By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Polish communist intelligence service and secret police spied on Voice of America’s (VOA) jazz expert Willis Conover during his visit to Poland in 1959 and tried to exploit it to influence U.S. diplomats into silencing Polish broadcasts of Radio Free Europe (RFE). As reported by Polish media, the spying on Conover is apparently documented in secret Polish communist police files stored at the Institute of National Remembrance.[ref]PAP and Polskie Radio 24.pl, “‘Gazeta Polska’: matka Rafała Trzaskowskiego była tajnym współpracownikiem bezpieki o pseudonimie Justyna,” September 5, 2018, https://polskieradio24.pl/5/3/Artykul/2186127,Gazeta-Polska-matka-Rafala-Trzaskowskiego-byla-tajnym-wspolpracownikiem-bezpieki-o-pseudonimie-Justyna.[/ref] Also mentioned in Polish media reports was a link to a larger spy scandal involving top U.S. diplomats in Warsaw in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Based on information in these media reports and on declassified U.S. government documents, as well as Radio Free Europe records, it can be argued that the spying and influence operation at the time of Conover’s visit had as one of its objectives to convince the U.S. administration to shut down RFE Polish broadcasts. In another indirect link to the Voice of America, a journalist participating in the spying operation targeting the American Embassy in Warsaw was a former VOA Polish editor who as a U.S. government employee of the Office of War Information (OWI) had produced content for VOA broadcasts in New York until 1944 and later returned to Poland.

Willis Conover played at one time a prominent role in promoting American music and cultural influence abroad through Voice of America broadcasts, especially during the early Stalinist period of the Cold War. The impact of his VOA jazz programs in Poland diminished as the communist regime lifted the earlier ban on modern Western music during the partial de-Stalinization period in the mid-1950s and never tried to ban or discourage it again, but he remained forever in the minds of many Poles who knew him a symbol of their cultural resistance to communism and socialist realism. He was enthusiastically greeted by jazz musicians and fans upon his arrival in Warsaw in 1959. To many Poles who heard his programs, he represented America and a hope for freedom. His programs had an even longer-lasting impact in the Soviet Union but in a somewhat different way.

A recent Voice of America video report described the significance of Conover’s influence on audiences in the Soviet Block countries although it is important to point out that his programs alone would not have had the same impact or the same mass following without VOA’s and particularly Radio Free Europe’s news and information programs. As important as his “VOA’s Jazz Hour” was, what really toppled communism was a popular movement of people who were primarily influenced by political programming of Western radios. With the exception of one expert, the VOA video produced more in a 1950s state television style than in the form of Willis Conover’s graceful program presentations, failed to reveal his true personality and to explain his role in the larger context of Voice of America’s foreign language broadcasts to countries behind the Iron Curtain.

VOA Video

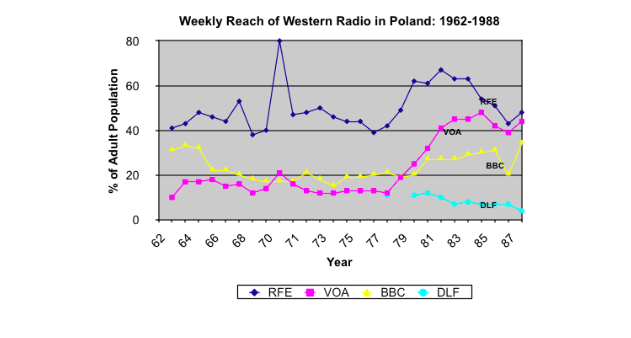

Nicholas Cull, historian and professor in the Master’s in Public Diplomacy program at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California, said in the Voice of America report that radio listeners in the Soviet Block “came to VOA for the jazz, and stayed for news.” I would say that it was more the other way. What radio listeners behind the Iron Curtain really wanted was the truth and a sign of support for the truth from the United States. The truth in news was ultimately much more important to most of them than music, which explains why for most of the Cold War, Radio Free Europe with its superior news programs and hard-hitting political commentaries had a vastly larger audience in countries like Poland, although not in the Soviet Union covered by RFE’s sister station Radio Liberty.[ref]

Former Voice of America director Geoffrey Cowan said in the VOA video that “jazz is an art form, but it’s not just a wonderful thing to listen to; it was something people could learn from without realizing they were learning from it.” In my opinion, as someone who grew up under communism in Poland listening to both RFE and VOA, Cowan’s observation is typical of what many well-meaning Americans believe, but it underestimates the intelligence and sophistication of foreign audiences living under dictatorships. In my experience, everyone who chose to become a listener to Western radios understood very well that their decision was a form of political protest and that jazz and rock & roll were ultimately of secondary importance but still served as powerful personal symbols and expressions of cultural opposition to communist totalitarianism. People who lived under communism in Poland did not need American jazz to teach them what freedom meant. What they needed was a reminder of America’s understanding and support for them in their struggle against communism. It was not jazz in itself but the fact that Americans brought jazz to them when it was discouraged and banned by their rulers. I did not know anyone in Poland who was attracted to VOA or RFE only by music, including jazz lovers and musicians although there may have been some.

One of the main features of totalitarian communism is that everything is political, including music. Maristella Feustle, Music Special Collections Librarian at UNT University Libraries in Denton, TX who curates the Willis Conover Collection may have presented a more accurate assessment of Willis Conover’s influence behind the Iron Curtain when she described his airing of a jazz recording sent to him in 1956 by Hungarian anti-communist freedom fighters. His programs were political at the time of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and Willis Conover knew it.

Some public diplomacy practitioners and former VOA officials tend to underestimate the core mission of the Voice of America during the Cold War and have neglected to focus their attention on hundreds of foreign journalists who carried out that mission. The Voice of America was extremely lucky that Willis Conover chose to work for them at a critical time of the Cold War, but the government-run station never recruited or developed a similarly talented and popular rock & roll DJ for its later programs, while Radio Free Europe Polish Service had a very popular music program in the 1960s “Rendezvous at 6:10” hosted by Jan Tyszkiewicz and Janusz Hewell who played the latest American and other Western songs. Janusz Hewell later worked for VOA’s Polish Service. Wojciech Żórniak was another popular VOA Polish Service music presenter. As the communist system in Poland began to unravel, Polish Radio started to rebroadcast one of Żórniak’s VOA music programs.

Whether he intended or not to be seen that way, for pro-Soviet regimes Willis Conover was a political figure who had to be banned when hardline communists still thought that they could suppress jazz during the early years of the Cold War, and when that became impossible, to be neutralized and possibly used to the regimes’ advantage in the new period of détente. Polish communists were less doctrinaire than their Soviet counterparts, but when it came to dealing with the United States and other Western countries, they used some of the same clandestine subversion, spying and propaganda tactics Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, an ex-KGB officer, still uses against the West.

New Polish media reports

An old Cold War East-West spy intrigue marginally involving the late Voice of America jazz connoisseur, impresario and DJ who became famous in Soviet Block countries for promoting American music, resurfaced in some conservative Polish media outlets during the recently concluded presidential election campaign in Poland but received little attention in the West. The mother of one of the Polish presidential candidates was identified in these media reports as the secret police informant who had spied on Conover during his 1959 visit to Poland. The information she reportedly provided to the secret police about Conover was a minor part of a much larger spying and influence operation directed against U.S. diplomats in which another Polish woman played a much more significant role–something that was not mentioned in Polish media reports. The other woman, in 1959 the wife of a high-ranking communist diplomat, was previously employed by the U.S. government and had worked as an editor of World War II-era Voice of America programs. Liberal Polish media was largely silent on this rather unsavory topic of Cold War espionage and sex scandals involving Polish female agents and American diplomats because they knew that it could hurt the chances of the liberal candidate for president. The Voice of America did not notice or chose not to notice these Polish media reports about communist secret police spying on its former famous jazz DJ.

Not being able to travel to Poland at this time, I did not have an opportunity to examine the communist secret police files, but Polish media reports provided me with some previously missing information that supported a few of my previous assumptions and conclusions about the communist regime’s war on Radio Free Europe. I waited until after the Polish presidential election to write my article with a mention of Polish media reports about secret police spying on Willis Conover to avoid any appearance of trying to influence the vote in Poland where I have not lived for many years and where I am not involved in any political activity. This is strictly my attempt to arrive at a better understanding of the history of U.S. international broadcasting.

A broader spy scandal

When Willis Conover visited Poland for the first time during the Cold War, the Voice of America was and still is today an international broadcaster managed directly by the U.S. government. In 1959, VOA operated under the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) which was the main public diplomacy arm of the U.S. State Department. I had worked for the Voice of America and its parent federal agency as an announcer, reporter, editor and manager from 1973 until 2006 when I retired from my last position as acting associate director. At the time of the spy scandals, Radio Free Europe was nominally outside of the federal government structure, but it was secretly funded and broadly overseen at that time by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

VOA and RFE programs were quite different during the Cold War. RFE broadcasts started 80 years ago in 1950 as a result of recognition by prominent private Americans and government officials that the Voice of America, being part of the U.S. government, could not do an adequate job of countering communist propaganda. Communist regimes were not happy with VOA, but they were much more fearful of Radio Free Europe. By the late 1950s, some regime officials in Poland were ready to tolerate the Voice of America, but they were not ready then or ever to accept RFE as an American-supported much more independent news organization with a specific mission to undermine their monopoly on information and power. Communist officials constantly demanded that the U.S. government withdraw its funding for RFE.

What is remarkable is that in Poland they managed to influence one U.S. Ambassador and another key U.S. diplomat to also demand that RFE broadcasts be terminated. Neither they nor these two U.S. diplomats realized that such a demand had no chance of being accepted in Washington. The opposition in the U.S. Congress, in both conservative and liberal media, and from the Polish-American community to such a demand doomed its chances of ever being approved by any administration that hoped to appeal at election time for support to Polish-American and other ethnic voters. In theory, however, Radio Free Europe could have ceased broadcasting, at least to Poland, had the Eisenhower administration been persuaded and chose to make such a decision.

Quite a few diplomats suffer from clientitis, a tendency to identify more with the interests of their host country rather than their own. It seems that at some point in the later 1950s and early 1960s, some U.S. diplomats in Warsaw allowed themselves to be persuaded that more “liberal” elements in the Polish Communist Party could weaken Poland’s forced alliance with the Soviet Union, liberalize the political system and move the country closer to the United States. These were all unreasonable assumptions because the communist regime in Poland was viewed by the bulk of the population as foreign-supported and illegitimate. There was no chance that Poland could evolve under the Communist Party rule to become a multi-party democracy with the Communists remaining in power and the Soviet Union respecting Poland’s sovereignty.

But as the communist regime in Poland decided in the late 1950s that a limited opening to the United States was desirable for its survival because without more food and consumer goods Polish workers were likely to continue their periodic strikes and protests, the U.S. Embassy had to be persuaded that liberalization in Poland was possible if only the Americans would withdraw their support for Radio Free Europe. Long before reports appeared in Polish media in 2018 and again this year about spying on Willis Conover, I have started to explore the idea that the communist regime in Poland had decided to allow him to visit the country in 1959 as part of a secret spying and influence operation directed primarily against American diplomats in Warsaw with the goal of limiting if not totally eliminating RFE broadcasts which were and would remain highly critical of the regime. Polish intelligence services apparently hoped to exploit Conover’s visit to convince the U.S. Ambassador to Poland Jacob Beam and the Embassy’s political officer Thomas Donovan that it was time to end Radio Free Europe broadcasts as being detrimental to improving U.S.-Polish relations by showing that there is a better alternative in the form of Voice of America’s less political and more cultural programs. Polish regime contacts of U.S. diplomats, which included female agents working for the communist intelligence service, presented them with a false alternative of better relations, more liberalization in the country for ordinary citizen and a greater opening to the West if they could convince Eisenhower administration officials in Washington to shut down or greatly restrain Radio Free Europe. By allowing Conover to visit Poland, the Polish regime signaled to the U.S. Embassy that they were not overly concerned about Voice of America broadcasts to Poland and even less about Conover’s jazz programs, but they were definitely unruffled by RFE Polish broadcasts and complained about them frequently and vociferously to U.S. diplomats in Warsaw.

If my assumptions are correct, Conover’s visit was to be seen by Americans as a sign of continuing liberalization of the communist government, which in fact was already becoming more repressive under First Secretary of the Communist Party Władysław Gomułka after the “thaw” following the 1956 workers’ protests. But even at that point, the regime in Poland believed that it could manage limited cultural exchanges with the U.S., such as Conover’s visit, or even expand them to its own advantage. The regime had a powerful control mechanism in place. The secret police in consultation with the Communist Party and government agencies decided who would get passports to travel abroad. They also used this power to intimidate and recruit informants.

With the help of female agents and informants, which apparently included the mother of one of today’s leading Polish politicians, the communist intelligence service appeared to have succeeded in influencing Ambassador Beam and Thomas Donovan to accept a deceptive argument that Radio Free Europe broadcasts were harmful to U.S. interests and were no longer needed. While it is possible that Beam and Donovan could have come to such an unusual conclusion entirely on their own without any outside influence, in reality this is not how things work in the real world. They were subjected to different forms of pressure and persuasion to accept the Polish regime’s view of Radio Free Europe. Allowing Willis Conover to visit Poland was most likely part of this effort although not the most important one. It would be hard to explain otherwise why Ambassador Beam and Thomas Donovan felt compelled to make such a strong case to Washington that RFE was a dangerous emigre operation that should be closed down. However, due to opposition from Radio Free Europe officials and journalists, the CIA and other members of the Eisenhower administration, RFE Polish broadcasts were neither terminated nor softened. Throughout this process, Willis Conover was probably unaware of the ultimate objectives of the Polish intelligence service although he was definitely aware of being spied on while visiting Poland ruled by a communist regime subservient to Soviet Russia. He most likely did not know who among the Poles informed on him to the secret police although some Poles would tell their Western friends that they had to give information about them to the authorities and would assure them that they would not say anything that could harm them.

It is difficult to imagine any other reason for communist authorities to unexpectedly grant Conover a visa despite his work for the Voice of America which they had condemned earlier as a subversive radio station if not to discredit and undermine political news reporting by Radio Free Europe. Technically, Conover was not a U.S. government employee of the Voice of America but worked for VOA as an independent contractor. Giving him a visa could have been an initial mistake on the part of the Polish Consulate in Washington, but this seems unlikely. The Polish authorities did not try to shorten his visit once he had arrived in Warsaw and in fact gave him some official publicity. Even state media covered briefly his visit, an indication that it was approved by the Communist Party and the government for a specific reason.

But while allowing Willis Conover to visit Poland and to meet with Polish jazz musicians and fans of his VOA programs, the regime’s secret police was also watching his every move. According to several Polish media reports going back to 2018, the person providing the Polish secret police with information about Conover’s meetings in Poland was Teresa Trzaskowska, the wife of Polish jazz musician Andrzej Trzaskowski. Conover and Trzaskowski became friends and he later visited the United States on a State Department grant. The alleged informant was further identified in Polish media reports as the late mother of Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski, who earlier this year one of the two leading candidates for president of Poland. In the second and final round of voting on July 12, 2020, Poland’s President Andrzej Duda, former member of the ruling conservative Law and Justice (PiS) Party, won by a small margin of votes against Trzaskowski, the candidate of the liberal Civic Platform (PO).

When told of the media reports about his mother already during his run for Mayor of Warsaw in 2018, Trzaskowski laughed them off as products of “PiS haters who bore into the past and go deep into family histories.” He was not even born when the spy scandal took place and can hardly be blamed for something that one of his parents did or did not do long before his birth. It is also important to remember that most Poles did not volunteer to spy for the secret police. They were usually blackmailed or had to be bribed into cooperating and gathering requested information. The regime had a total control over access to university education, better-paying jobs, scarce consumer goods, and foreign travel. It could withhold these benefits and also severely punish those who refused to cooperate. Secret police informants could still be anti-communists and some were known to deceive their handlers. Rafał Trzaskowski did not say back in 2018 or during the recent presidential election campaign that media reports about his mother, apparently based on documents preserved in the communist secret police archives, were fake news. Another point worth remembering is that no communist secret police records can be viewed as 100% accurate. Former President and Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa has said repeatedly that his secret police file was falsified by communist officials, but there would be no compelling or obvious reason to completely falsify files in an operation directed against the U.S. Embassy.

Since the alleged informant in this case has died, her side of the story will never be known. By refusing to cooperate with the secret police, she or her husband could be accused of spying for Americans or life could become much more difficult for them and their family. While Willis Conover was being watched by the communist secret police, he was also not the main target of the spying and influence seeking operation. The Polish communist intelligence service wanted to entrap U.S. diplomats. They also targeted U.S. Marines who served as security guards at the Embassy in Warsaw. One part of their operation was at least partially successful. Another U.S. diplomat serving in Warsaw, who had an affair with a female Polish agent, was blackmailed and passed secret documents to the Polish regime. He was tried for espionage in the United States, convicted and sent to prison.

By permitting U.S. diplomats to meet with various cultural opposition figures, encouraging their romantic liaisons with Polish women, and giving Willis Conover a visa to come to Poland in 1959, the communist authorities may have succeeded in persuading Ambassador Beam and Thomas Donovan that the regime was on its way toward liberalization. Both Ambassador Beam and Thomas Donovan suddenly became strong advocates for ending Polish broadcasts of Radio Free Europe which were much more critical of the Communist Party and its leaders than Voice of America programs from Washington. Ambassador Beam emerged as a particularly severe critic of RFE’s Polish Service and started to demand from Washington that it be closed down for doing damage to U.S. relations with the communist government in Poland. Ironically, one of the co-founders of Radio Free Europe was former U.S. Ambassador Arthur Bliss Lane who had served in Poland from 1945 to 1947 and resigned from the State Department to write a book about the takeover of the country by local Communists and their Soviet patrons through killings of political opponents and other massive repressions. Ambassador Bliss Lane was also highly critical of Voice of America broadcasts immediately after the war in the period before Willis Conover started his work for VOA.[ref]Former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane, who became a champion of creating Radio Free Europe and also advocated personnel and programming reforms at VOA, observed in 1948: “As for radio broadcasts beamed to Poland as the ‘Voice of America,’ my opinion of their value differed radically from that of the authors of the program in the Department of State. …I felt that the Department’s policy to tell the people in Eastern Europe what a wonderful democratic life we in the United States enjoy showed its complete lack of appreciation of their psychology. And, especially in Poland, which had suffered through six years of Nazi domination, it was indeed tactless, to say the least, to remind the Poles that we had democracy, which they also might again be enjoying, had we not acquiesced in their being sold down the river at Teheran and Yalta.” Arthur Bliss Lane, I Saw Poland Betrayed. (Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company), 1948, p. 219.[/ref]

Bliss Lane, Ronald Reagan and General Dwight D. Eisenhower were strong supporters of Radio Free Europe. Ambassador Bliss Lane also recommended in the late 1940s that VOA hire some of the new anti-communist Polish refugee journalists in the United States, including anti-Nazi fighter Zofia Korbońska, to replace fellow traveler pro-Soviet propagandists who were hired during World War II and supported the establishment of a Moscow-friendly socialist government in post-war Poland. World War II Voice of America was essentially a Soviet front organization. When American communist author Howard Fast was leaving his chief news writer and editor position at Voice of America in 1944 under pressure from the State Department and the Pentagon and getting ready to join the Communist Party and become editor of the party’s newspaper The Daily Worker, the second Voice of America director Louis G. Cowan, the father of the 22nd director, Geoffrey Cowan, gave him a glowing recommendation.

Radio Free Europe saved

Journalist Arch Puddington, former deputy director of the New York Bureau of Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty, wrote in his book about RFE history, Broadcasting Freedom: The Cold War Triumph of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, that “by the summer of 1959, the friction between the State Department and RFE reached the point where intervention by President Eisenhower and other high officials was necessary.”

Jacob Beam, U.S. ambassador to Poland, shared many of Thomas Donovan’s misgivings about RFE. On July 7, CBS reported that Beam had demanded the elimination of the Polish broadcasts, claiming they were too critical of Gomulka. Beam subsequently told the New York Times that RFE was airing blatant propaganda and included too many broadcasts in which conditions in Poland were placed in the worst possible light.[ref]Arch Puddington, Broadcasting Freedom: The Cold War Triumph of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2000), 123-124.[/ref]

Had the Eisenhower administration accepted Ambassador Beam’s recommendations that Radio Free Europe was no longer necessary for Poland, it would have been a major win for the communist regime in Warsaw which desperately wanted to silence RFE broadcasts.

Communist leaders were much less afraid of the Voice of America which at that time was managed by the U.S. Information Agency (USIA), a public diplomacy arm of the State Department. USIA Director George V. Allen declared in a memo to the president:

Even our best friends in Poland…think these broadcasts are carried out primarily in the interests of Polish refugees in New York.[ref]Ibid.[/ref]

It is possible that “our best friends” were Ambassador Beam’s friend Mira Michałowska, former VOA editor and wife of a communist diplomat, and Polish secret police informant “Justyna,” a friend of U.S. Embassy’s political officer Thomas Donovan. I cannot think of any pro-American democratic opposition figure in Poland during the Cold War who would have advocated the termination of Radio Free Europe Polish broadcasts and considered RFE broadcasts the voice of “refugees in New York.” It was a preposterous statement, but “Allen advocated outright elimination of the [RFE] Polish service, arguing that even major changes in the broadcast schedule would fail to convince officials in Warsaw that the station was not simply a ‘refugee outlet’.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref] The Voice of America, unlike Radio Free Europe, was part of Allen’s agency, the USIA.

Willis Conover’s successful visit to Poland was in early June. It was not, in my view, pure coincidence that a month later Ambassador Beam called for the elimination of Radio Free Europe Polish broadcasts.

Beam, Donovan and Allen apparently thought that VOA would be sufficient to keep the populations behind the Iron Curtain informed while USIA would expand cultural exchanges such as the successful visit to Poland by VOA’s Willis Conover. Their campaign to silence RFE’s Polish broadcasting proved to be ultimately unsuccessful. Journalist Arch Puddington wrote that Vice President Richard Nixon, who was greatly impressed by the enthusiastic reception he got on his visit to Warsaw in early August 1959 from ordinary Polish people who had learned about the route of his motorcade from Radio Free Europe Polish broadcasts, reportedly told Ambassador Beam to stop his anti-RFE campaign, explaining to him that it was also “an American diplomat’s responsibility to maintain a close relationship with the people.”[ref]Arch Puddington, Broadcasting Freedom: The Cold War Triumph of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2000) 125-126. Also see: Yale Richmond, “Nixon in Warsaw,” American Diplomacy, November 2010, http://americandiplomacy.web.unc.edu/2010/11/nixon-in-warsaw/.[/ref]

Arch Puddington also reported in his book that Thomas Donovan even objected to RFE’s accounts of prison conditions in Poland broadcast by recent refugees, but he ultimately “failed to convince RFE that change in its broadcasting policy was in order.” Polish media reports suggested that “Justyna,” the female informant who spied on Conover, was used mainly to spy on Donovan and spent a lot of time in his company, including driving through Warsaw in his embassy car. It took Richard Nixon’s intervention to put an end to the Polish regime’s anti-RFE intrigue.

A former VOA journalist working for Communists

The Cold War spy scandal in Warsaw had another interesting albeit indirect and past connection to VOA. A woman who became close to Ambassador Beam was journalist and writer Mira Złotowska Michałowska who during World War II had worked as a Voice of America Polish editor in New York, went back to communist-ruled Poland shortly after the war and married a high-ranking diplomat who later served as the regime’s ambassador to London and Washington. As a journalist and translator, Michałowska used about ten different pen names. Under her pen name Mira Michal she published soft pro-communist regime propaganda in American media—a pre-Internet attempt to influence Americans by obscuring the author’s origins and political affiliations. In the United States her articles were published in The Atlantic, Harper’s and other mainstream news and opinion magazines.

Mira Michałowska writing as Mira Michal, one of her many pen names, in the September 1962 issue of “The Atlantic“ magazine.

U.S. Embassy Warsaw spying scandal revealed by a Congressman

In an unsuccessful attempt in 1968 and 1968 to oppose Jacob Beam’s confirmation to become U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, Rep. John Rarick inserted into the Congressional Record various U.S. media articles about Ambassador Beam’s suspected liaison with journalist and former Voice of America World War II Polish editor Mira Michałowska. One of the articles cited by Rep. Rarick identified her as former wife of journalist and communist propagandist Stefan Arski. It is not clear whether Michałowska and Arski were ever married but both of them had worked for VOA or more precisely for the Office of War Information (OWI) which had VOA as one of its units. They both edited some VOA programs and produced pro-Soviet propaganda.

In 1947, Arski, whose real name was Artur Salman, lost his job at the State Department, where VOA was placed after the war. He was displaced by a U.S. citizen. He went back to Poland, joined the Communist Party and became one of the regime’s main anti-American propagandists renowned for his relentless attacks on Radio Free Europe and the bipartisan U.S. congressional investigation of the Katyń Forest massacre, the 1940 mass murder of thousands of Polish military officers by the Soviet NKVD secret police, which the Soviets and Arski falsely tried to blame on the Germans. Świat was one of several Polish regime publications edited by Arski. Michałowska produced only soft pro-regime propaganda and was in fact translating and promoting American literature in Poland, which may explain how she was able to become a close friend of the U.S. ambassador. She translated Hemingway but also books by her friend and former colleague Howard Fast who was Voice of America’s chief news writer and editor. He joined the Communist Party after leaving VOA in 1944 and in 1953 received the Stalin Peace Prize. He was a very popular American author in the Soviet Union and thanks to Michałowska he was also published in Poland. Citing U.S. media reports in a speech in the House of Representatives on February 8, 1968. Rep. John Rarick exposed Ambassador Beam’s “friendship” with Michałowska who at that time was the wife of the Polish communist ambassador to the United States.

The present Mme. Michalowskl has reportedly been an agent of the Soviet and later Polish Communist Party Central Committee since 1936. As wife of the important Michalowski, who had been in London at the same time Beam was stationed there, she leads a very busy life and is now being glamorized as a Washington hostess. Her life In Warsaw was described in the book “Poland Little Known” as follows:

“. . . Roving everywhere Is Maria Zientarowa known also as Stefan Wilcosz [Wilkosz] or Michalina Wilkoszowa or Tadeusz Makowski or Jan Michalskl or Stefan Welczar, former friend of comrade Kliszko, former wife of Arski, the Editor-in-Chief of ‘Swiat’ when he was an employee of OWI, and at present the wife of the Director of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Jerz [Jerzy] Michalowski. . .”

Myra [Mira], through her “friendship” with Ambassador Beam, was able to get Informa tion which she fed back to her Soviet bosses. It Is now presumed that the high ranking Polish intelligence officer who was supplying the United States with valuable security In formation from Warsaw was forced to seek refuge in the United States because of her. She is also credited with arranging the Scarbeck Case to take the heat off the Im portant real agents, with Beam himself supplying the Information to Dikeos who reportedly broke the case.

Edith Kermlt Roosevelt In her column. Between the Lines, discusses Mme. Michalowski and states:

“The various marriages of a Warsaw charmer may provide the incentive that could force the issue of Communist espionage and policy manipulation into the limelight. . . . White House and State Department circles have remained silent. They have confided that they fear the revelations could spark a new wave of McCarthyism in the United States.”[ref]114 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 114, Part 3 (February 8, 1968 to February 22, 1968), p. 2861.[/ref]

Ambassador Beam eventually broke off his relationship, whatever it was, with Mrs. Michałowska and put the sex-spy scandal behind him. He was named U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union and eventually became a strong supporter of Radio Free Europe, serving as chairman of the RFE board.

However, as Jacob Beam was being proposed to become U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union in the late 1960s, conservative members of the U.S. Congress unsuccessfully opposed his nomination on account of the sex and spying scandal during his ambassadorial assignment in Warsaw.

Sensational details of the spy scandal were reported by the Washington, D.C. Evening Star on March 9, 1969 in an article by James Kilpatrick titled “Jacob Beam: Our Man in Moscow,” inserted in The Congressional Record on March 11, 1969 by Rep. John R. Rarick.

The story of those Warsaw days [1959-1961] is as fantastic as any tale ever contrived by Ian Fleming and his fictional James Bond. To judge from various printed hearings and other published material, Communist intelligence agents infiltrated Beam’s embassy as merrily as a swarm of termites boring holes in a tasty log.

Irvin C. Scarbeck, second officer of the embassy, was among those who succumbed to the age-old lure of a beautiful woman. He fell in love with a 22-year-old blonde, Ursula Discner. The presumption is strong that she was an agent of Polish intelligence. In any even, Ursula set him up for a raid that led to blackmail; this led in turn to the theft of classified documents. Scarbeck was caught, indicted, convicted and sentenced at first to 30 years in prison. Later the sentence was reduced. It was a sensational case.

Scarbeck was not alone in female involvements. A detachment of Marine guards, assigned to the embassy, engaged in wholesale revels with Polish girls. The wife of a middle-rank embassy employee had an affair with a Russian agent, A code clerk implicated in an illicit relationship was “permitted to resign.”

Another Foreign Service Officer, Thomas A. Donovan, was also named during the hearings of the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee as having had sexual relations with Polish female intelligence agents.[ref]James Kilpatrick, “Our Man in Moscow,” Evening Star, March 8, 1969 as quoted by Rep. John R. Rarick in Congressional Record, March 11, 1969, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1969-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1969-pt5-3-3.pdf.[/ref]

Leopold Tyrmand

While spying on Donovan, the Polish security services also received information on Conover’s meetings with jazz musicians and other Poles during his 1959 visit to Poland. According to Polish media reports, the agent recruited by the Polish intelligence service under the code name “Justyna” provided information on both Donovan and Conover and was reported to be close to Donovan, not Conover. She also reportedly gave the communist secret police information on Polish dissident writer and also a jazz enthusiast Leopold Tyrmand who later emigrated to the United States and became a leading intellectual of American conservatism at the Rockford Institute.

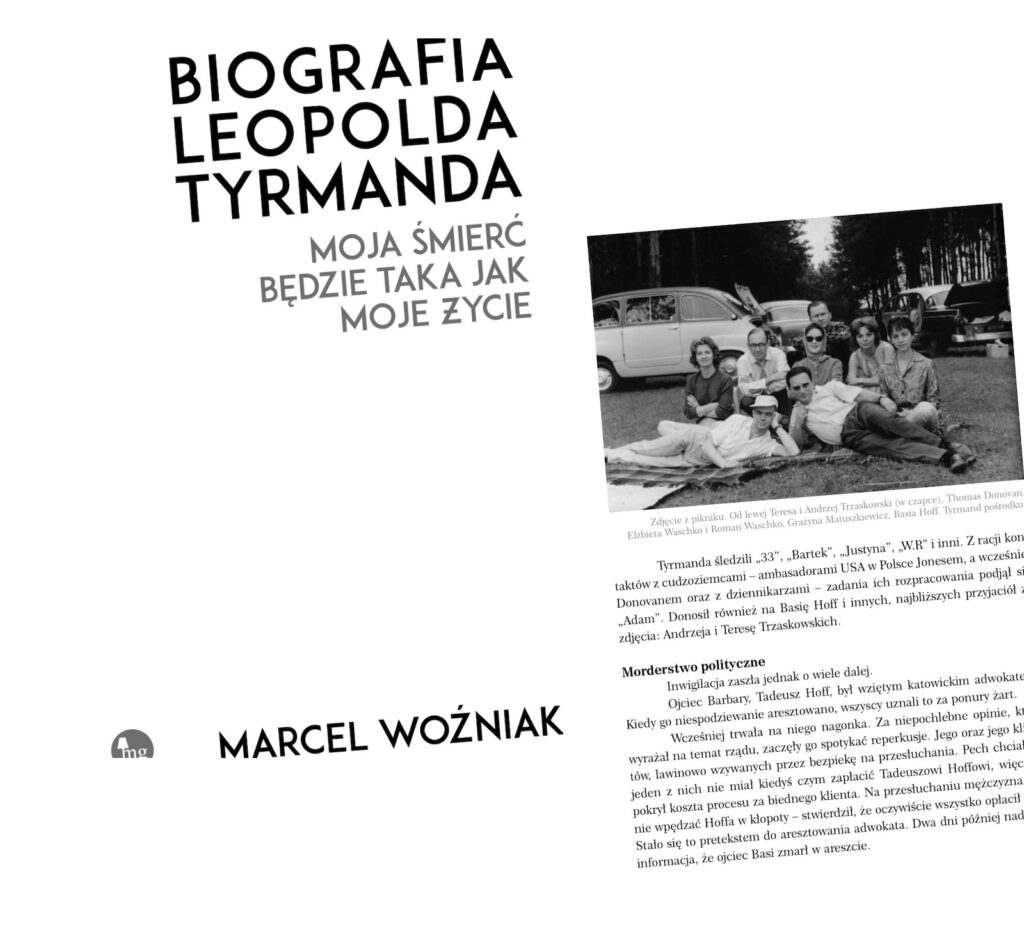

Leopold Tyrmand’s son, Polish-American columnist Matthew Tyrmand, sent me a copy of a biography of his father recently published in Poland. The author, Marcel Woźniak, refers to the spying scandal and mentions secret police agent “Justyna” without identifying who she was. He also mentions Teresa and Andrzej Trzaskowski and suggests that they were also being informed on to the secret police by another agent. It was normal for the communist secret police in Poland to spy on its informants using other informants. The book has a photo showing Tyrmand, Teresa and Andrzej Trzaskowski and U.S. diplomatThomas Donovan. According to his biographer, Tyrmand, who played a key role in popularizing jazz and Conover’s programs in Poland in the 1950s, was spied on by several informants. He was frequently threatened by the secret police. Tyrmand’s father-in-law, a well-know lawyer Tadeusz Hoff, was arrested in 1962 and suddenly died in prison. The family suspected that he was murdered because of his public criticism of the regime and perhaps also as a warning to his son-in-law . The circumstances of his death were never successfully investigated.

Conover knew about spying

Many years later when I was in charge of the Voice of America Polish Service during the communist regime-imposed martial law in Poland in the 1980s, Willis Conover told me that he thought that Polish secret police agents were spying on him even in the United States and may have tried to get access to his VOA office. At the time I thought he was exaggerating, but in retrospect he might have been right. He had all of his mail delivered to a post office box and picked it up himself to be sure that no one would know with whom he was in contact in Poland and in other countries in the communist block.

When visiting Poland in 1959 Willis Conover knew that he would be a target for spying by the secret police. He and I did not discuss details of his 1959 trip to Poland, but he was convinced many years later that the communist intelligence service was still interested in his contacts with opposition and cultural figures in Poland and among Polish exiles in the West. It was a reasonable assumption. Knowing him as I did, there is no doubt in my mind that as far as U.S. diplomats and USIA officials were concerned, he had no part in their plan to shut down Radio Free Europe. His friends in Poland would have been absolutely opposed to it and so would he. USIA Director Allen’s claim that America’s friends in Poland did not think much of Radio Free Europe Polish service was a pure fiction most likely thought up by the regime’s intelligence and secret police operatives and fed by them to U.S. diplomats in Warsaw.

Conover-VOA-RFE-U.S. Embassy Warsaw

Willis Conover’s 1959 visit to Poland appears to have been used by the Polish intelligence service without his knowledge as part of an unsuccessful operation to shut down the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe. U.S. Ambassador to Poland Jacob Beam and political officer Thomas Donovan also appeared to have used Conover’s visit to boost their ultimately failed arguments in favor of silencing Polish broadcasts of Radio Free Europe as no longer necessary and harmful. U.S. diplomats might have thought that Voice of America broadcasts, including Conover’s jazz programs, and USIA-sponsored exchanges with Poland, were more than enough to bring Western news, culture and ideas to the Poles. Their Polish government contacts, including secret police and intelligence agents, would have certainly tried to convince them that more visits by VOA personalities like Conover, more visits by VOA correspondents and more cultural and academic exchanges between Poland and America would follow if the U.S. government muzzled Radio Free Europe.

Both Ambassador Beam and Thomas Donovan were, however, profoundly mistaken in their analysis of the Polish situation. By the early 1960s, jazz had lost its forbidden fruit flavor in Poland. American music was no longer banned, but free speech, free media, free travel abroad for everyone, non-communist controlled political parties and labor unions, and free elections were still unattainable. Communist authorities allowed Western music to be played by Polish Radio as part of their own propaganda campaign to gather support and help them weaken opposition to the regime. By the 1960s, regime officials in Warsaw would have been happy if Voice of America and Radio Free Europe broadcast nothing but Western jazz and rock & roll.

Cultural exchanges between Poland and the United States continued to expand in the later period of the Cold War supported and managed by the United States Information Agency and the State Department. While benefitting some regime officials and supporters, they also had an overall beneficial effect for those Poles who never ceased their principled opposition to communism and Soviet domination. U.S. Embassy officials insisted that at least some known opponents of the communist regime be included in these exchanges. Regime official had to agree in order to be able to benefit themselves from these programs.

None of these activities, however, were enough on their own to help the majority of Poles become informed about what was happening in Poland and abroad and how they could go about demanding that the regime respect their human rights. The Poles continued to rely for getting uncensored news on Radio Free Europe and increasingly on the Voice of America after the Reagan administration lifted previous political censorship restrictions on VOA. Willis Conover and I made a decision during the martial law in Poland in the 1980s to resume his jazz programs with Polish translations. We did it largely for symbolic reasons and because we had airtime to fill thanks to the expansion of our programs to Poland by the Reagan administration. It was at that time that Willis Conover told me that he believed he was being spied on by someone connected with the Polish Embassy in Washington.

Conover’s legacy and conclusions

While we knew that our news broadcasts and telephone interviews with opposition activists were much more important during the Solidarity period in Poland and that our other music programs for young listeners in the 1980s were more popular than any jazz program could possibly be, this does not negate the fact that Willis Conover had a considerable intellectual influence in the early 1950s on a group of young Poles opposed to the communist regime when the authorities still banned jazz and other forms of modern Western music. After 1956, regime propagandists realized that such music bans were counterproductive. As they were lifted and musical tastes changed, Conover’s programs no longer had the same strong impact, but he remained an important figure to many Poles who still remembered him. They valued and honored him as an American icon of cultural resistance to communism. I know from our friendship that Willis Conover detested Communists and supporters of all totalitarian ideologies and also feared them, but he generally tried to keep his jazz programs free from politics while realizing that he was still making a powerful political statement in communist-ruled nations. Making his programs overly political would have turned them into propaganda, make them less appealing, and he would not have been able to receive visas to visit countries in the Soviet Block.

Former Voice of America Russian Service editor Irene Kelner described best what Willis Conover’s jazz programs meant to listeners in the Soviet Union where cultural censorship under communism lasted much longer than in Poland.

Listening to Willis Conover jazz program was a breath of fresh air, air of freedom. He and his programs introduced many people behind the Iron Curtain to the other way of life and helped them become regular Voice of America listeners. I first listened to a Willis Conover program in 1956 in Moscow when I was only 12-years-old. His programs and later Voice of America content changed my views and 18 years later made me emigrate from the USSR to the USA.

He made the right choices at the right time for his type of programming. Not to take anything away from Conover’s contributions and legacy, RFE and VOA political programs were not less important than his jazz programs; they were vastly more important, and they were essential in countries living under communism, especially Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty broadcasts.

By the end of the 1950s, communist leaders in Poland accepted the idea of carrying out limited and carefully managed economic, cultural and academic exchanges with the West but only if such interactions could help them keep their hold on power. They miscalculated to some degree the risks for the regime from such exchanges and the ability of even friendly American diplomats to silence Radio Free Europe. While U.S. cultural diplomacy programs helped to encourage intellectual resistance to communism, they would not have worked without news, information and hard-hitting commentaries provided mainly by Radio Free Europe and to some degree by the Voice of America to a broad audience which included not only intellectuals but also millions of industrial workers, farmers, middle class professionals and their children.

Voice of America’s famous jazz DJ Willis Conover did not succumb to the communist secret police influence and propaganda operation—if anything spying on him made him more anti-communist—but, incredibly, highly-educated and experienced American diplomats did fall for the charm of female agents and empty promises of liberalization of the Communist Party and the Gomułka regime—the same regime which less then ten years later started a major antisemitic campaign and forced many Polish Jews to emigrate during the 1968 Polish political crisis. Thanks to the intervention of President Eisenhower, Vice President Nixon, Polish American leaders and members of Congress, the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe was saved, but it came very close to being silenced in 1959 by efforts of communist agents and propagandists who managed to dupe a few impressionable American diplomats. Let it be a lesson for anyone who minimizes the threat of propaganda and disinformation today from Russia, China, Iran, Cuba and other countries trying to undermine American democracy.

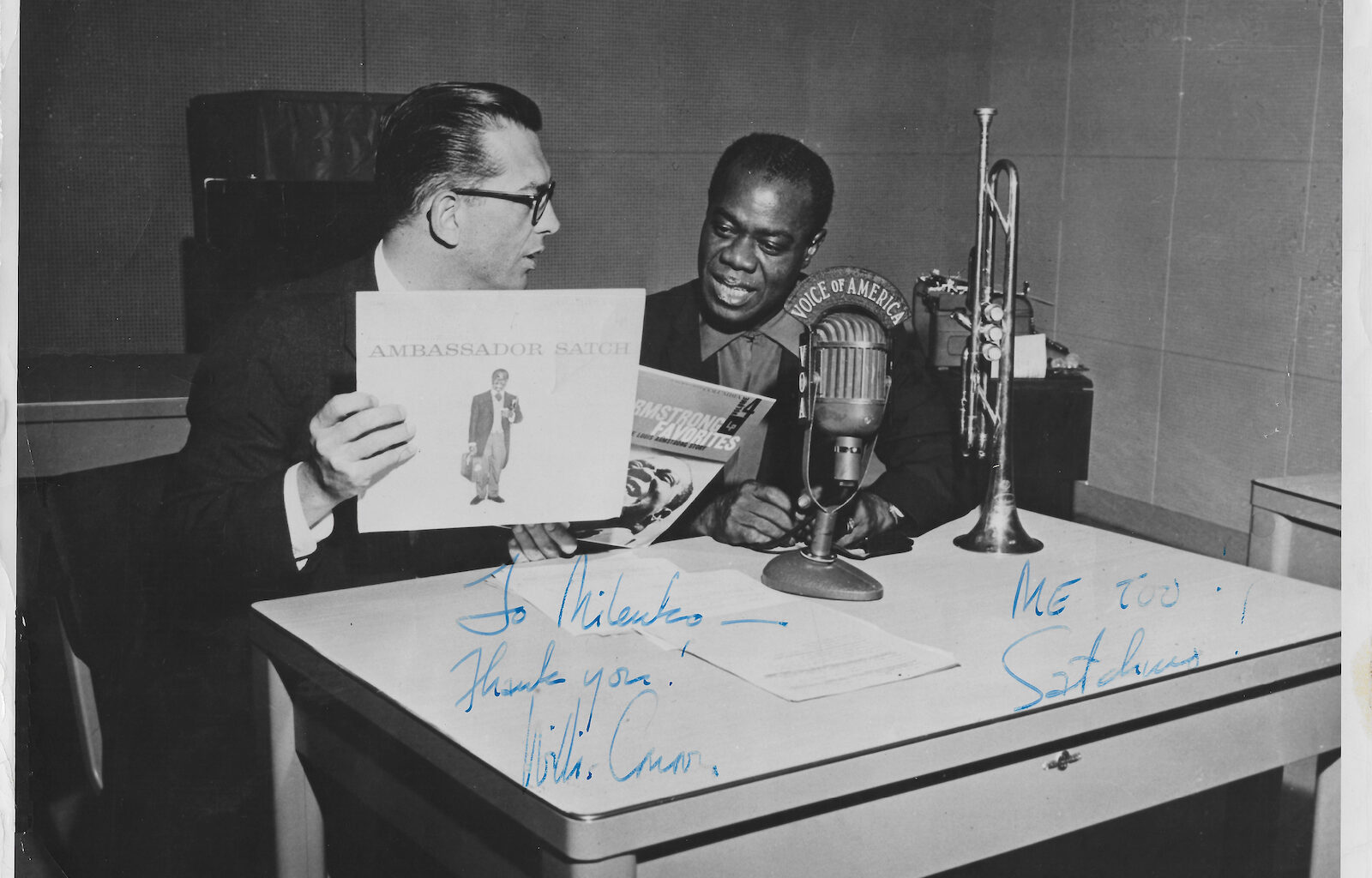

Photo Credit: According to Maristella Feustle of The University of North Texas (UNT) in Denton, TX, the photograph of Willis Conover (December 18, 1920 – May 17, 1996), the late host of the Voice of America English Service program, Music U.S.A., with jazz musician Louis Armstrong, was probably taken at the VOA studio in Washington, D.C. on July 13, 1956. The album “Ambassador Satch” was released in May of 1956, and Conover did a five-hour interview with Louis Armstrong on July 13. Ms. Feustle, Music Special Collections Librarian at UNT University Libraries who curates the Willis Conover Collection, helped to determine that the inscription from both Willis and Satchmo was to Croatian composer and orchestra conductor Miljenko Prohaska (17 September 1925 – 29 May 2014). Willis Conover dedicated two of his regular programs to Prohaska and his music.

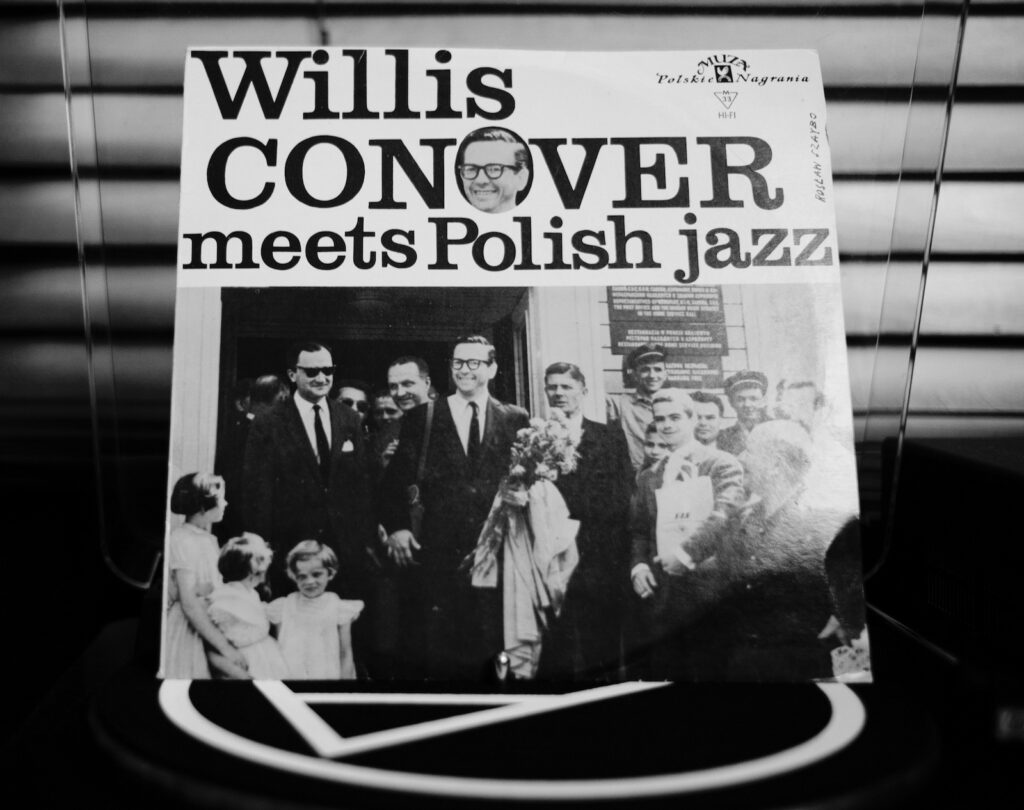

WILLIS CONOVER meets Polish Jazz Muza Polskie Nagrania album cover by Rosław Szaybo. Cover Photo: Marek A. Karewicz.

1 comment

Willis Conover’s “VOA Jazz Program” was an effective demonstration of American “soft power” during the Cold War. The Polish Communist regime may have thought that allowing Conover to visit Warsaw in 1959 would somehow support its campaign against Radio Free Europe. In advocating ending RFE broadcasts to Poland, Ambassador Jacob Beam and First Secretary Thomas Donovan may have succumbed to “localitis.” But they followed a State Department and USIA policy formulated prior to their tour in Warsaw aimed at curtailing RFE at the expense of VOA. Undersecretary of State Robert Murphy and other State officials contended on March 2, 1957, that “the delicate situation in Poland did require reconsideration” of RFE Polish broadcasts. That policy was part bureaucratic offensive and part reflection of overoptimistic assumptions about Party leader Gomulka’s October 1956 reforms (a view shared by CIA analysts). I provide details in “Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty; the CIA Years and Beyond” (Stanford UP, 2010) and have posted relevant declassified U.S. State Department and CIA documents in the Wilson Center Digital Archive e-Dossier 32.

Comments are closed.