Smart Soft Power Diversified

Diversified Outreach of U.S. Media and Public Diplomacy During the Cold War – American Diplomats and Broadcasters Discuss Impact of Voice of America and Radio Free Europe in Poland

By Ted Lipien

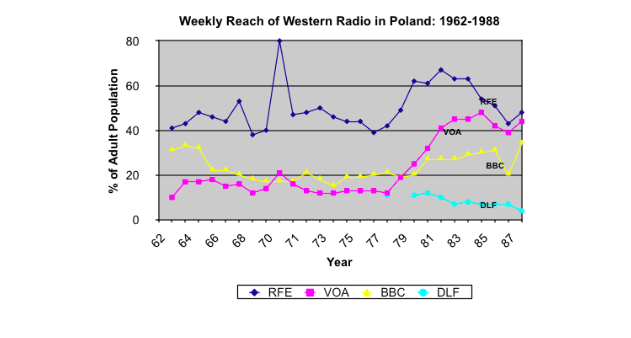

Unlike today, during the Cold War, U.S.-funded radios, Voice of America (VOA), Radio Free Europe (RFE) and Radio Liberty (RL), were highly popular and successful in countering anti-American propaganda. Unlike today, VOA and RFE/RL, were not under one centralized and dysfunctional management.

Equally effective in a different way during the Cold War was a separate U.S. public diplomacy and cultural diplomacy effort run by the United States Information Agency (USIA). Voice of America also engaged in public diplomacy, as well as in cultural diplomacy through various radio broadcasts, including “Music USA” jazz programs hosted by Willis Conover. For several decades, USIA was VOA’s parent federal government agency. RFE and RL were non-federal entities and had their own highly-focused and specialized management and oversight board.

But in the last twenty years, something has gone terribly wrong. The House Foreign Affairs Committee is calling the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), which is now in charge of all U.S.-funded media outreach oversees, “a broken agency.” “This Broken Agency is Losing the Info War to ISIS & Putin,” a committee press release says. President Obama fails to mention the BBG while outlining plans to counter ISIL on the ideological front. A small group of VOA English newsroom reporters insists that countering violent extremism and Putin propaganda would violate their journalistic integrity. Audience engagement on the VOA English news website is minimal. Employee morale has been so low that well-known and respected scholar of public diplomacy and media, Martha Bayles, made an unusual appeal to the Broadcasting Board of Governors to appoint as soon as possible a qualified outside candidate to lead RFE/RL. A $400 million anti-discrimination class action lawsuit has been filed against the BBG in a federal court on behalf of its contract employees who claim that they are doing U.S. government work but are denied by the management salaries and benefits of federal workers.

U.S. public diplomacy, now firmly within the State Department, is doing just as poorly against ISIL and Putin propaganda. The Iranian opposition is convinced that we have abandoned them, President Obama announced a major move of his “Reset” with Russia on the anniversary of the Soviet invasion of a neighboring county. The “Reset” policy itself was a fiasco. The State Department’s public diplomacy couldn’t even get the spelling of “Reset” right in Russian for Secretary Clinton. The Cuban opposition thinks we have betrayed them. That’s not how public diplomacy should perform for America.

Some BBG managers and reporters use arguments in favor of journalistic freedom and journalistic integrity as an excuse to justify failure, poor judgement or lack of objectivity. A Radio Liberty Russian Service manager, believed to be still in the same position, said in an interview shortly after journalist Anna Politkovskaya was assassinated in Russia in 2006 that RL had confidence in Vladimir Putin as a reasonable leader. BBG managers did not think for a moment it was a bad idea for their U.S. Government agency to order a public opinion poll in an illegally annexed territory like Crimea in 2014 and report with pride that nearly everybody loves Putin. They somehow overlooked the Crimean Tatars and Ukrainian refugees. Public diplomacy at State said nothing to disavow what BBG managers said about Crimea. VOA repeated faulty poll results promoted by BBG managers.

Why almost nothing seems to be working in the battle for hearts and minds?

During the Cold War, the traditional State Department diplomacy effort was focused on trying to make communist regimes in Eastern Europe less dependent on Moscow. While the State Department and the White House were criticized at times for becoming too chummy with these regimes, this perception was counterbalanced by USIA programs, VOA, and especially RFE and RL. It all worked. The combined success was due in large part to successive U.S. administrations and the U.S. Congress recognizing distinctive roles of traditional government-to-government diplomacy, public and cultural diplomacy, U.S. media outreach through the Voice of America, and the so-called surrogate broadcasting by Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. There were tensions and competition between traditional diplomacy and various elements of America’s soft power. Each had a different role to play. Together, they won the Cold War.

These important distinctions were fatally weakened with the consolidation of USIA into the State Department and the creation of the Broadcasting Board of Governors in the 1990s. America’s “smart power” was centralized and bureaucratized.

As seen in this latest press release, the BBG’s bureaucracy now prides itself on pushing for even more consolidation between VOA and the surrogate media with the end result being a “practically defunct” agency, as aptly noted in 2013 by the then Secretary of State and BBG member Hillary Clinton. She bemoaned America’s inability to engage in the war of ideas. The February 26, 2016 BBG press release touts “BBG Networks Present A Unified Strategy.” For anyone who is familiar with the history of U.S. media outreach and public diplomacy, this statement and some of the details in the press release highlight a problem rather than a solution. Had U.S. media outreach strategy been unified to the same degree during the Cold War as presented in the BBG press release, either Voice of America or Radio Free Europe would not have been effective in carrying out their different missions.

The failed BBG bureaucracy has an obvious interest in keeping the status quo and increasing its power. Unfortunately, some BBG members and executives who have considerable experience in the private media sector lack any experience in foreign affairs, public diplomacy, U.S. international media outreach and government operations. As private media entrepreneurs, they see clearly benefits in centralization of management and consolidation of control. Any successful business person understands the advantage of having a market monopoly and full control of their businesses if they can legally achieve it. Their natural entrepreneurial tendencies are reinforced by BBG government bureaucrats who want the same thing for themselves for different, far more selfish reasons.

Yet we know that neither U.S. public diplomacy nor U.S. media outreach is working under this increasingly unified approach. Political leaders like Hillary Clinton, House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Ed Royce, Ranking Member Elliot Engel and numerous members of Congress of both parties know the history of American broadcasting and public diplomacy much better than most BBG members. They understand the distinctions between various elements of soft power. Some longtime BBG bureaucrats also know it, but it is not in their personal interest to acknowledge this history or to share it with the BBG board. Some board members appear to be completely unfamiliar with how the United States had successfully exercised its soft power in the past through a variety of different institutional venues without subjecting them to central control, which would have destroyed their unique strengths and effectiveness.

As someone who had participated in that effort, I have put together observations about the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe in Poland made by highly experienced U.S. diplomats and broadcasters. Most of them had worked for the United States Information Agency. Many of them did not have any direct role in VOA or RFE operations, but they had more appreciation for uncensored U.S. radio broadcasts to Eastern Europe than their contemporary State Department colleagues who were trying to maintain a diplomatic dialogue with East European communist regimes, also for the long-term benefit of the United States, but in a different way.

Some USIA officers whose observations I will cite in this article, however, had served in key executive positions at VOA on temporary U.S. Foreign Service assignments. During the Cold War, there was interweaving of U.S. public diplomacy and media outreach through VOA, which foreign audiences appreciated. At the same time, the surrogate broadcasters vigorously guarded their independence and ability to engage in the war of ideas, which foreign audiences in Eastern Europe appreciated even more.

I believe it’s rather obvious from these historical accounts that a diversified approach was far more effective than the bureaucratic centralism being proposed by the current BBG board and its bureaucracy. Just as consolidating public diplomacy into the State Department has resulted in a number of spectacular failures, so has the current BBG policy of centralization and consolidation of media outreach without any regard for what works and what does not. Bigger is not always better, especially in government. That’s why the U.S. political system and government operations have always been based checks and balances. Central planning does not work for any kind of creative activity, especially in the digital age, especially in government. With many news sources and delivery platforms competing for audience’s attention, there is a need for more flexibility, more creativity and more independence — not more unification under a government bureaucracy.

The reminiscences by American public diplomacy professionals I have put together as they relate to Poland and U.S.-Polish relations, also show that the United States was able to attract extraordinarily talented and experienced individuals, both diplomats and journalists, to help us win the Cold War. That’s no longer true at the BBG. Whatever good journalists remain, they are being stifled by the bureaucracy which replenishes itself with people with similar backgrounds and abilities. Most of them never leave government service until they are ready to retire. Former USIA public diplomacy officers, on the other hand, had to pass a rigorous Foreign Service exam and learn foreign languages and cultures. During the Cold War, VOA, RFE and RL were far more selective in their hiring practices — RFE and RL far more selective than VOA. While not all Foreign Service Officers were outstanding, most were exceptionally talented. The few bad ones did not stay in one job forever. When they were not promoted, they had to leave the Foreign Service.

The diplomats quoted here all had outstanding careers and made great contributions to the winning of the Cold War, whether at USIA, VOA, or the State Department. It’s obvious from reading these interviews what a great intellectual effort and talents of many highly trained individuals were needed to launch and sustain a successful counter to Soviet and communist propaganda. The idea that one “empowered” BBG CEO, no matter how good a manager he or she is, can now coordinate and oversee from the center of a Washington bureaucratic agency the entire U.S. media outreach effort and possibly also some of the public diplomacy and cultural diplomacy outreach, is monumentally misguided. He or she does not have anything even approaching the pool of talent that helped the United States win the Cold War. BBG officials and some poorly trained and poorly supervised journalists make embarrassing foreign policy-related and journalistic mistakes almost on a daily basis.

These accounts are not presented in any historical chronological order, but rather in terms of their connection to either VOA or RFE and relevance for understanding today’s problems of U.S. media outreach and public diplomacy. The interviews with former USIA and State Department diplomats who had served in Poland were conducted for the Foreign Affairs Oral History Collection by the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, Arlington, VA, www.adst.org. Direct link: http://adst.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Poland.pdf Copyright Foreign Affairs Oral History Collection, Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, Arlington, VA.

Even without focusing on today’s problems, these interviews offer a glimpse into fascinating history of U.S. broadcasting and diplomacy during the Cold War. For those interested in learning more, full interviews can be read on the ADST website.

Dell Pendergrast was Information Officer, USIS Warsaw (1974-1977). He was born in Illinois in 1941. He received his BA from Northwestern University and his MS from Boston University. His positions abroad included Belgrade, Zagreb, Saigon, Warsaw, Brussels and Ottawa. Charles Stuart Kennedy interviewed him on June 24, 1999.

DELL PENDERGRAST: “The public diplomacy we usually practiced at USIA has always focused on the long term, on what lies down the road, the ultimate outcome we’re trying to accomplish and encourage. Too often, in my judgment, traditional diplomacy is fixated on the immediate needs and health of the relationship with the ruling regime. The management of that relationship becomes paramount and sometimes, perhaps not always, overshadows long-term goals and values. That, very frankly, is something that concerns me a great deal about USIA’s integration into the State Department. I fear that the dominant priorities and impulses of traditional diplomacy – the management of today’s relationship with a particular government – will usually prevail at the expense of what we as a nation and a society really should be promoting. My State colleagues may view such sentiment as overly idealistic or unrealistic, but I sincerely think that clientitis is the most serious, endemic problem I’ve seen over the years in the Foreign Service.”

DELL PENDERGRAST: “There was certainly this sense both in the embassy and in Washington about the emotional, adventurous Poles pushing too far, about disrupting the equilibrium too much, that would arouse the Soviets. For an example, a constant irritant between the embassy and the Radio Free Europe in Munich was perceived bombastic language emanating from the Polish service of Radio Free Europe. It was never quite put so bluntly, but that was exactly what divided the exiles in Munich and the diplomats in Warsaw. I found myself personally in the middle, not necessarily adhering to either side. There probably was clientitis on one side and extremism on the other, which both made me uncomfortable. But the bottom line was that we saw the early impulses of communism’s fatal decline in the mid-’70s. And, it was, I thought, a perfect example of public diplomacy’s success, the triumph of the long- term cultural and educational and information approach that was having, over a period of time in a steady, deliberate way – a profound impact on these societies. And a lot of it was just personal contact by the embassy’s Polish-speaking officers, who circulated freely and actively in cultural and intellectual circles.”

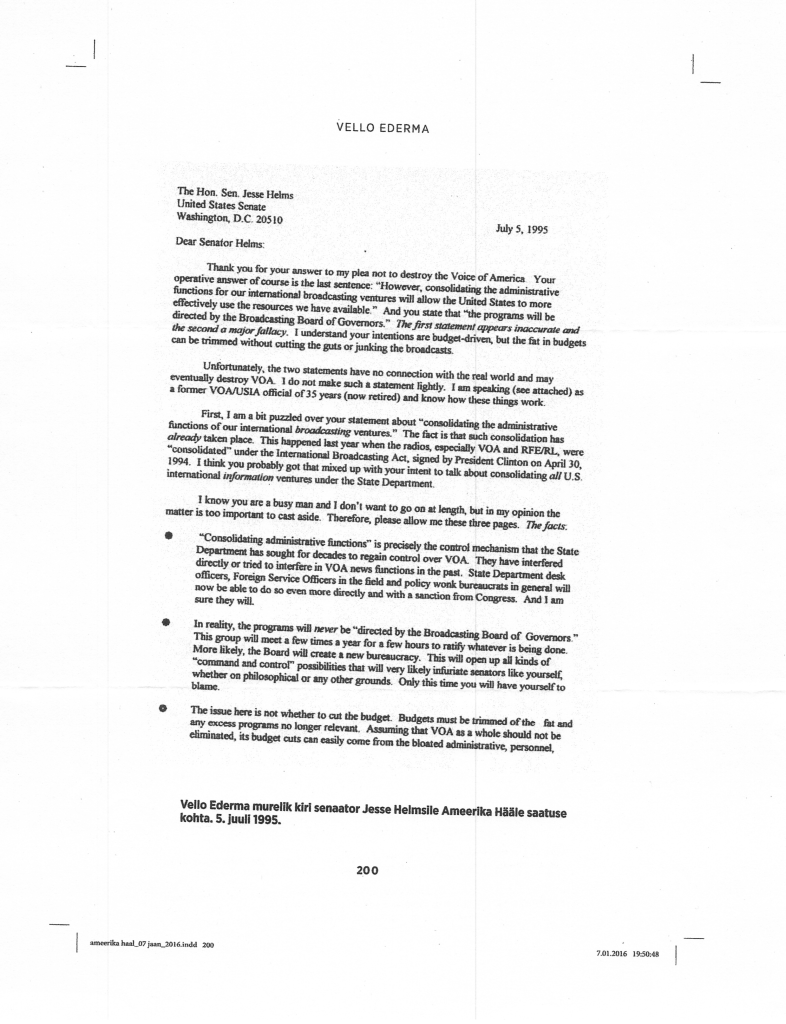

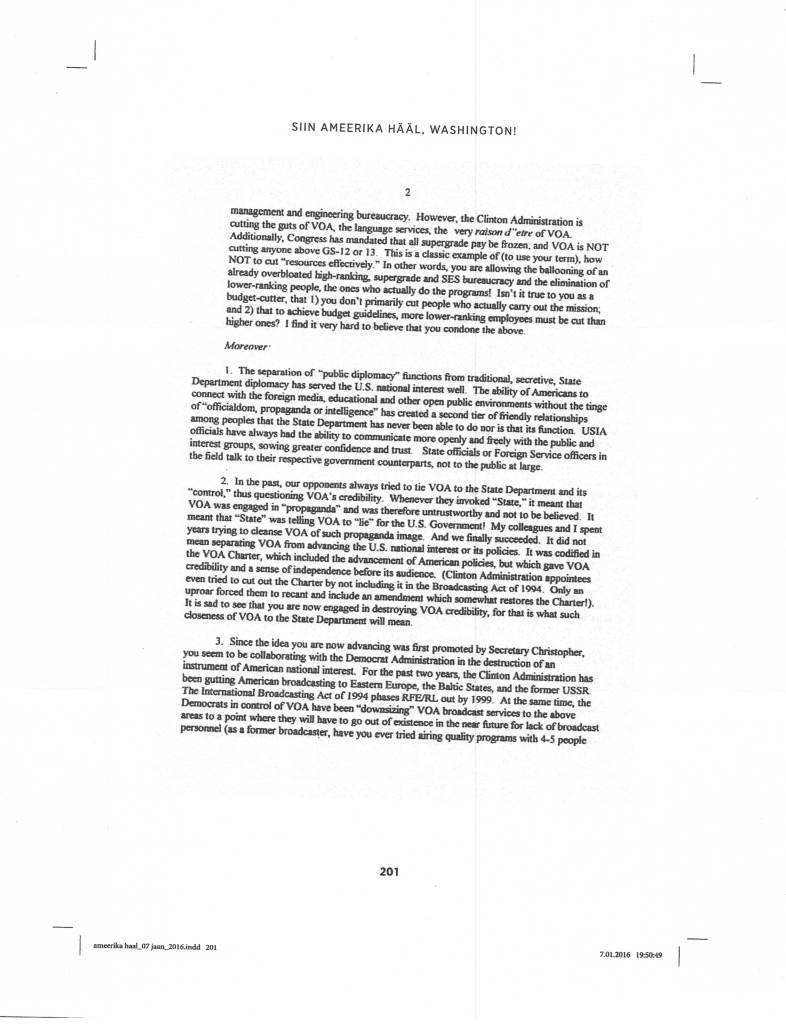

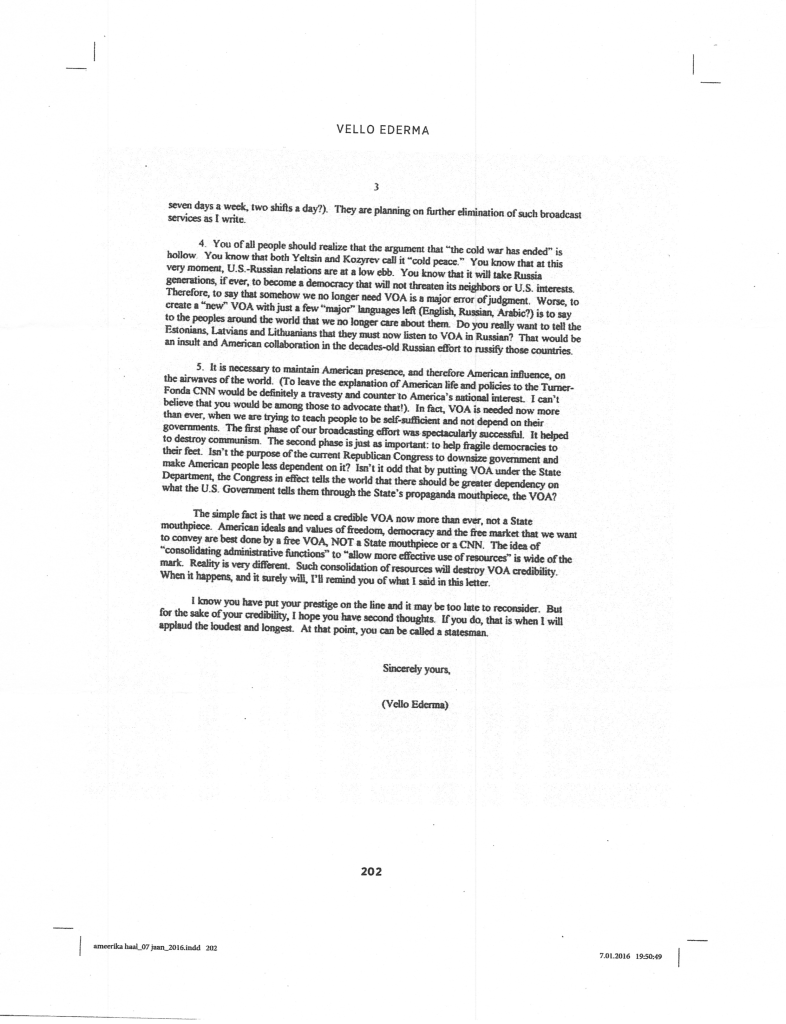

Vello Ederma was not a Foreign Service Officer. He is a former Voice of America (VOA) European Division Deputy Director and former VOA Newsroom editor. In a letter he wrote to Senator Jessie Helms in 1995, Vello Ederma predicted with remarkable accuracy the decline of both U.S. international broadcasting and U.S. public diplomacy as a result of the creation of the Broadcasting Board of Governors and consolidation of the United States Information Agency into the State Department. In 1995, Ederma was protesting Helms’ efforts in cooperation with the Bill Clinton Administration to eliminate USIA and move public diplomacy functions into the State Department. As the European Desk chief in the VOA Newsroom, Ederma had a major disagreement with the Polish Service chief, as in those days VOA language services were not supposed to carry sensitive target area news. Ederma changed that rule, arguing that if the Poles tear up railroad tracks in anti-regime protests, the VOA Polish Service has to carry such news. The Polish Service chief complained all the way up to USIA top echelon, but lost.

Encouraged by its ever-growing bureaucracy, the Broadcasting Board of Governors is again using “consolidation” arguments to resist structural reforms proposed in the bipartisan bill H.R. 2323 which attempts to undo at least part of the damage to U.S. international broadcasting and U.S. public diplomacy as a result of legislative changes in the 1990s which saw the abolishment of USIA and the consolidation of public diplomacy functions into the State Department.

VELLO EDERMA: Thank you for your answer to my plea not to destroy the Voice of America. Your operative answer of course is the last sentence: “However, consolidating the administrative functions for our international broadcasting ventures will allow the United States to more effectively use the resources we have available.” And you state that “the programs will be directed by the Broadcasting Board of Governors.” The first statement appears inaccurate and the second a major fallacy. I understand your intentions are budget-driven, but the fat in budgets can be trimmed without cutting the guts or junking the broadcasts.

Unfortunately, the two statements have no connection with the real world and may eventually destroy VOA.

In reality,the programs will never be “directed by the Broadcasting Board of Governors.” This group will meet a few times a year for a few hours to ratify whatever is being done. More likely, the Board will create a new bureaucracy. This will open up all kinds of “command and control” possibilities that will very likely infuriate senators like yourself, whether on philosophical or any other grounds Only this time you will have yourself to blame.

(…)

The separation of “public diplomacy” functions from traditional, secretive State Department diplomacy has served the U.S. national interest well. The ability of Americans to connect with the foreign media, educational and other open public environments without the tinge of “officialdom, propaganda or intelligence” has created a second tier of friendly relationships among peoples that the State Department has never been able to do nor is that its function. USIA officials have always had the ability to communicate more openly and freely with the public and interest groups, sowing greater confidence and trust. State officials or Foreign Service officers in the field talk to their respective government counterparts, not to the public at large.

(…)

The simple fact is that we need a credible VOA now more than ever, not a State mouthpiece. American ideals and values of freedom, democracy and the free market that we want to convey are best done by a free VOA, NOT a State mouthpiece or a CNN. The idea of “consolidating administrative functions” to “allow more effective use of resources” is wide of the mark. Reality is very different. Such consolidation of resources will destroy VOA credibility. When it happens, and it surely will, I’ll remind you of what I said in this letter.

Almost every prediction Vello Ederma made in his 1995 letter to Senator Jessie Helms turned out to be true.

We are seeing history repeating itself for an even worse outcome in 2016 with BBG bureaucracy’s and leadership’s efforts to achieve an even greater consolidation of the agency and resisting bipartisan reform efforts through H.R. 2323 legislation.

Carl A. Bastiani was Principal Officer at the U.S. Consulate General in Krakow (1979-1983). Mr. Bastiani was born and raised in Pennsylvania and educated at Seminaries in Iowa and Illinois and at the University of Chicago and Georgetown University. A specialist in Italian and Romanian affairs, Mr. Bastiani served at four posts in Italy (Naples, Genoa, Rome and Turin) and in Romania and Poland. He also had several tours of duty at the State Department in Washington, DC. Mr. Bastiani was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in 2008.

CARL BASTIANI: “They were getting the news and they were listened to [Voice of America and BBC]. However, Radio Free Europe, RFE, was really the best at this. They used to get local news from people in Poland like Reuters and Associated Press gets theirs world-wide from stringers. RFE was broadcasting it to the Poles like a local network. They had great credibility and were very much listened to. RFE played the role in Poland of the voice of a responsible opposition in a democratic country, exposing the shortcomings of the powers that be. And that’s why the regime’s misinformation was not believed by most Poles. Because of VOA and the BBC as well, but they focused more on presenting the views of the West and what was going on in the rest of the world.”

John W. Shirley was Public Affairs Officer, USIS Warsaw (1970-1971). He was born in England to American parents in 1931. He graduated from Georgetown University in 1957 and served in the U.S. Air Force overseas from 1954 to 1956. After entry into USIA his postings abroad have included Yugoslavia, Trieste, Rome, New Delhi, and Poland, with an ambassadorship to Tanzania. Mr. Shirley was interviewed in 1989 by G. Lewis Schmidt.

JOHN SHIRLEY: “Let me generalize for a moment.

I think that the Agency’s work in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union — and I very much include the work of the Voice of America — was in every respect more important than anything we did anywhere else in the world. Throughout the 40 years of Soviet domination it was we — “we,” USIA; “we,” VOA and Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty, the BBC, and Deutsche Welle – – who kept alive in the peoples of those countries the hope that someday things would change and that the West cared.

Not only was it a matter of providing information, but also of sustaining their hope by letting them know that we cared enough to broadcast to them, to have exchange programs with them, to show them exhibits, to talk to them as individuals, to send professors to their universities, to open libraries in which they could spend happy and profitable hours. A dollar spent in Eastern Europe was worth a thousand dollars. A dollar spent in many other parts of the world was worth $10.00 or $1.00, and sometimes only 50 cents.”

Ambassador Nicholas A. Rey was U.S. Ambassador Poland (1993-1997). He was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1938 before moving to the US. He attended Johns Hopkins University, and went on to serve in the Treasury Department. He was appointed Ambassador to Poland in 1993. He was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in 2002.

AMBASSADOR NICHOLAS A. REY: “USIS was also party to the single most ironic event, among the many Polish ironies, that I witnessed. This was the return to the Polish Archives of copies of tapes of all the Radio Free Europe Polish Service Programs. This is the single best source of the “Truth” of what happened in Poland during the Cold War. The Polish Archives are a subsidiary of the Ministry of Education and the Minister accepted the tapes on behalf of Poland at the official ceremony. The Minister was Jerzy Wiatr, who in the 1980s Communist Government had been Minister of Propaganda. At the celebratory luncheon, he actually had the gall to tell Jan Nowak (Who had been the head of RFE’s Polish Service for many years) and me that the only difference between that old government and us was the question of timing [of when the change to democracy should occur].”

Chester A. Opal was Information Officer, USIS Warsaw (1946-1949). He was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1918. He attended the University of Chicago. He began his Foreign Service career in 1946. His career included positions in Poland, Italy, Lebanon, Mexico, Austria, Vietnam, and Washington, DC. In addition, Mr. Opal helped to found the NATO Information Service (NATIS). He was interviewed by G. Lewis Schmidt in 1989.

CHESTER A. OPAL: “Of the USIS program itself, I have no idea whether it was effective. We felt that our chief purpose was to establish the fact, one, that we had not forgotten the Polish people. And two, that we had our eye on the regime and we knew what was going on and if the boom ever fell we would know what the situation was. As part of this awareness program, I started a daily cable which we sent from Warsaw to Washington, in which I reported on the weather in Warsaw, for example, or tell of men who were now walking the streets with their little party buttons on their lapels so the secret police wouldn’t bother them or in anyway frighten them. It was little items like this that I would report to Washington and they would come back over the Voice of America as a regular broadcast of news.

This was intended to show to the Poles that we had eyes everywhere in Poland, we knew very well what was going on in that country and the regime wasn’t going to get away with anything.”

CHESTER A. OPAL: The one thing I do want to say something about is the importance of the Voice of America in Poland. We used to broadcast–it was not jammed at that time–and I have mentioned the cable that I used to send and the other items that they would pick up from our reports from the post. One thing that didn’t occur to me then but should have been evident, was something that I brought out in Vienna in ’53 at a meeting that was conducted by Chris Ravndal, who was the Minister to Hungary. At the time we were discussing Voice of America policy and there was an awful lot of discussion of the reputation of BBC for fairness and how we are thought not to be fair and unprejudiced.

I listened to this for almost a day as they went around the table and I had no real interest in the Voice because of the post that I was at, which was Vienna. But I said, ‘I served behind the Iron Curtain and I can tell you there are people who sit in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, who will turn on Radio Ankara and Radio Madrid, every morning of their lives to hear that there is going to be a revolution in their country and that they are going to be liberated the following day. Now nothing occurs to this society they inhabit, but the next morning they turn on Radio Ankara and Radio Madrid because they want to hear how they’re going to be liberated the next day and they’re going to be free men. Nothing happens that day and the following day they do the same thing. Their temperament demands it.’

‘There are people in these countries and in Poland, which I can speak for, who listen to Voice of America and who listen to BBC. BBC was the channel by which they received their instructions from the government in London and by which they sent instructions from one sewer in Warsaw to London, back to men in another sewer in Warsaw, during the uprising of ’44. Britain had a reputation then for being sympathetic with the Poles, they had gone to war because of the invasion of Poland in ’39 and therefore, it was fine.’

‘Their feeling about Britain, that it was neutral in its broadcasts, is, I think, an index of the proportion of assumed British involvement. Britain no longer controlled their destiny and I think if you will go around the world and find out where the British are still exercising power one way or another, the people will say that they are not neutral to the degree that they exercise actual or potential power.’

‘The Poles believe that we have power in the world, therefore, everything we say has some meaning in relation to our power. The British no longer have any power; therefore, they can be neutral. And whether they are neutral or not they are going to be thought to be neutral because, what is the point of their not being neutral? They don’t control power, they don’t have the capacity to free these people or to oppress them or anything else. Therefore they exist out there and since they are not as incendiary as Radio Madrid or Radio Ankara, they are obviously neutral. The America does exercise power. It is the dominant power in the world’–this was in 1953 remember–‘and therefore the assumption is that the Voice of America is implementing this power, one way or another, either actually or potentially. Therefore, it can’t be neutral. I say I don’t know why we exercise ourselves over this question.’

I carried this idea to Washington later and to Henry Loomis when I wrote a charter for the Voice of America. This was the thing that I brought out in Beirut, that I remembered yesterday, that struck Director Leonard Marks. Because there still is this concern about the British neutrality and BBC objectivity. I don’t care how much we try to present it but I think we should be true to ourselves, be true to our own ideas of truth and honesty. I think we should do this and we should hold to this. But we shouldn’t worry about imitating the British and their kind of ‘objectivity’ because we will never pull it off. Until we arrive at the British world position which is nothing now. This was the point that I made.

Apparently the point had some effectiveness because the meeting in Vienna in 1953 immediately disbanded and we had no further discussion. I remember someone said, ‘I don’t know how he got into this meeting but he sure messed it up.’ At any rate, I still believe this. I believe that as long as we’re thought to have some influence and power, our ‘voice’ and everything we do will be thought to be prejudiced in favor of our power and it’s natural for people to make this assumption. I don’t think we should worry about that. We should, as I said, be as true to ourselves as we can, which is what I said in my culture paper too. Be true to ourselves and not worry about the impression we make because we cannot think for others and then try to outthink them because you wind up at the same place anyway, which is with yourself and that’s what you have to live with.”

Ambassador John D. Scanlan was Consular/Political Officer in Warsaw (1961-1965). He was born 1927 in Minnesota. He served in the Navy in World War II and attended the University of Minnesota. He joined the Foreign Service in 1955. His postings included Moscow and Warsaw. He was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in 1996.

AMBASSADOR JOHN D. SCANLAN: “We were undermining the Polish communist system by keeping creative Poles in touch with cultural developments in the United States, keeping them informed. This was the period when the Soviets were trying to keep information out of the Soviet Union and to some extent out of Eastern Europe. They were not that successful with regard to Eastern Europe. They spent more money jamming the Voice of America than we spent broadcasting. You can hear the jammers even in Poland. But Radio Free Europe got through even though the Poles had a jamming program, too. VOA did. We were getting information into Poland and through Poland into the Soviet Union. It was a very successful program in many ways. For instance, we sent so many Polish scholars of sociology to the U.S. in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s under a Ford Foundation program and under other programs that we helped develop a very good school of Polish sociology. They put out a quarterly publication on sociology which was excellent. I recall being told by some of these Polish sociologists that their Soviet colleagues told them that they had to learn to read Polish. They could get the Polish quarterlies. They couldn’t get the American quarterlies.”

Q: I would think that one of the greatest tasks that you might have been faced with was the death of President Kennedy. Were you there?

AMBASSADOR JOHN D. SCANLAN: Yes. John Steinbeck was there at the time. He had been at that famous dinner at the White House with all the Nobel laureates where Kennedy said this was the greatest collection of wisdom at dinner since Thomas Jefferson dined alone. In any case, Steinbeck on that occasion was approached by Kennedy to go to Eastern Europe. He went to 3 countries, Yugoslavia also. I had been his escort in Poland most of the time including the day that Kennedy was shot. We went down to Lodz. He had been in western Poland, where he had been taken care of by our Poznan consulate staff. Then they delivered him to Lodz, the second largest city in Poland. There was a university there and he was going to speak to the American literature program students. We were there with him for that. They gave a dinner for him. Then we drove him back to Warsaw. He was with his wife, Elaine, and we were in my car. My wife was there. He was kind of tired. He had been in Poland for a week and had had programs every day. He didn’t want to do anything that evening. We said, “Would you like to come back to our house and have just a simple spaghetti dinner?” He said, ‘That would be wonderful. I’ve had all this heavy Polish food.’ So we had a nice, quick spaghetti dinner at our house. Then I took him to his hotel. I dropped by the embassy then because I had been gone all day. It was about 8:00 PM. I walked into the embassy and went back to the press and culture section and saw the press officer, Phil Arnold, working with the ticker. He said, “Jack, President Kennedy’s been shot.” We didn’t have rapid communications in those days. So, we were getting a report on VOA. I said, “I’d better tell Steinbeck.” I called the hotel and the maid on their floor had just told them but they had nothing further. So, I said, “Well, I’ll come by and bring a portable radio.” “Yes, please do that. I’m very concerned.” So, I dropped by my home first to tell my wife what was going on. While I was home briefly, the desk officer, the second or third guy on the Polish American desk in the foreign ministry, came to my door to express his condolences and his personal grief. This guy was a communist official from the foreign ministry, a very nice guy. Unfortunately, he died fairly young, Andrzej Wojtowicz. He was later posted in Washington and was quite popular here as a Polish diplomat. That was the nature of the society. The Poles took this almost as a personal loss. So, I went back to the hotel. Steinbeck was in his pyjamas and bathrobe and Elaine was there, very upset by this. We didn’t know what had happened, who had shot him. It was a horrible feeling. We were cut off from the world, listening on VOA and static and what have you. We were getting the reports. Elaine was from Texas and was a personal friend of John Connaley, who was also shot. They had been in Texas just before coming on this trip and had heard all of this violently anti-Kennedy stuff from some of the wealthy Texans. I think Steinbeck at that point was almost prepared to believe that this could have been a plot by some of these violently anti-Kennedy Texans.

Terrence Catherman was a USIA Foreign Service Officer and served as Voice of America, Deputy Director in Washington, DC in 1983. He was born in Michigan and attended the University of Michigan in the early 1940s prior to joining the army. He completed his bachelors and master’s degrees in political science. He joined the Foreign Service and received his first post in Tel Aviv, Israel. His Foreign Service career also took him to Germany, Russia and Yugoslavia. He was interviewed by G. Lewis Schmidt in January 1991.

TERRANCE CATHERMAN: “Toward the end of that first year and a half in Washington, the Poles began their clamp down. USIA responded, as did the US Government, of course, with approbation, and the Poles began jamming the Voice and I was sent down to the Voice of America as Deputy Director in a period when the Voice was once again beginning to occupy center stage because in that crisis people were looking to the Voice as a source of information, and as a source of broadcasting official commentaries on world affairs. So it was exciting.

The Voice is always in a turmoil. It is right now. We are in another crisis here.Q: Yes, a little later I would like to get your thoughts on the most recent attempt on the part of the Agency to pull the Voice’s personnel and their budgeting back into the central office.

CATHERMAN: Yes, I was, of course, in the Voice of America when Mr. Wick gave VOA autonomy over the conduct of its personnel and administrative offices. And now I am back at the Voice, working as a retiree, when the opposite move is being made. So I have seen it go both ways. If I may comment right now on that, I think Mr. Wick was very wise to do what he did because he won the loyalty of the directors of VOA in giving VOA some autonomy in conducting its personnel affairs. USIA had never done a very good job of administering VOA. For one thing USIA has other interests and VOA has only one and that is broadcasting. So, USIA tended to apply different criteria in its hiring policies than VOA wanted to apply. VOA needed broadcasters. USIA needed foreign service officers, writers, a variety of people, cultural affairs specialists, etc. and did not concentrate adequately on getting broadcasters for VOA. So I think that was a very wise move on Mr. Wick’s part. In return he had very good relations with the directors of VOA. In a way I thought they felt they were beholden to him for that move. Another thing that Mr. Wick did in that period when I was here was commence an enormous rebuilding of the VOA broadcasting infrastructure. There was a time when people were talking in terms of putting upwards of a billion dollars alone in VOA construction. That has since eroded.

Q: It was pretty much brought up sharp about four or five years ago.

CATHERMAN: But those were heady days down here. They were ideologically fraught. I came down here at the same time that some very extremely right wing ideologues also arrived in the Voice of America. The editorials they tried to write I thought were so full of anti-Soviet invective that they did not properly represent official American attitude towards the Soviet Union, nor were they proper content for VOA broadcasts. I had quite a struggle on that one. As a matter of fact, I think eventually I was eased out of the Voice because of my obstreperousness in protecting the VOA news service from that kind of influence and in trying to temper the political content.

Q: What was your observation of the feeling of the rank and file of the VOA personnel at that time? Were they also disturbed by this heavy orientation towards the extreme right wing.?

CATHERMAN: Well, they were outraged. That is an element of VOA was outraged. Another element of VOA was outraged that we were not harder. That is endemic to VOA. VOA has elements that will be outraged at whatever happens. It is a huge amorphous group of people. There are all kinds of elements down here as there must be because we are an international broadcaster. We have all these language services and we also have a determined core of American journalists who consider themselves journalists and are going to defend the First Amendment, as any right thinking journalist would do. All kinds of people down here encompassing the political spectrum.

Q: Do you still have bad feeling between the English language broadcasts and the other language services?

CATHERMAN: Sure.

Q: Still as tough as it ever was?

CATHERMAN: I think that that sort of back biting here in the Voice has subsided somewhat, but it has not disappeared. It is not as rampant as it seemed to me it was when I was here 10 years ago. I think part of that is the soft touch of the administration of the Voice right now. The people who are running the Voice are very attuned to the various tensions here and pay attention to them, and don’t fan the flames. Which has been done in the past.

Q: I headed, at the request of then Director Jim Keogh, a study group that came down here in ’74 and it was rampant at that time. The battle of the English language broadcasting which felt it was riding high was the principal element of the Voice and the opposition, the language services which was terribly intense at that time.

CATHERMAN: This came to the fore again, of course, just recently when Mr. Gelb came over here and insisted on appearing before the employees of VOA together with Mr. Carlson. In the process it seemed to me at any rate, some sores in VOA were reopened. It is not merely that VOA has an intense relationship with the mother agency, but it also has all of these things going on within VOA. All of those lesions were opened again. So the tension is bigger than it was, let’s say four or five weeks ago. But it still is not as big as it was in those days when the Poles were jamming and a new administration was trying to figure out what to do with the VOA and there were all those political uncertainties. We do not have those political uncertainties here in the Voice right now. We know where we stand and we know how to deal with it.”

John P. Harrod was Public Affairs Officer, USIS Warsaw (1984-1987). He was born in Illinois in 1945, and received his BA from Colgate University. Having entered the Foreign Service in 1969, his positions included Moscow, Kabul, Poznan, Warsaw and Brussels. He was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy on March 1, 1999.

JOHN P. HARROD: There are some things that emerged in my subliminal consciousness while we were there. One was the importance of television and video material. At the beginning, what we did was we invested a lot of money in multi-system VCR equipment, meaning it could play both European and American tapes. And then we loaned these VCRs out to various institutions on long-term loan from the U.S. embassy. Most of these institutions happened to be Church- or Solidarity- related cultural groups, and then we could funnel American videotapes to them, and they could use their equipment. We essentially had a wide distribution network around Poland using video, which is something that I hadn’t done in previous assignments. Toward the end of my time there, my press attaché, Paul Smith, found that one of his neighbors had a satellite dish and was pulling in CNN and Worldnet and these other things directly into his house, and so we invested in a satellite dish – Paul bought it personally, but we reimbursed him for it – and he set it up out at his house, and we started pulling in Worldnet and bringing the tapes to the embassy and showing them in the Cultural Center in the theater every day. And the Poles shortly thereafter tried to put in a law about controlling satellite dishes, even though there was a Polish entrepreneur, I think, up on the Baltic Coast who was making satellite dishes and selling them. The Poles finally put a hold on their law and said they were going to study it for a year or so, by which time there were so many satellite dishes around Poland there was nothing they could do about it, which I think was their intent all along. We can’t regulate this. But both of these things struck me with the power of direct communication, which is something I hadn’t been able to do in Moscow, where people listening to the Voice of America in crackly, bad reception in the middle of the night was about as close as you could really get. With the videos and particularly with direct satellite broadcasting, you could reach people almost instantaneously and directly and bypass government control. It was quite an impression.

Q: What type of things were you distributing on your VCR tape net?

HARROD: A lot of things that USIA would be distributing to us, some of them commercially available products in the States about U.S. culture, American films, but also when USIA would send out tapes about specific policy kinds of issues, whatever they might be, we could loan those out as well.

Q: Were they put into Polish, dubbed, or were they-

HARROD: Most of it was in English. But there was a wide knowledge of English in Poland, and in some cases we could get them translated if we needed to. We also were doing things, one of the indelible memories I have which kind of illustrates this strange situation in Poland at the time, there was a higher educational institution called, let’s see, the Higher School for Planning and Statistics – SGPiS, in Polish – which was sort of their Wharton School, the highest level of economic and foreign trade education they had, and it was right in Warsaw. One day a couple of students from there came to see me at the embassy. We didn’t get a whole lot of callers, but they came in and they said that there was a week of Soviet culture that had been organized out at SGPiS by the officials – a week of, you know, Soviet film, dance, song, whatever – and they thought it would be fair to have a week of American culture to balance it out. And this was probably ’86, when things were still a bit dicey, and we had some people PNGed from our embassy, so it was still a little iffy. And I said to them, “Do you really think you can do this?” And they said, “Yes, we think we’ve got enough support to do this.” And so we entered into an arrangement, and we began to work with them, and we put together a week-long program that involved lectures, films, the whole week of American culture. And they got the support of their institution to do this. The one sticking point is we needed a fairly large hall for the opening session. We were going to have some talks, and we had a visiting speaker. We needed a fairly large room. And it was exam week at the school, and so most of the large halls were being used, so the students went to the head of the ROTC program, a colonel in the Polish army, and asked if they could use the ROTC hall. And he said “Sure.” So to open the week of American culture at this institution, I was up on the podium along with the colonel in his full military rig and other officials from the school, and we had our week of American culture. Strange.

I mentioned PNGs, too. We had three people thrown out of the embassy while I was there, one of them a USIA officer. I almost got thrown out of the embassy. What you had was a sense of various forces kind of struggling within Poland at the time, from the opposition to the more moderate folks in the régime to the real hard-liners maybe on one extreme.

Willis Conover, a Voice of America program host, was not a Foreign Service Officer or a USIA employee. His preference was to work for VOA as a contractor. There were relatively few contractors working for VOA during the Cold War. They were subject to nearly the same strict recruitment and security procedures. Under BBG’s management today, the agency employs hundreds of poorly-paid contractors, many of whom were hired by BBG managers in violation of federal government rules and regulations.

Willis Conover was Voice of America’s “Music USA” program host when he made a trip to Warsaw in 1959. He was born in New York in 1920 into a military family and served in the US Army abroad in World War II. An amateur vocalist, he became a popular disc jockey in Washington, D.C. and later joined the Voice of America. Specializing in American jazz, his programs were immensely popular abroad, particularly in Russia and Eastern Europe. The Conover name became a symbol of American jazz at home and abroad. Mr. Conover died in 1996.

Q: Is that the way the Polish program is handled today?

WILLIS CONOVER: Actually, the program that I do to Poland today is done somewhat differently. I do the program in the studio, in English, and with music, onto tape. The tape is given to Renata Lipinska – that’s her broadcast name. She edits the tape and makes a script, which transcribes that part of what I say that has been kept on the tape, and also puts what she is going to say in Polish onto the script, and it goes back and forth the next day. I am in the control room with the engineer, she is here in the studio, and we each have a copy of the script, and we go back and forth between me (and the music) on tape and her on microphone onto still another tape, and that is what is broadcast. It’s just a slightly different way of doing it.

Q: Back to the fifties. What were the early signs of success for the program, aside from Marie finding somebody who asked about you at an exhibit?

CONOVER: Well, the early signs of success were letters from a number of different parts of the world, including the Soviet Union – not as many as there were listeners because it wasn’t that easy for people to write to someone at the Voice of America in Washington from anywhere in the Soviet Union. Then there were also articles appearing in newspapers in other countries about the program.

And I must say that when it was decided that I should go to meet my listeners in a number of different countries, I got my itinerary and announced on tape, on programs to be broadcast while I was traveling, where I was that day, where I would be the next day, and where I’d be going the next day, and so forth. The most unforgettable experience of that first trip, in 1959, was my arrival at the airport in Warsaw, Poland. Looking out the window of the plane when we landed, I saw at the foot of the ramp some people with cameras, people with tape recorders, some little girls carrying flowers, and a big crowd behind the airport fence. I thought, Well, I’d better wait till whoever that’s for gets off, and I was the last person off the plane. And that’s when the cheering started from behind the fence. It was for me. They had heard me say on my program that that was when I was going to arrive.

I was met at the ramp and handed the flowers, official Polish flowers, picture taken, tape recorder, Radio Warsaw welcoming you to Poland, etc., and a representative of the United States Information Agency, who was in the American embassy there, also met me. We came out of the terminal, all these people surrounding me, and a band started playing, 20 or 30 musicians. We got into the embassy car, driving into town, and people were bicycling and motorcycling alongside the car and waving at me inside, and I said to the USIA representative, “What is going on here?” He said, “Tonight and tomorrow night musicians are coming from all over Poland, at their own expense, to perform for you at the National Philharmonic Hall, to show you what they’ve learned from your broadcasts.”

This was incredible. I was introduced from the stage – I was sitting in the front row with a bunch of people – the place was absolutely packed – introduced from the stage, and the applause went on so long I rose to acknowledge the applause but it went on even after I’d sat down, so long that I finally had to get up on stage and say something myself.

Gifford D. Malone was Consular/Economic Officer in Warsaw (1961-1963). He was born in Richmond, Virginia and entered the Foreign Service in 1958. His career included overseas posts in Warsaw and Moscow. Malone’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on December 5, 1991.

GIFFORD D. MALONE: “After all the press was controlled. They listened to Voice of America and Radio Free Europe…I suspect the majority listened. It wasn’t jammed in Poland. You combine that with the fact that the ordinary citizens all hated the government, this was evident in the atmosphere even though people didn’t come out and say that. One felt a certain constraint and a certain amount of tension.”

GIFFORD D. MALONE: “One day my wife and I were sitting in our kitchen having breakfast listening to the Voice of America. The announcer said, ‘An American Foreign Service officer had been arrested.’ I remember thinking to myself, “I wonder if that is anyone I know?” It was Scarbeck. It was the first time I ever saw my wife’s jaw literally drop. We looked at each other. He had done a lot of foolish things and been entrapped in a rather classic way by the secret police. They claimed they would do terrible things to this woman with whom he had become involved if he didn’t give them materials, so he did give them some stuff.”

Q: That brings us to your next assignment which was going to USIA from 1973-75. Was this a normal assignment for a State Department officer to go to USIA?

GIFFORD D. MALONE: No it wasn’t. It had never occurred to me that I would work in USIA, although I think by virtue of the fact I had worked in Soviet Affairs and Eastern European Affairs I had worked quite closely with USIA. Even in Moscow when I was more junior I would sometimes go on trips with visiting American writers, or something at the request of USIA. So I had had experience working with them earlier. When I was in SOV, actually, part of my portfolio was being the liaison person with USIA. So I was frequently on the phone with the people at Voice of America, or going over to meetings at USIA, etc. So, having had this experience in Poland and having worked very closely with the Public Affairs Officer, the chief of USIS section, when he invited me at the time I was leaving Poland to come over to USIA for a tour, it seemed, although not the usual thing to do, to be a sensible and interesting thing to do. And so I did it.

S. Douglas Martin was Chief Economic Officer in Warsaw (1964-1967). He was born in New York in 1926. During 1945-1945 he served overseas in the US Army, upon returning he received his bachelor’s from St John’s University in 1949 and later received his law degree from Columbia University in 1952. His career included positions in Germany, Washington D. C., Yugoslavia, Poland, Laos, Austria, Turkey, Nigeria, and Cameroon. Mr. Martin was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in January 1999.

S. DOUGLAS MARTIN: When Gronouski arrived, his wife was afraid of flying, so they came over by ship. And there was a lot of stuff about him, because he had been a member of the cabinet, the postmaster general. He was pushed aside to make room for O’Brien.

Q: Larry O’Brien?

S. DOUGLAS MARTIN: Larry O’Brien, who was a political operator, and Johnson wanted him when he was going to run for President and to make sure he had a postmaster general who could help him politically. He didn’t have that much confidence in Gronouski.

Gronouski had become ambassador almost by a fluke. There was another better candidate who was more Polish, but who didn’t have a Polish name, so Gronouski, who was really not conscious of being a Polish-American so much but had a very Polish name, he got the job. Kennedy picked him because it was good politically. Johnson sent Gronouski to be ambassador to Poland but also he wrote a letter. He tried to elevate the job by saying that he wanted to have Gronouski’s opinion on a regional policy toward Eastern Europe. So he was making him kind of an ambassador for Eastern Europe, not just Poland. All the other ambassadors, Outerbridge Horsey, but also Elam O’Shaughnessy in Hungary, all took a dim view of this.

Gronouski had to come by surface. So he went by ship to Paris and by train to Vienna, and then we sent somebody to meet him there because we thought he might need help. He didn’t know any foreign language at all, never studied a foreign language, never even studied Latin. We sent an Agency guy out, a friend who spoke Polish fluently. He saw Gronouski was standing there, looking at this absolutely desolate Polish countryside – I mean, snow-covered ground and freezing cold and just desolate – and he looked at it for a little while, and not looking at the guy, just out loud, he said, ‘Lyndon, you son of a bitch! What have you done to me?’

He immediately started trying to learn some Polish, but if you’ve never studied Polish and you’re 50 years old, you’re not going to learn much. We had the presentation of credentials, and under the Polish system they have this military tradition and they have a military honor guard out there, they’re at order arms, about going to present arms. The ambassador is supposed to say, “I salute you,” in Polish, “I salute you Polish soldiers or something.”

It goes something like zolnierz ponoszczi. So when they went to present arms, he said, ‘Zolnierz . . . ‘ and he froze. About 30 seconds went by. He had been practicing it so long. And finally it came out, “. . . ponoszczi.” And then the arms came down from order arms to present arms. He was returning their salute.

He wanted to make a speech in Polish over Voice over America, and he did, but it was done with a tape recorder where he would memorize three words, and he would say those three words and then they shut the machine off. And then they’d practice the next five words. They’d go through the five words. So he made a speech over Voice of America, abut it was a technological feat and an achievement of modern technology; it was not a speech in Polish by somebody who knew any Polish.

John H. Trattner was Press Attaché, USIS Warsaw (1966-1968). He was born and raised in Virginia and was educated at Yale, Columbia and American University. Joining the United States Information Service in 1963 he worked first with the Voice of America, and then was transferred to Warsaw as Press Attaché. His subsequent assignments all in the press and information field include Strasburg, Paris, Brussels, and Washington, D.C., where he served as assistant to Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher and finally as official Spokesman for the Department of State. Mr. Trattner was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in 2007.

JOHN H. TRATTNER: “Poles whom we knew and mingled with often expressed pleasure that the Americans, for a change, had sent them a Polish-American ambassador. In 1968, when Johnson announced his decision not to run for re-election, it fell to me to relay the news to Gronouski. It was very early in the morning, and I got the word by telephone from our agricultural attaché who said he had heard it on the Voice of America. Since the Johnson decision would have impact on Gronouski’s own future, I called him at home right away. His wife answered in a sleepy voice and put the ambassador on the phone. After listening to what I told him, he asked in a somewhat stunned voice if I was sure. I replied that this was what I’d been told, and repeated what the source of the information was. “Well,” Gronouski growled, “you damn well better be right.” I spent the next several hours very much hoping the attaché had heard correctly.”

Lawrence I. Plotkin was Assistant Cultural Attaché, USIS Warsaw (1974-1976) and Branch Public Affairs Officer, USIS Poznan (1976-1977). Lawrence I. Plotkin was born in Chicago, Illinois and raised in Southern California. He attended the University of California at Los Angeles and joined USIA in 1973. His posts included Poland, Panama, Washington, DC, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria. Plotkin was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in 2004.

Q: “What were your impressions about what the Poles were learning about the United States and American studies?”

LAWRENCE I. PLOTKIN: “There was an enormous amount of interest in the U.S., and almost everybody listened to or tried to listen to Voice of America and other Western international radio broadcasts. The best known American in Poland was VOA’s Music USA host Willis Conover. We knew that if they were listening to him they could and almost certainly would listen to VOA broadcasts of news of the world and news of Poland on RFE.

In addition, public interest was shown by the crowds at our public events. Concerts and exhibits drew large audiences. Those were the days of major U.S. exhibits including, in 1976, the U.S. bicentennial exhibit that toured just four European cities, Warsaw, Rome London, and Paris. One room in the exhibit was dedicated to honoring the involvement in the American Revolution of citizens of each country in which the exhibit appeared. In Warsaw, it was focused on Polish American relations with emphasis on Generals Thaddeus Kosciuszko and Casimir Pulaski. There were huge crowds of course.”

Richard A. Virden was Information Officer and Press Attaché in Warsaw (1977-1980). He was born and raised in Minnesota and educated at St. John’s College in Collegeville, Minnesota. He joined the Foreign Service of the United States Information Service (USIA) IN 1963 and served variously as Information, Press and Public Affairs Officer, attaining the rank of Deputy Chief of Mission in Brasilia. His foreign posts include Bangkok, Phitsanulik and Chiang Mai in Thailand; Saigon, Vietnam; Belo Horizonte, Sao Paulo and Brasilia in Brazil; and Warsaw, Poland, where he served twice. Mr. Virden also had several senior assignments at USIA Headquarters in Washington, DC. Mr. Virden was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in 2011.

RICHARD A. VIRDEN: “In terms of getting news from the outside world, we were pretty cut off. We’d receive the International Herald Tribune three or four days after publication. Voice of America and BBC were important to us in those days. They came in by short wave of course and there were sometimes efforts to try to jam them, but most of the time that didn’t really work and we were able to hear them.”

RICHARD A. VIRDEN: “The bitter economic conditions clashed with the lies that the government was telling about how wonderful their worker’s paradise was; ordinary citizens could clearly see that the reality of everyday life was very different from what the government was claiming.

As a result, the government and party had lost all credibility by this stage. We’re talking more than thirty years, now, that this system had been in place, and people no longer believed what they heard.

The government did have a monopoly on broadcasting, except for things like Radio Free Europe or BBC short wave radio from outside the country. But what Poles were hearing from their official mouthpieces was contradicted by what they actually saw every day when they went out into the streets and stores.We talked about a credibility gap in our own country during the Vietnam War. Well, this is what prevailed in Poland in those days.”

Walter K. Schwinn was Public Affairs Officer, USIS Warsaw (1946-1949). He joined USIS after serving as a colonel in an economic intelligence unit in World War II. His career included assignments in Poland, Malaysia and Saudi Arabia. Mr. Schwinn was interviewed by David Cartwright on June 24, 1987.

Q: “Well now, as someone in the information business, how did you respond to this deepening chill in relations? What did you try to do about it, anything?

WALTER K. SCHWINN: Well, just tried to keep going, keep the library operating, keep the Polish bulletin being distributed…. One of the more important duties of the staff was to brief the Voice of America on a, sometimes on a daily basis as to what would be suitable for broadcasting in. You just tried to keep going, that’s…. And I must say that we never lost touch with the library entirely. That was our best measure, visible measure, was that there were still Poles who, despite the chill, would be willing to keep coming in. But most of them were older, older persons who had less and less to lose.”

Cecil B. Lyon was Consular Officer in Warsaw (1948-1950). He was born in New York in 1903. He graduated from Harvard University in 1927. Mr. Lyon joined the Foreign Service in 1930. His posts included Cuba, Hong Kong, Japan, China, Chile, Egypt, Poland, Germany, France, and Ceylon. He was interviewed in 1988 by John Bovey.

CECIL B. LYON: “There was one man in the Foreign Office who was comparatively friendly. When Elsie was ill and had to leave, he said, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry to hear your wife is ill.’ Those are the only kind words that any official Pole said to me in two years. We got one message while we were there which was rather disconcerting, from Elsie’s father. It said, “The man whose wife is an artist has asked me to be head of Radio Free Europe.” The man was Dean Acheson — Mrs. Acheson is an artist, as you know. And the Poles eventually found out about this and they said, ‘Oh, your father-in-law is trying to help form a government to take our place, isn’t he?’ It didn’t make us feel too comfortable.”

Henry A. Cahill was General Service Officer Warsaw (1961-1962) and Political Officer Warsaw (1963-1964). He was born and raised in Manhattan until the age of twelve when he and his parents moved to Boston. Cahill graduated from the Boston Latin School and returned to New York City to attend Manhattan College. Upon graduation, Cahill was accepted to Columbia University for an MA in comparative literature, but declined to enter the Army Language School in Monterey. He then took the Foreign Service Exam in 1956 and passed to begin his career in Foreign Service. He has also served in Oslo, Belgrade, Montevideo, Lagos, Colombo and Bombay. The interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on July 29, 1993.

HENRY A. CAHILL: “My main areas were German-Polish relations and Church-State affairs. The former brought me into contact with outstanding German officials. I must say that throughout my career the German Foreign Service has always shown top quality. Church-State affairs were important and exciting. Much of my time was spent gathering information. The regime did not like this. I ran a clandestine network that featured many people in strange places. The information flowed in. The secret police bounded after me. In one example, word came that the Organ School, the last musical school of the Church, was going to be raided and closed down. That was supposed to be top secret. The militia would do the task before anyone could defend or cry out, and then silence would descend. The info was relayed to Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. Within hours the word came back over the public airwaves: “The Polish government is about to forcibly close the last music school of the Catholic Church in Poland. There will be no more organists trained, no more sacred music published.” The authorities backed off and were furious. Our very good DCM Bud Sherer kept a running betting book giving odds on how soon I would be PNGed.”

Ambassador David J. Fischer was Rotation Officer in Warsaw (1964-1968). Born in Connecticut and raised in Minnesota, Ambassador Fisher was educated at Brown University, the University of Vienna, Austria and Harvard Law School. He joined the Foreign Service in 1961. His various assignments abroad took him to Germany, Poland, Sofia, Kathmandu, Dar es Salaam as well as to the Seychelles, where he served as US ambassador from 1982 to 1985. Assignments at the Department of State in Washington include those dealing with US relations with China, with Public Affairs and with Arms Control issues. He was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy and Robert Pasturing in 1998.

AMBASSADOR DAVID J. FISCHER: “In 1968, there was a major upheaval in the Communist Party, a lot of student riots going on, and only at that point did the students become really politically active, and we assisted them in every step of the way. We made sure they had access to mimeograph equipment, albeit on a very covert basis. We met with them and made sure their manifestos and messages were played back to Poland over Radio Free Europe. Then that became a very political struggle. In June 1968 all the student leaders were arrested. But it’s interesting because the leaders of that 1968 student movement, subsequently became the leaders of Solidarity and went on to become leaders in a non-communist Poland.”

Q: “You mentioned trying to help the students and all. How was the student uprising viewed at the beginning by the Embassy?

AMBASSADOR DAVID J. FISCHER: We certainly did not provoke the riots nor promote them. But we encouraged them, either directly with contacts with the leadership or through broadcasts from Radio Free Europe out of Munich. We knew all the leaders. They were young kids who had come to our houses with some regularity and asked what should we do? “Should we barricade the university? We know they’re going to bring in truckloads of armed militia, the para-militaries of the Communist Party. Should we attack them directly, should we give in.” It was a very open kind of a dialogue with us as individuals. We weren’t under instruction. On the one hand we certainly didn’t want these kids hurt, but on the other hand, anything which weakened the government was seen in our interest, I guess.”

A. Ross Johnson and R. Eugene Parta

Presentation to a seminar on “Communicating with the Islamic World,”

Annenberg Foundation Trust, Rancho Mirage, California, February 5, 2005

Jack Seymour was Poland Desk Officer in Washington DC (1977-1979). Mr. Seymour was born in the Philippines, the son of a U.S Navy family. He earned his bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth University in 1962. He joined the Foreign Service in 1967 after serving in the U.S Army for three years. His career included postings in Canada, Yugoslavia, Poland, Germany, and Belgium. Mr. Seymour was interviewed by Raymond Ewing on November 20th 2003.

Q: I have to ask you, as Polish desk officer, to what extent did you, were you involved in things Polish with the national security advisor of the period?

SEYMOUR: Ah, yes. That was very interesting experience, too.

Q: This is Zbigniew Brzezinski.

SEYMOUR: He was known as the real Polish desk officer. He really paid close attention to our relations with Poland, but most of my dealings at the NSC were with Bob King, who I believe now works for Tom Lantos in the House International Relations Committee.

Q: He was on the staff.

SEYMOUR: He was on the staff and he would say, well Zbig wants this or that, or Zbig wants to do it this way, and so on. We had a pretty good relationship, and something I remember well about President Carter’s visit is that Zbig was very keen that there be something with Cardinal Wyszyński. He wanted the president to meet with the Cardinal, the Primate, and Ambassador Davies was having a little trouble carrying that water because the Poles were resisting. He tried but reckoned they were adamant against it and did not think we should make an issue of it. I don’t know whether he felt it was a deal breaker or not but he did come in with a cable saying let’s work out an alternative. So what happened is that Rosalynn and Zbig went and met privately with Cardinal Wyszyński and I think that turned out fine.

Brzezinski was emphasizing a policy of promoting pluralism in Poland and other Eastern European countries and differentiating among them according to their diversity, pluralism and relative political independence or loosening of their ties with the Soviet Union and that they were implementing reform as best they could. This was our approach to Eastern Europe in general. And he wanted that meeting with Wyszyński to sort of play him up and emphasize the political diversity in Poland and that we regarded the Primate as an important representative of the people.

Zbig was also in close touch with the Polish American community; he was one of their heroes, especially after he had been appointed to direct the NSC. I had met him in Warsaw a couple of times and, of course, earlier in the State Department. I remember in particular a lunch with Jack Scanlan and Brzezinski and me. And to hear him talk in English was something (I had earlier heard him lecture in college, too), but he goes twice as fast in Polish, and a lot of it was in Polish. It was a very interesting lunch, but I had to strain to keep up with him.

Q: Because there were Poles there too.

SEYMOUR: Yes, I think there was one Polish intellectual leader there; I’m not absolutely sure—this was about 30 years ago! But that’s why so much of the conversation was in Polish.

Thinking who the Pole probably was there reminds me of another later incident involving Jack’s successor as political consular. Again, I won’t use his name but one could figure it out, I suppose. The story illustrates the close communication between the Polish-American community and their friends in Poland. I had been there a year or two years before this man came and replaced Jack, so I was pretty well grounded and had a number of contacts and new many of Jack’s. In those first weeks, I arranged a few lunches with some of them for my new boss and arranged one with a man named Stefan Kisielewski, one of the Catholic intellectuals of the older in generation, had once been in the parliament, wrote frequently for the Catholic weekly Tygodnik Powszechny, and was highly regarded in those circles. I believe he was the one at the lunch Jack Scanlan had for Brzezinski. Jack’s replacement had served in the FRG and I believe on the German desk, and “Kisiel”, as he was sometimes called after a pen name he used, also spoke German, but at that time I did not, or not very well. Anyway, they got going in German and about Germany because Kisiel had spent formative years there. And they got talking about Jan Novak, who had served many years as director of the Polish section of Radio Free Europe in Munich and later as President of the Polish American Congress

Q: Of the-?

SEYMOUR: Of the Polish Broadcasting for RFE (Radio Free Europe). And they got going because the political consular had apparently known Jan Nowak also from his days in Germany, and for some reason he mentioned something about Nowak’s having been a ‘Treuhandler,’ meaning a trustee for property, in this case for Jewish property, and in what could be taken as a negative way. Kisiel reacted testily and the conversation got rather loud, to the point where people at other tables were beginning to look around at them, which I tried to signal to my boss. Now, this was before I went to language school to get to a 3/3 in German and a posting in Bonn, and eventually a 4/4, so I did not follow the flow of the conversation that well, but got a sense of it. About a month later the DCM came running into my office waving a letter that had come, I believe, from Brzezinski or another prominent Polish-American citing the conversation and saying that Kisiel had been deeply distressed that the political consular held a negative attitude toward the chief of the Polish broadcast service for Radio Free Europe, etcetera, etcetera. And the DCM asked what I knew about this, because I was mentioned in the letter as being a “nice guy” but not in the conversation.

Q: Present but _______.

SEYMOUR: Present but not participating or following the conversation in German. So I of course told the DCM what I knew, and, as I recall, I was able to pull out a brief memo I had done to record some points Kisiel had made about Polish politics, which my boss would have seen as well. The DCM had to respond and he took my information and also conferred, of course, with my boss. The truth of it, as I saw things, was that my boss, in fact, seemed to hold Jan Nowak in high regard but had foolishly introduced the ‘Treuhandler’ business, which was probably based on rumor anyway, and that set off Mr. Kisielewski. That’s how I saw it and that’s how I recounted it to the DCM and later informed my boss.

That incident was really unfortunate. It showed the pitfalls of working in that environment, and it actually goes back to another Foreign Service insight. When I went about preparing to go out to Poland, studying the language at FSI, reading, and talking to people who knew Poland, everybody told me I should see Irene Jaffe. I don’t know if you know or remember; she was a long-time INR analyst and kind of a guru there and certainly for anything Polish. And so I duly went up and saw her and we had a good lunch or something and she told me about the politics and so on. She said she wanted to leave me with three bits of advice, and I hope I remember them all. The first one was try to understand, just try to understand what goes on in the life there and the politics. Second was never talk about one Pole to another Pole. And the third was to enjoy, because it’s a wonderful country with wonderful people and fascinating politics. But that second point is where my boss fell down, and I guess I should have been kicking him harder under the table because he simply fell afoul of that rule and the result proved its importance.”

Disclaimer: Ted Lipien, a former Voice of America Polish Service director and former VOA associate director, is one of the co-founders and supporters of BBG Watch.