The Polish atrocity story has already received good play but should not be completely dropped. We have given sufficient treatment to direct denials of the German claim. We should now devote our efforts to exposing the whole claim as a German plant which fits into the present German pattern.”

Elmer Davis initiated his broadcast for the Voice of America even though another memorandum from the Department of State dated April 22, 1943 warned:

“…a propaganda campaign which OWI wishes to start in order to counteract the German propaganda story regarding the alleged execution of some 10,000 Polish officers by the Soviet authorities. It is felt that because of the extremely delicate nature of the question of the alleged execution of these Polish officers, and on the basis of the various conflicting contentions of all parties concerned, it would appear to be advisable to refrain from taking any definite stand in regard to this question.”

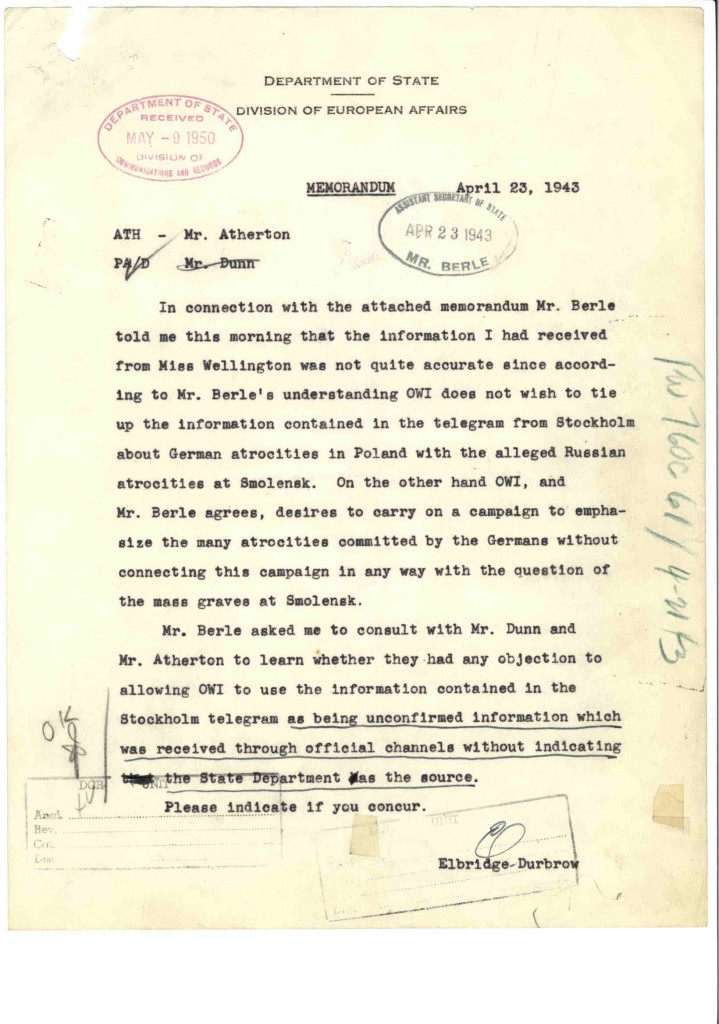

A State Department memorandum dated April 23, 1943 suggests that OWI officials may have told U.S. diplomats that they were not planning to blame the Katyn massacre squarely on the Germans and tie it to German atrocities committed in Poland. This could have been an attempt to mislead Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle. In his subsequent Voice of America broadcast, OWI director Elmer Davis did exactly the opposite of what the State Department memo said. He blamed the Germans for the Katyn massacre and tied it to German atrocities committed earlier in Poland.

In a U.S. domestic broadcast on April 30, 1943, Elmer Davis asserted:

“The Germans are known to have slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Poles after the fighting was over [in 1939]. If they found a camp full of Polish prisoners, when they attacked Russia [in 1941], it would have been the most natural thing in the world for them to murder them, too — if not at the moment, then later, when they needed the corpses for propaganda.”

The same Elmer Davis broadcast was heard overseas on the Voice of America on May 3, 1943, which happened to be Poland’s Constitution Day.

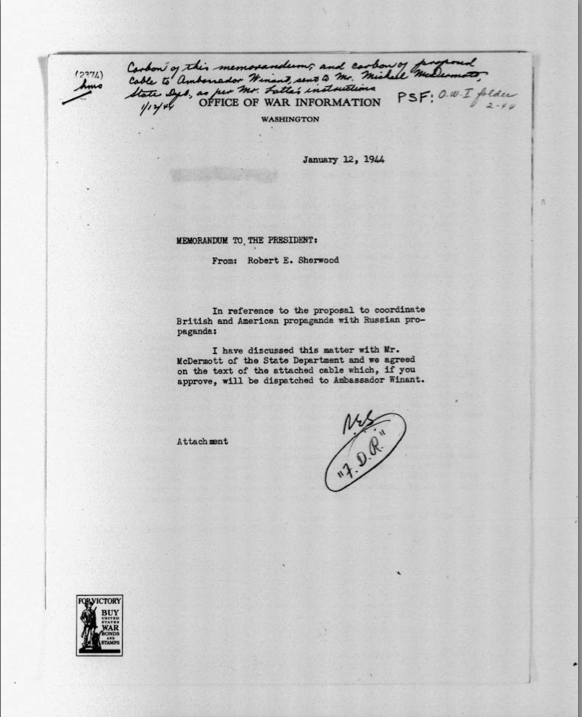

To the shock and disbelief of anti-Communist radio listeners in Eastern Europe and in the West, during World War II the Voice of America ignored news of Soviet atrocities, old and new, and even lauded Stalin as a radical democratic leader. The Roosevelt White House wanted VOA to promote the message of Russia as a freedom-loving and reliable ally. During the war, Russian was the only major language missing from Voice of America broadcasts. Russian broadcasts from America would have annoyed Stalin and were not launched until 1947. OWI director Elmer Davis had no problem with proposing in December 1942 to dispatch an OWI representative to Moscow with the rank of minister. The OWI already had such representatives at U.S. embassies in other countries. In January 1944, OWI Overseas Branch director Robert E. Sherwood proposed to the Roosevelt White House “to coordinate British and American propaganda with Russian propaganda.” The proposal was meant to strengthen coordination which was already well-established at the Voice of America.

On September 18, 1951, the United States House of Representatives established the Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence, and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, known as the Madden Committee after its chairman, Rep. Ray J. Madden of Indiana. One of its purposes was to determine whether any U.S. government officials had engaged in covering up the news of the massacre.

When questioned in 1952 by the Madden Committee, Elmer Davis said he did not remember discussing Katyn with high-level State Department officials or seeing the memorandum to Assistant Secretary Berle. He also said that he was convinced at the time that the crime had been committed by the Germans and only changed his opinion after the war when more information about Katyn became available. Elmer Davis was questioned by John J. Mitchell, the Madden Committee’s chief counsel.

Mr. Mitchell. Mr, Davis, you have told us previously that on overall policy and on high-level policy matters, you discussed those with Mr. Hull and Mr. Welles. I would like to ask you now whether you ever discussed this matter specifically at this time with the Department of State or any official therein?

Mr. Davis. I don’t remember. I may say, Mr. Counsel, that this was not one of the major issues that I had to deal with at that time, from my point of view. To a Pole it was certainly the most important issue in the world, but to me, as to the head of every department or agency of Government, about that time of year the principal question was how his budget was- going to get through Congress, and that absorbed most of my time. So whether I asked advice on this question from either Mr. Hull or Mr. Welles, I don’t remember. I don’t recall seeing this memorandum from Mr. Berle, although it is conceivable that I might have. I don’t know.

The Congressional Committee investigating the Katyn Massacre concluded in 1952 in its Final Report:

“Mr. Davis, therefore bears the responsibility for accepting the Soviet propaganda version of the Katyn massacre without full investigation.” “A very simple check with either Army Intelligence (G-2) or the State Department would have revealed that the Katyn massacre issue was extremely controversial.”

Elmer Davis refused to accept any responsibility and instead lashed out at his critics who had warned him during the war about Soviet propaganda in Voice of America programs and Soviet sympathizers working at the Office of War Information.

Elmer Davis was especially dismissive of the late Congressman John Lesinski, Sr. (D-MI) and former Polish Ambassador to Washington Jan Ciechanowski. Elmer Davis was questioned by Rep. Thaddeus M. Machrowicz (D-MI).

Mr. Machrowicz. “You have no recollection of either Ambassador Ciechanowski or Congressman Lesinski warning you about the fact that these three persons were known Communists, and were in the employ of the Office of War Information?”

Mr. Davis. “I don’t remember that Mr. Lesinski ever warned me about anything, Mr. Ciechanowski, perhaps by his excessive number of warnings, made me forget which particular ones he especially spoke about.”

The first Voice of America director, Hollywood actor John Houseman also took a few barbs at the Poles and Polish Americans in his book “Unfinished Business Memoirs: 1902-1988” and perhaps unwittingly repeated a few Soviet propaganda themes that VOA under his leadership promoted during the war by denying Soviet crimes and supporting Soviet territorial demands against America’s wartime ally against Nazi Germany and the first victim of World War II attacks by Hitler and Stalin.

“Why were the Poles, after centuries of partition and suffering, riddled with anti-Semitism and obsessed by mad dreams of a ‘Greater Poland’.”

Like his boss Elmer Davis, John Houseman also referred to Voice of America programs as designed for psychological warfare and propaganda. When the State Department refused to issue him a U.S. passport for official travel to Europe and North Africa, John Houseman blamed it on Polish Americans.

“To explain this refusal various theories were put forward: one was that Mrs. Shipley, head of the Passport Division, being herself of Polish origin, was taking revenge for the injuries supposedly inflicted on the Polish Government-in-Exile by the Voice of America.”

Later, according to Houseman, Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle, no doubt fed up with some of VOA’s more irresponsible propaganda broadcasts, himself turned down Houseman’s passport application. John Houseman resigned as the director of the Voice of America in 1943.

VOA programs at that time and even after John Houseman’s resignation were viewed as harmful not only by various governments-in-exile opposed to the Nazis but found unacceptable by the Soviet Union. Non-communist resistance fighters and audiences throughout Europe also found Soviet propaganda in VOA programs offensive and complained about censorship. “With genuine horror we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored,” wrote a Polish journalist based in London during the war.

After the war, several of VOA’s foreign language broadcasters and their spouses left the United States to work for the communist regimes in Eastern Europe as anti-American propagandists. One of them, Stefan Arski, had worked on VOA’s Polish desk during the war. In communist-ruled Poland, this former VOA broadcaster wrote anti-American propaganda and penned commentaries denying any Soviet role in the Katyn massacre. In a 1952 article in the Polish Communist Party daily Trybuna Ludu, titled “Propaganda of Genocide’s Perpetrators,” this former VOA wartime commentator called the activities of the U.S. congressional commission investigating the Katyn Massacre “a gross provocation” equal to the original provocation of the Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. In his article, Stefan Arski condemned the Voice of America coverage of the Katyn hearings. In another article, he described Radio Free Europe as being created by “the flower of America’s dark reactionary forces, fascism, and imperialist domination.”

Another defector who became a communist official, Dr. Adolf Hofmeister, had been in charge of VOA’s wartime broadcasts to Czechoslovakia. OWI’s chief Elmer Davis admitted knowing Dr. Hofmeister, but he claimed that he did not know Stefan Arski, alias Artur Salman, who had worked for him during the war at OWI’s Polish desk.

Another contributor to OWI and VOA programs of Katyn fame was Kathleen Harriman, a daughter of President Roosevelt’s ambassador to Russia, W. Averell Harriman, who at the request of her father went to observe the Soviet exhumation of Polish officers’ bodies at Katyn in 1944 after Soviet troops retook the area. After her visit to Katyn, she wrote a report for the U.S. Government endorsing the Soviet claim that the Poles had been killed by the Nazis.

According to former U.S. Ambassador to Poland, Arthur Bliss Lane, her report was the only one in the Katyn file at the State Department at the end of the war. She testified before the Katyn Committee under her married name Mrs. Kathleen Mortimer. In her testimony, she tried to minimize her OWI work and said that she had not reported from Katyn for OWI. It was her official report to the U.S. Government that caused confusion and mislead officials in Washington, but her conclusion that the Soviets were innocent of the mass murder was exactly what her father, President Roosevelt and Stalin wanted to hear.

According to Polish officer Captain Jozef Czapski who was one of the few not killed by the Soviet NKVD secret police and was charged by the Polish Government in London with a futile search for the missing soldiers, Mr. Harriman’s report to the U.S. Government did tremendous damage.

The State Department also could not provide its diplomat going to Warsaw in 1945 as U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet-dominated regime in Warsaw numerous other U.S. and Polish reports pointing to the Soviet guilt for the Katyn murders. Numerous U.S. military and diplomatic reports shedding true light on the Katyn massacre were classified, hidden or seemed to have mysteriously disappeared. The only report the State Department could show to Ambassador Bliss Lane in 1945 was written by an OWI-VOA freelancer Kathleen Harriman who at the time was only 26 years old.

The Madden Committee concluded in 1952 that American policy toward the Soviet Union might have been different if information deliberately withheld from the public had been made available sooner.

A partial and sporadic coverup of the Katyn story continued at the Voice of America until the 1970s, but individual VOA journalists, especially in the Polish Service, in VOA’s European Division and among some VOA Central Newsroom reporters, tried their best to overcome bureaucratic obstacles and censorship. Radio Free Europe (RFE), also funded by the U.S. government, operated with far fewer constraints than VOA. RFE had a major impact by providing uncensored news and shaping public opinion in communist-ruled Poland during the Cold War, but it did not exist during World War II. VOA programs to Poland improved greatly during the Reagan Administration which supported the Solidarity trade union’s struggle for democracy in the 1980s.

Soviet propaganda triumphed at the Voice of America during World War II and to some degree continues to triumph today because VOA and most of the historians writing about VOA have never acknowledged the power of Soviet propaganda and its influence within the Office of War Information and at the Voice of America in its early years. This unpleasant history was being ignored, hidden and replaced with a narrative that from its very beginning the Voice of America operated under the slogan: “The news may be good. The news may be bad. We shall tell you the truth.” Those words were indeed spoken by journalist William Harlan Hale in the very first VOA broadcast in 1942. They were not always followed.

Disclosure: Ted Lipien is one of the co-founders and supporters of BBG Watch.