BBG Watch Commentary

INTRODUCTION: A young and successful Russian investigative reporter Anastasia Kirilenko is one of many who believe that the United States lacks a strategy for responding to Putin’s propaganda war. After being dismissed last year by the previous management of Radio Liberty’s Russian Service, even her name could not be used in new Radio Liberty Russian programs despite her impressive work to uncover the Kremlin’s corruption secrets. Earlier in her reporting for RFE/RL, Anastasia Kirilenko interviewed Marina Salye, a Russian politician who in 1992 headed a special commission in St. Petersburg that investigated Vladimir Putin, then chairman of the city’s Foreign Relations Committee, and accused him of corruption. It was one of Radio Liberty’s major journalistic accomplishments. Now shunned by RL, Kirilenko is being published in the West and even by some of the more independent media in Russia. Her colleague, Kristina Gorelik, a highly respected human rights reporter, was also fired by Radio Liberty despite being a target of vicious anti-Semitic online attacks by Russian ultra-nationalists.

Experts like former BBG member and former Radio Liberty director S. Enders Wimbush accuse the American management of RFE/RL and BBG of lacking both strategy and vigilance since the BBG was founded in 1999. Mr. Wimbush told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the BBG response to Putin’s aggression in Ukraine has been “feeble.”

It was not always like that before the new federal agency took over. As the U.S. First Lady, Hillary Clinton praised Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. “For four decades, Radio Free Europe unmasked the lies and deceit of dictatorship by broadcasting information about the world beyond the Iron Curtain and spreading a message of freedom, democracy, human rights, and the rule of law,” she said in 1996 at the RFE/RL headquarters in Prague, Czech Republic. In 2013, as Secretary of State and after she became an ex officio member of the Broadcasting Board of Governors, she called the BBG “practically defunct” and unable to engage in the war of ideas. “So, we’re abdicating the ideological arena, and we need to get back into it,” Mrs. Clinton said. Members of Congress of both parties want to enact major reforms through the H.R. 2323 bill designed to restructure U.S. international media outreach.

UPDATE: While Anastasia Kirilenko is still unwelcome at Radio Liberty, and Kristina Gorelik, still has no job, since last week the Russian Service has a new director in Prague, the Czech Republic, where RFE/RL has its headquarters. Since September 2015, the Broadcasting Board of Governors has new CEO and director who has made some personnel changes in Washington. RFE/RL, however, still has no permanent president, and BBG has no strategy for responding to Putin propaganda, Anastasia Kirilenko told BBG Watch. But perhaps as a sign of new BBG CEO John Lansing’s growing managerial influence, VOA Russian Service recently interviewed Anastasia Kirilenko while she was being ignored by Radio Liberty. The new director of RL Russian Service since last week is experienced journalist Andrei Shary.

In a wide-ranging online conversation Anastasia Kirilenko describes how, in her view, Radio Liberty lost its way.

CONVERSATION WITH FORMER RADIO LIBERTY INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER ANASTASIA KIRILENKO – PART I

A Putin Corruption Reporter Too Radical For Radio Liberty

CONVERSATION WITH FORMER RADIO LIBERTY INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER ANASTASIA KIRILENKO – PART II

No Particular Radio Liberty Management Support For Interview With Putin’s Accuser

CONVERSATION WITH FORMER RADIO LIBERTY INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER ANASTASIA KIRILENKO – PART III

Life in Post-Soviet Russia of Former Radio Liberty Reporter

QUESTION: Were were you born and what was it like growing up in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: I was born in a village in Altay region in Southern Siberia, but I grew up in Novossibirsk, a university and scientific center in the southwestern part of Siberia. Novosibirsk means “New City of Siberia” in Russian. With a population of about 1.5 million, it is the third largest Russian city and the most populous one in Asian Russia. It became a major industrial center along the Trans-Siberian Railway, and it is sometimes called the “Chicago of Siberia.” Novosibirsk also had its own mafia.

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: I was born in a village in Altay region in Southern Siberia, but I grew up in Novossibirsk, a university and scientific center in the southwestern part of Siberia. Novosibirsk means “New City of Siberia” in Russian. With a population of about 1.5 million, it is the third largest Russian city and the most populous one in Asian Russia. It became a major industrial center along the Trans-Siberian Railway, and it is sometimes called the “Chicago of Siberia.” Novosibirsk also had its own mafia.

As I was growing up, the city had a gangsters’ district where I lived, which may explain my later interest in reporting on corruption and crime. My family was, or rather became, very poor. In 1992, like many adults, my parents were not receiving their salaries for several months during the market reforms in Russia. My father was, and still is, an engineer in a factory producing railroad track rails, but at that time he had to work as an occasional taxi driver to feed our family. This ended when his car was seized by his passengers who happened to be gangsters.

On my road to my elementary school, there were burned-out kiosks, a sign of gangster activity to punish those who refused to pay protection money. May be once a week, we saw funerals of members of the local mafia. Even teenagers participated in “strelkas”, the gun battles between different groups of gangsters. It was frightening for someone as young as I was. Drugs were sold in front of our school. When our teachers asked the policemen to take action, they said they could do nothing because it would be “difficult to prove in court.” In front of our dilapidated house, a policeman built a new home for himself.

A Novosibirsk pantry. Photo courtesy of A. Kirilenko.

Food was difficult to get. I still remember a kind of “steak” made from porridge, using oil in our kitchen from humanitarian aid containers stamped “USA,” and other survival-type products which our neighbors also had to rely on. We were raising a few chickens to have something to eat. One time in the winter, my father drove to a small village to buy some feed for our chickens and did not return for many hours. When he finally showed up late at night, he had frostbitten hands. He told us his car had gotten stuck in the snow with one one around to help him. I realized that he could have died that night. That’s how the life in Novossibirsk was when I was only eight years old in 1992.

QUESTION: Who inspired you the most when you were a child and a teenager: your parents, your teachers, somebody else, or were you always somewhat independent-minded?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: Like many people of their generation, my parents were confused by what was happening in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union. When I turned 16 and wanted to do something else with my life, they tried to discourage me from studying foreign languages. Fortunately, I was determined and disobeyed them. I started on Italian first, then Japanese. This may now sound funny, especially to Americans, but my grandmother wanted me to work in a cafeteria, so I would have direct access to food and would never go hungry. The spirit of the Soviet times continued well into the 1990s.

My inherent inspiration was non-conformity. The reality of life around me was not inspiring. Nobody I knew was studying Italian, so I decided that I would. Our school teachers were also confused. They would say that having good grades was not important for a future career. They urged us instead to develop “good contacts” and told us that without knowing someone important, we’d be losers in Russia.

QUESTION: Were you told anything in school about communism, Lenin, and Stalin?

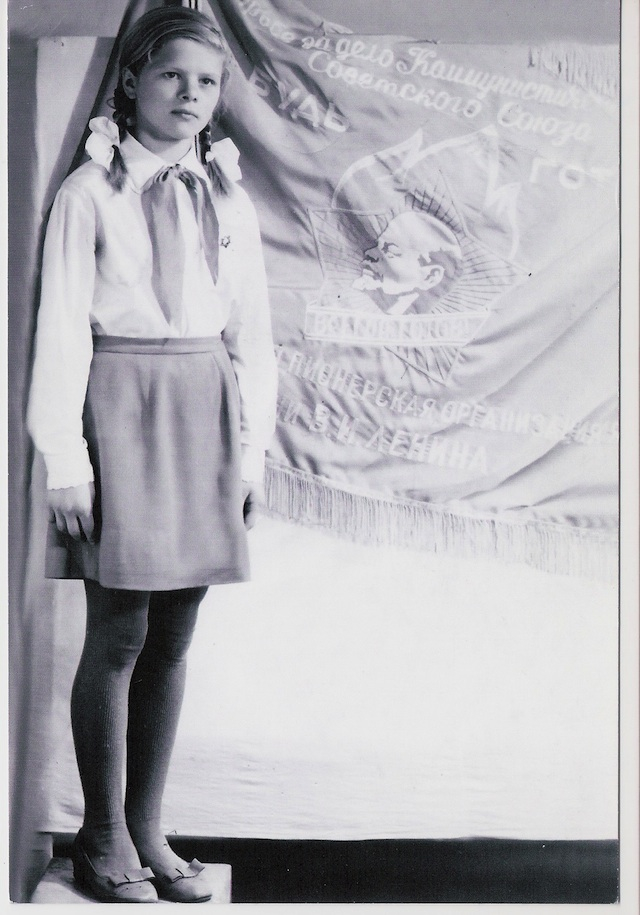

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: I went to an elementary school in my gangsters’ district near our home because my parents had no money to send me to a different school somewhere else. I learned everything about Lenin because back then, in 1990, when I started school at the age of 6, the Soviet Union still existed. A picture of Lenin and the words of the Soviet anthem were on the first pages of our school textbook for teaching the alphabet. When the USSR collapsed, there were no new schoolbooks available for free distribution to children for several years. When I was even younger, may be four or five, I remember that a huge portrait of Lenin hung on the wall in my kindergarden. I had to wear a white dress and to go to one of the Lenin statues in the city, there were plenty of them everywhere, and bring flowers on Lenin’s birthday, April 22nd. That’s why I don’t judge those ordinary people who grew up and were educated under the Soviet system too severely. What critical opinion of Lenin can a four-year-old have? My mother, for example, always had excellent grades at school and at the university, but she never questioned the Soviet system.

QUESTION: What were your dreams for the future when you went to college?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: When I went to college, I dreamed of becoming a scientist because I was good in physics and mathematics, and my teachers encouraged me to go in that direction. As a child, I conducted some chemical and other scientific experiments at home on my own. But as I discovered later, scientists at the Siberian Branch of the Academy of Science in Novosibirsk became one of the poorest category of workers in Russia. I remember reading about a scientist who was forced to look in the trash for things he could use or sell. Others were forced to emigrate. So I decided that in order to survive, I would continue studying foreign languages. I did translations at night to earn some money and during the day I went to lectures at the university. I graduated with a degree in international relations from the Novosibirsk State University of Economics and Management.

QUESTION: Were your university studies already free from Soviet or other propaganda?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: Some propaganda was still imposed on us. We were told, for example, that Russia had done everything to be accepted by the West, but the West rejected us. Nevertheless, my curriculum included some basic subjects not tainted by propaganda, and in my case, also foreign languages: German, French, and Japanese. University education was free for those who qualified through entrance exams. I was accepted into a Master’s degree program in French and journalism and studied both in Moscow and in Paris.

QUESTION: How did your parents react to what was happening in Russia in the 1990s?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: My parents believed that the United States destroyed the USSR. Fortunately, I was close to my brother, and we both knew a different version of events from what was taught to us in school. Our outlook was more or less liberal and we both rebelled against parental authority. I began to see things differently. Even during the Soviet era, my mother would tell us that she had nothing to do at her state job. I still remember her joking about knitting at work. This was common in the Soviet period and even in the early 1990s. When the USSR still existed, some state employees even took outside courses during office hours in making advanced macrame knots. They did not ask themselves if the communist economy and low worker productivity in the Soviet Union were not a major problem which led to the system’s collapse. Since my teenage years, I began to wonder how was it possible to knit at work and be convinced that this was also the fault of the United States?

QUESTION: Did you learn anything in school about the millions of Russians and other Soviet citizens who died in the Gulag labor camps or were executed on Stalin’s orders?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: As I recall, we were told almost nothing at school about Stalin’s repressions. Nothing negative, but nothing positive either. When I quoted from a book I found in an outside library outside that Stalin’s era was marked by “the escalation of violence,” a teacher ordered me to be quiet. In our literature class, we learned about the famous poetry of Osip Mandelstam who died after being sentenced to a camp in Siberia, but nobody told us that it had anything to do with Stalin or that the reason for Mandelstam’s arrest and death was his powerful, non-conformist poetry.

QUESTION: Did you or anybody in your family listen to Western radio stations?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: My parents didn’t listen to any–not BBC, not Radio Liberty; and I didn’t know then of their existence. Later, when they learned I was working at Radio Liberty, they said it is a “subversive station,” but by then they were partly joking. I remember them reading books by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn because suddenly he became a mainstream writer in the early 1990s. Without questioning life in the USSR, they were later happy about the new flag of Russia, about the election of Boris Yeltsin–because such attitudes also became mainstream. I also remember that in the early 1990s, Russian media carried only positive reports about the United States, President Bill Clinton laughing during a meeting with Russian students.

QUESTION: What has changed?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: In my opinion, the Russian government, as I know now from my own research, was not at all interested in stamping out the infamous Soviet-style political and economic corruption. On the contrary. So, when the U.S. government proposed to the Russian officials that they would help them find the missing money of the Soviet Communist Party, positive reports about the U.S. in Russian media gradually disappeared.

QUESTION: How did your parents react to what was happening in the 1990s?

Anastasia Kirilenko’s mother, Natalia Kirilenko, as a young girl in 1970s. Photo courtesy of A. Kirilenko.

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: The harshness of survival in the 1990s, nepotism, obvious corruption, great discrepancies in wealth, in what was officially called “democracy,” quickly disappointed my parents. I can’t judge them harshly when I think about everything that happened to them during that period. For example, when I was nine, my brother and I made brass knuckles from a piece of lead we found in the trash. My mom asked us to give them to her so she could protect herself in case she were attacked on the way from work. At that time, anybody could be robbed, a woman raped, a fur cap stolen when the temperatures were at minus 22 degrees Fahrenheit. So, the 1990s, the time of my childhood, were a huge shock for many Russians, not just for my parents. These conditions, I think, have been underestimated and poorly understood in the West. They still have profound consequences for today’s Russians.

Svetlana Alexievich, the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature winner from Belarus, describes what happened in her book “Secondhand Time: An Oral History of the Fall of the Soviet Union,” as does American journalist David Satter in his book “Darkness at Dawn: the Rise of the Russian Criminal State.” It still pains me to read these books.

QUESTION: Before you started to travel abroad, did you have any non-Russian friends?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: While at the university, I was enrolled in French and German foreign language centers in Novosibirsk where native speakers, foreigners, thought. Studying foreign languages, we discussed various subjects, including LGBT rights, which would have been impossible to discuss elsewhere. Learning new languages was not only about acquiring a new language proficiency, but also about extending our horizons on political questions. I also had an Italian pen pal, and a Chinese friend. Some people in the Russian Federation are also like “foreigners” to native Russians even though they are Russian citizens. For example, I was friends with a Teleut student at the university. His father was a real Siberian shaman. I was attracted by diversity since my childhood.

QUESTION: Did you know any Americans? What were your early opinions about the United States?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: I had only a negative and somewhat snobbish opinion about American food. But that changed when I traveled to the U.S. from France and was served ten different types of oysters in a restaurant in Georgetown, in Washington, DC. While there are exceptions, I admire the Americans for the respect they have for every person regardless of that person’s origin, and for the opportunity America offers to those who want to be self-made, also regardless of ethnic origin or social standing. That’s the famous “American Dream”. The article like the one I saw in Time magazine several years ago, which was titled “We are Americans, Just Not Legally,” is unimaginable even in Europe.

As for the anti-corruption measures, the United States is sometimes much more committed to them then Europe. Some Russian friends of President Putin are not allowed on the U.S. territory due to their criminal links, while a bank in France would gladly give money to a Russian tycoon if he is a friend of Putin’s friend. Despite the sanctions, Putin’s proxies feel well treated, especially in France. I can see that while there are problems in America, there is more sincerity in the American commitment to human values than in other countries. It’s obvious to me that these values allowed America to prosper.

QUESTION: Do you think some Americans are naive in their views of President Putin?

ANASTASIA KIRILENKO: Americans have been sometimes naive about the activities of first, Soviet, and now Russian government intelligence services in the United States. I talked about it with former KGB general Oleg Kalugin. The Russian government profits from the freedom of speech in America. RT (formerly Russia Today) opened a bureau in Washington to spread fake news and lies. As I recall, in the UK, RT has been issued already two warnings. There is also the first official complaint in Germany against such so-called Russian government “media.” An American tradition of non-conformity propels many U.S. citizens to dislike their government, and sometimes even some intelligent Americans seek out RT and agree to be interviewed. That makes me sad. In that case, why not start watching North Korean TV?

Radio Liberty Gave No Support To Investigative Reporters

INTERVIEW WITH FORMER RADIO LIBERTY INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER ANASTASIA KIRILENKO – PART IV

Kevin Klose, then RFE/RL president, with Radio Liberty Russian Service journalists in 2013. Photo courtesy of Radio Liberty-in-Exile.